By James Mackintosh

Bonds are meant to be safe, dull investments. But there is nothing boring, and not a lot of safety, in Japanese government bonds this year: The 40-year has returned an extraordinary 48% in six months, including the paltry coupon, and other long-dated JGBs have also had their best returns on record. U.K. and German long-dated bonds have produced similar returns to those after the collapse of Lehman.

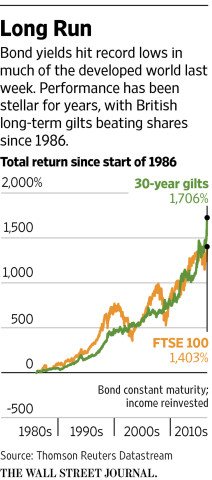

Returns on U.S. Treasurys are less exotic, but the 30-year has returned 22% this year—a gain big enough to worry longtime bond watchers.

It would have been easy to make the mistake of thinking the bull run in bonds was over many times since then-Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker got it started by taking control of inflation. The bet that the Japanese bond market—which long had the lowest yields in the world—would finally buckle has lost so much money for so many people that it is known as the “widowmaker” among traders.

That hasn’t stopped Eric Lonergan, who runs a multistrategy fund for M&G in London. He has 15% of his fund betting against long-dated JGBs, and has endured a brutal move in the market against him in the past few weeks. Yet, he believes the likelihood is that the market will soon turn.

And yet generations of traders have been saying the same thing. And they have been wrong.

Neil Dwayne, global strategist at Allianz Global Investors, is still buying. “Every piece of analysis we do on the bond market tells us they are structurally overvalued,” he said. But he is buying Treasurys anyway. “That’s what you have to do when you have the ludicrous valuations in Europe and Japan.”

It isn’t only the sudden ramp-up in prices (and so fall in yields) that is worrisome. Bonds have been reacting to economic news in strange ways, and their relationship to equities has, at least in part, broken down.

There are two reasons today why this can’t continue.

Reversing the 35-year trend is most likely to be driven by governments loosening the purse strings. Central bankers have been urging such fiscal stimulus as they worry that their own monetary tools are having damaging side effects, hurting banks and risking share- and property-price bubbles.

The U.K. has scrapped its balanced-budget target since the Brexit vote, while France, Italy and Spain are pushing back against European austerity rules. Japan ditched its planned sales-tax increase earlier this year, and, in a reversal of norms, the tightest fiscal policy on offer in the U.S. election comes from the presumed Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton, not the Republican, Donald Trump. Elites in developed countries are also being forced to discuss the concerns of working-class voters, which would be most easily addressed by handouts or job-creation programs.

“It feels as though the helicopters are coming, but they’re not coming very quickly,” said Sebastian Lyon, chief executive of London’s Troy Asset Management, in a reference to “helicopter money” printed by central banks to finance government spending. He has long worried about deflation, but expects it to be replaced with inflation once governments are scared enough to act.

It is dangerous to try to time the end of a bubble, as prices can always get even more disconnected from reality. Sometimes it really is different this time, too. But investors thinking of buying bonds at record-low yields should worry both about short-term excess and a long-term change in politics.

Write to James Mackintosh at James.Mackintosh@wsj.com