By Tyler Durden at ZeroHedge

The Fed may have officially tapered QE at the end of 2014 but that doesn’t mean it is done buying Treasuries: since the Fed never ended rolling over maturing paper, it means that it will remain indefinitely active in the open market. And while there were no sizable maturities from the Fed’s various QEs to date (only $474 million in 2014 and $3.5 billion in 2015) that will change dramatically this year, when Brian Sack’s team will have to purchase about $216 billion to replace matured TSYs. According to JPM calculations, this represents half the net new government debt that will be issued over the next 12 months.

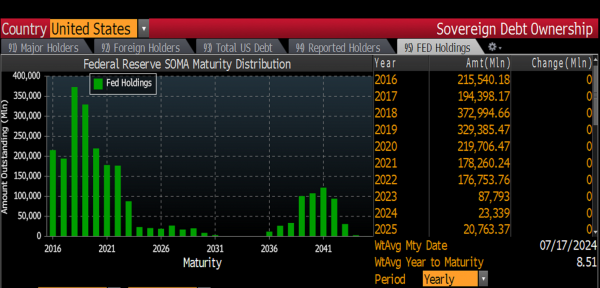

The amounts rise from there: $194 billion comes due in 2017, about $373 billion in 2018 and $329 billion in 2019 for a grand total of $1.1 trillion over the next four years as shown in the following Bloomberg chart:

The Fed’s intervention in the Treasury market is well known: here is a brief Bloomberg summary of where we’ve been and where we are going:

The Fed is the biggest holder of the government’s debt. Its $2.5 trillion hoard, amassed in a bid to support the economy after the financial crisis, is more of a focus for some investors than the trajectory of interest rates. From this month through 2019, about $1.1 trillion of Treasuries in the portfolio are set to mature.

Even though the Fed’s holdings of Treasurys won’t rise and remain flat at about $2.5 trillion, the Fed’s reinvestment mandate means a return to active POMO which also means that there will remain a backstop net buyer for 1 of every 2 bonds issued by the US government.

Clearly this is bullish for bond bulls (one can stop wondering why year after year Goldman is so bearish on TSYs every year with its 3.00% yield target and is so eager to buy everything its clients have to sell) for whom “the Fed’s signals that it will roll over the obligations have been another reason to doubt the consensus forecast that yields will rise in 2016. If officials had chosen to stop funneling that money into new debt, the government would likely have to boost borrowing in the market by roughly an equivalent amount this year, potentially pushing up Treasury yields.”

Hypotheticals aside, the Fed’s indirect monetization of debt has led to the Fed being the owner of about 30% of all 10-Year equivalents currently, further leading to dramatic notional scarcities among CUSIPs that were most actively purchased by the open markets desk, usually in the form of Off The Run paper, which meant that the Fed has far less On The Turn to lend to Treasury shorts in repo, leading to major “special” prints in the repo market manifesting by near-fail, or -3.00%, levels when one wishes to borrow any given Treasury.

However, as Bloomberg explains, as the Fed will rolls over maturing Treasuries, it will add new On The Run issues to its balance sheet. Since Operation Twist, the Fed has had less of those sought-after securities to lend out in a daily program it has to ease shortages in the market. As a result, these Treasuries have frequently commanded a premium in the repo market — leading more trades to go uncompleted, or ‘fail,’ in bond parlance.

If the Fed’s stock of those Treasuries grows, the central bank should be better able to alleviate the shortages through its SOMA Securities Lending program, said Joseph Abate, a money-market strategist in New York at Barclays Plc, a primary dealer.It will become “easier for people to access the securities they need to cover any shorts in the on-the-runs and, correspondingly, the level of fails should fall,” Abate said. “The more difficult it is to cover a short, the less liquidity there is in the market.”

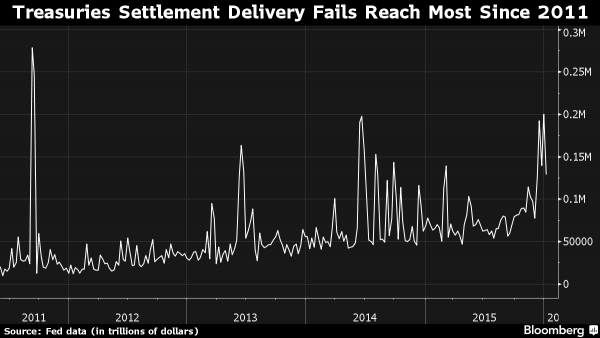

Dealers say bond trading has become more difficult as regulator-imposed risk limits make it costlier for banks to transact in all types of debt. While Treasuries remain one of the most liquid global markets, failing trades rose this month to about 2.5 percent of average daily volume, from about 1 percent before Twist, according to Barclays. The dollar amount of uncompleted Treasuries trades reached the highest since 2011 last month, Fed data show.

The topic of soaring repo “fails” was covered recently, and is shown in the chart below: a direct function of the Fed’s encroachment in the open market.

Then there is the question of remitting interest payments back to the Treasury, about as close to directly funding the US government as it gets (with the exception of course of the Fed directly paying $19 billion to fund the Highway Bill: that was undisputed direct funding of the US government by the banks that make up the Federal Reserve system). According to Bloomberg, if the Fed had opted not to reinvest this year, the Treasury would have had to make up for the lost funding with additional debt sales that might have boosted 10-year yields by 0.08-0.12 percentage point, according to Priya Misra at TD Securities LLC.

One wonders just how much more debt the Treasury will have to issue and how much higher yields will go up by if the Fed ever does unwind its balance sheet?

It also leads to another question: why did the Fed decide to begin the “normalization” process by hiking rates first instead of first removing the truly unorthodox support for asset classes, namely unwinding its balance sheet, or at least stopping the reinvestment of maturing bonds. The answer: because the Fed’s rate hike is a farce, further compounded by the fact that the Fed Funds rate on December 31, the only day it actually matters for bank balance sheet purposes, was well below the Fed’s 25bps floor.

But that’s a topic for another post.

For now, we leave it to Mark MacQueen, co-founder of Sage Advisory Services Ltd., which manages $12 billion in Austin, Texas, to explain precisely why those who are long assets could care less about nominal rate hikes but are terrified of the Fed’s actual balance sheet unwind: “The Fed tightening gave us little worry, but the unwind of the balance sheet gives us major worries. The Fed is keenly aware that the balance sheet has a much greater impact on the overall yield levels in the markets going forward than raising rates.”

And there’s your answer why the Fed is hiking instead of winding down its gargantuan $4.5 trillion balance sheet: it might actually achieve the intended effect.