HARRISBURG, Pa. — Facing a shortfall of more than $50 billion in his state’s pensions, and with no simple solution at hand, Gov. Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania is proposing to issue $3 billion in bonds, despite the role that such bonds have already played in the fiscal woes of other places.

And he is not alone. Several states and municipalities are considering similar action as they struggle with ballooning pension costs.

Interest in so-called pension obligation bonds is expected to intensify in the wake of a recent Illinois Supreme Court decision that rejected the state’s attempt to overhaul its severely depleted pension system. The court ruled unanimously that Illinois could not legally cut its public workers’ retirement benefits to lower costs, forcing lawmakers to scramble for the billions of dollars it will take to keep the system intact.

While the Illinois ruling is not binding on other states, analysts think it may influence lawmakers elsewhere to look to alternatives to cutting public pensions. The Illinois justices offered a list of all the times since 1917 that state lawmakers had ignored expert warnings and diverted pension money to other projects. They said, in effect, that the lawmakers had to restore the money.

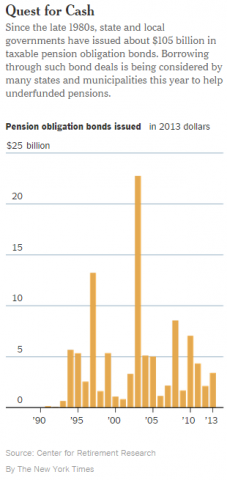

Quest for Cash

Since the late 1980s, state and local governments have issued about $105 billion in taxable pension obligation bonds. Borrowing through such bond deals is being considered by many states and municipalities this year to help underfunded pensions.

Pennsylvania and other states and cities fear similar restrictions.

Pennsylvania and other states and cities fear similar restrictions.

“My reaction was, ‘Yeah, that’s going to play here,’ “ said John D. McGinnis, a lawmaker in Pennsylvania, which has also been diverting money from its pension system, setting the stage for a crisis as more and more public workers retire. The state has no explicit constitutional mandate to protect public pensions, as Illinois does, but that is irrelevant, said Mr. McGinnis, a Republican and former finance professor at Pennsylvania State University.

“The judiciary in Pennsylvania has been solidly of the belief that there are ‘implicit contracts,’ and you can’t deviate from them,” he said. If lawmakers in Harrisburg were to unilaterally cut pensions now, he said, they could be taken to court and be dealt a stinging rebuke, like their counterparts in Illinois.

Against that backdrop, pension obligation bonds may appear tempting, even though such deals have contributed to financial crises in Detroit, Puerto Rico, Illinois and other places.

The deals are generally pitched to state and local officials as an arbitrage play: The government will issue the bonds; the pension system will invest the proceeds; and the investments will earn more, on average, than the interest rate on the bonds. The projected spread between the two rates makes it look as if the government has refinanced its pension shortfall at a lower interest rate, saving vast sums of money.

But that’s just on paper. In reality, the investment-return assumption is just that — an assumption, and a deceptive one at that because it does not take risk into account.

Fiscal analysts say it is possible, in theory, to shape a pension obligation bond deal responsibly, but that is not what they usually see.

Instead, the deals are typically used to make troubled pension systems seem a little less troubled for a few years, allowing elected officials to celebrate a pension reform without having to make the system sustainable over the long term.

The flood of cash from the bonds may also tempt officials into taking a break from their pension-funding schedule — the very action that has caused so much pension distress to begin with. Skipping annual pension contributions produces an off-balance-sheet debt that can start growing exponentially.

“These deals are being done as a budget gimmick,” said Matt Fabian, a managing director at Municipal Market Advisors, who keeps a database of municipal bond defaults and other mishaps. “They should not be done at all.”

But that has not stopped officials from pursuing them. Kansas recently authorized a $1 billion pension obligation bond and is seeking an underwriter. Alaska has been mulling the idea, although the governor, Bill Walker, opposes it. Hamden, Conn., recently borrowed $125 million for pensions, and the Atlanta school district wants to borrow up to $400 million to revive a dwindling pension plan for bus drivers and cafeteria workers.

