At the end of August, the US Energy Information Administration reported that it had been overstating domestic demand for oil and energy products to a considerable degree. Using imprecise and lagging data, the calculations for the amount of product being exported overseas was understated by an average of 16%. That meant more output was being used elsewhere, thus less product being used here. While that is a positive for US producers being able to ship wherever they can, it was a more savage reflection on the economy especially this year.

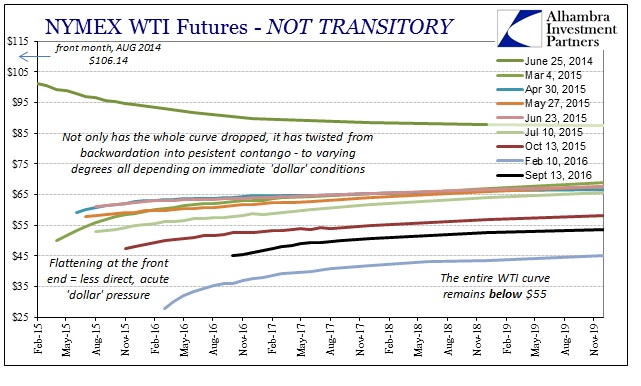

In other words, nothing terribly surprising in oil unless you are expecting dramatic improvement for the US economy through something like a “full employment” liftoff. Instead, viewing oil as a primary intersection between finance and economy, the “rising dollar” part of the eurodollar decay unsurprisingly remains as an ongoing process – not a cycle to be moved into and then quickly out of. All the same mechanisms that were shocking economists in late 2014 and early 2015 are still visible here in the summer of 2016. It’s not going to just go away; like oil and gas inventory, it only gets worse a little more each time in these uneven waves.

Today it was the influential International Energy Agency’s (IEA) turn to deliver more such bad news. When oil prices first crashed starting in late 2014 and really January 2015, commentary was filled with the words “supply glut.” Particularly related to US fracking as the biggest contribution to non-OPEC growth, the intent in using those words almost exclusively was to downplay the possible negative implications of a serious commodity crash (especially what was causing it) given that such crashes are monetary by nature. At most, there would be some words expressed about economic “concerns”, but for the most part oil prices were purported to be the victim of too much success.

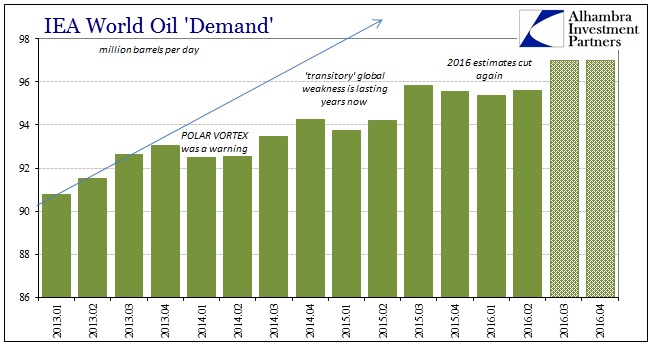

A year and a half later, supply remains a problem but focus has finally shifted toward demand, though not by choice. And it is here that the IEA’s latest forecasts have hit oil views hard. First, OECD oil inventories continue to climb, hitting a new record of 3.11 billion barrels in July even though, “refinery activities reached a summer peak, crude oil inventories refused to decline.” Now, however, refineries are starting to reject additional crude supplies, forcing the IEA to reduce its 2016 forecast for coming refinery runs to the “lowest rate in a decade.”

The biggest problem related to the “supply glut” is that nowhere are there signs of economic recovery. Instead, demand continues to be well-off pace especially given where it “should” have been by this point. From the IEA report:

The result has been a slump in oil demand growth from a robust 1.4 mb/d in the second quarter to a two-year low of 0.8mb/d in the third. Even with a modest weather-related uptick forecast for the end of the year, oil demand growth in 2016 will struggle to get above 1.3mb/d. Refiners are clearly losing their appetite for more crude oil. During the fourth quarter, they are expected to process only 0.1 mb/d more crude than a year ago.

Our latest numbers provide some clues as to why. Recent pillars of demand growth China and India are wobbling. After more than a year with oil hovering around $50/bbl, the stimulus from cheaper fuel is fading. Economic worries in developing countries havent [SIC] helped either. Unexpected gains in Europe have vanished, while momentum in the US has slowed dramatically.

As a result, the IEA doesn’t expect oil supply and demand to balance now until the end of next year – and that just means oil inventory, already at records, will continue to grow until then. As the press release notes, given prices and inventories we should be seeing supply falling off sharply while demand rises strongly in reaction to prices. Instead, the IEA finds the opposite condition where supply continues to grow while demand doesn’t react at all to the reduced price and only continues to slow further despite two years of it already.

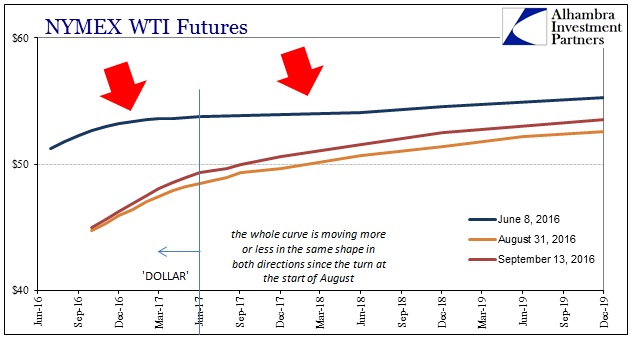

Oil prices were, as you would expect, down sharply today given these estimates and trends. As I wrote before, the clue to all of it is in the front end of the oil futures curve, where the “dollar” acts as the intersection of economy and finance. Basic economics teaches us that when the price of something falls significantly the demand for it should rise, ceteris paribus. That’s the problem with economics as there is no such thing as “all else equal.” In terms of oil prices, it’s as if there is “something” holding back the world’s economy from taking advantage of these fundamental conditions as a truly strong (or even just normal) economy would.

The world’s crude output is going into storage because there is no economic growth, just as there hasn’t been for years. That isn’t recession; it is monetary all the way through. That is why viewing the oil price crash appropriately in the eurodollar context would have meant helpfully skipping the ridiculous idea of “transitory”, and what that meant(s) for everything beyond oil.