In California, Orange County recently borrowed $340 million for pensions; South Lake Tahoe borrowed $12 million; and Riverside and Pasadena each took out new pension obligation bonds to refinance their old ones.

Municipalities are borrowing for their pension funds even in Michigan, where local governments are said to carry the stigma of Detroit, which dealt steep losses to its bondholders in bankruptcy. How a state handles the distress of one city is seen by credit analysts as the implicit policy for all municipalities in that state.

After declaring bankruptcy in 2013, Detroit sought to have $1.4 billion of pension obligation bonds voided outright, saying they had been sold illegally in 2005 and were not enforceable. Ultimately, Detroit settled the debt for about 13 cents on the dollar, the lowest recovery rate of any of its bonds.

Michigan now takes extra precautions with pension obligation bonds, requiring local governments to be rated at least Double-A and to close their pension plans to new employees before borrowing. That has not thwarted Ottawa County, Saginaw County and Bloomfield Hills.

And outside Michigan, San Bernardino, Calif., has told its bankruptcy judge that it wants to settle its pension obligation bonds for just a penny on the dollar.

Investors evidently see the risk as acceptable, but it is still there. The governments typically invest the proceeds aggressively in their efforts to capture the widest spread. But success is more elusive than it looks in the presentations to officials.

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College tracked a sample of 270 pension obligation bonds issued since 1992 and found that governments were borrowing in the wake of market run-ups, investing when asset prices were high, and reaping losses in subsequent corrections.

The center also found that the greater a government’s fiscal problems, the likelier it was to attempt the arbitrage play.

“Those least able to absorb the risk were most likely to do so,” said Jean-Pierre Aubry, the center’s assistant director of state and local research.

There are signs that at least some state and local officials are taking such findings to heart. In Kentucky, a plan to borrow $3.3 billion for the state-run teachers’ pension fund fizzled in March. In Colorado, a plan to borrow up to $10 billion was derailed by three Republican senators just before the legislative session adjourned.

But in Pennsylvania, Governor Wolf, a Democrat elected last year, sees the risk as acceptable. Five years ago, the state enacted what it called a pension reform that set up a new, cheaper pension plan for the public workers hired from 2011 onward; everyone in the existing plan continued to accrue the richer benefits. In the heat of the election campaign, Mr. Wolf called for giving the plan more time to work.

Indeed, a reform affecting only future employees will take decades to achieve appreciable savings because it will take decades for the current public workers to complete their careers, retire and be replaced by new workers with the cheaper benefits.

Pension obligation bonds look appealing as a stopgap measure. They are, in fact, illegal in Pennsylvania, but proponents say that is not a problem because the statute can be amended.

The idea has bipartisan support. Last year, a Republican state representative, Glen Grell, called for borrowing $9 billion for pensions, saying it “would save $15 billion over 30 years.” His proposal mustered considerable support, but then Mr. Grell resigned to become executive director of the state pension plan for public-school employees.

Barry Shutt, a retired state worker, has been staging a one-man vigil against pension obligation bonds at the state capitol in Harrisburg. He had a sign that said: “Borrowing money is not a fix. It kicks the can down the road and steals from our children and grandchildren.”

Mr. Shutt is a retired accountant who began his career as a state auditor and later administered food programs. He said there was little doubt as to when and why the state pension system went off the rails: In 2001, lawmakers increased everybody’s pensions retroactively, causing a huge, wholly unfunded increase in the state’s obligations.

The lawmakers figured that booming stock-market returns would pay for the costly increase, a mistake made by officials in many other states and cities as well. Two stock crashes later, the mistake is apparent, but it is too late to reverse the increase — it is deemed it an “implicit contract” that cannot be breached.

Pension obligation bonds would only make the problem worse, Mr. Shutt said. “When you’re borrowing money for pensions,” he said, “you’re getting a new credit card to pay off the old one, and you still haven’t paid off the old one.”

Source: Borrowing to Replenish Depleted Pensions – NYTimes.com