The focus on China and the Chinese economy is not just related to its size but more so the fact that it is the pivot point for the whole global system. In pure economic terms, as “end demand” from the developed world economies slows, the Chinese economy either absorbs that reduction (through its own internal “stimulus”) or passes it on to the resource economies further down the global supply chain. There is a similar process that works out in terms of the financial relations to these economic transitions, though these funding differences have very real implications that don’t seem to be incorporated into analysis of China.

For example, we can see clearly the “dollar’s” influence on China financing via the PBOC’s Total Social Financing (TSF) statistics. The entire idea of TSF is to estimate the financing “needs” of the real economy and how these needs are being met. The largest segment is internal bank loans (in RMB) which accounted for about two-thirds (stock) of the total in March 2016. Entrusted loans were 8%; trust loans 3.9%; corporate bonds 11%; and equity financing 3.3%. The remaining “needs” are related to forex and external trade: foreign currency loans made up 1.9% and undiscounted bankers acceptances the remaining 3.9%. It is the latter two that have been shrinking and sharply so since the middle of 2014.

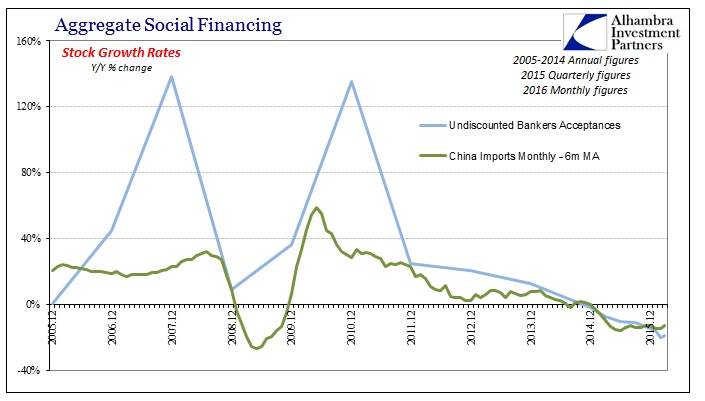

Bankers acceptances are upfront deposits that are used to fund foreign trade (I covered the mechanics of acceptances here). If you wish to import some foreign goods, you then need that foreign currency which can be deposited in whole or in part, turned into an acceptance which then can be used as payment to the foreign agent in exchange for goods shipments. Thus, the governing factors in acceptance volume are trade and the availability of upfront currency. With the dollar the world’s trade denomination, the financial factor in Chinese acceptances is really eurodollars and the ever-present “dollar short.”

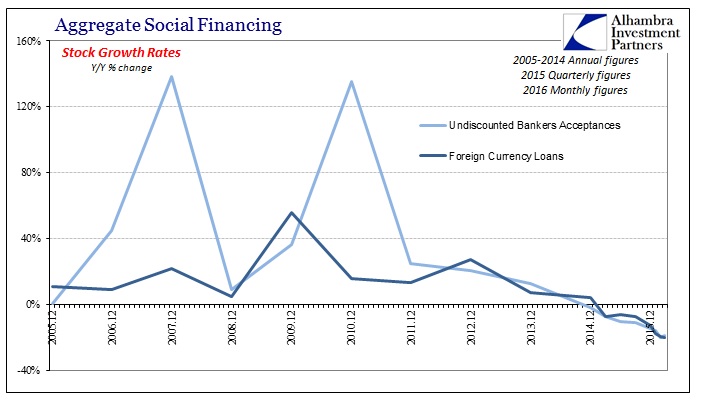

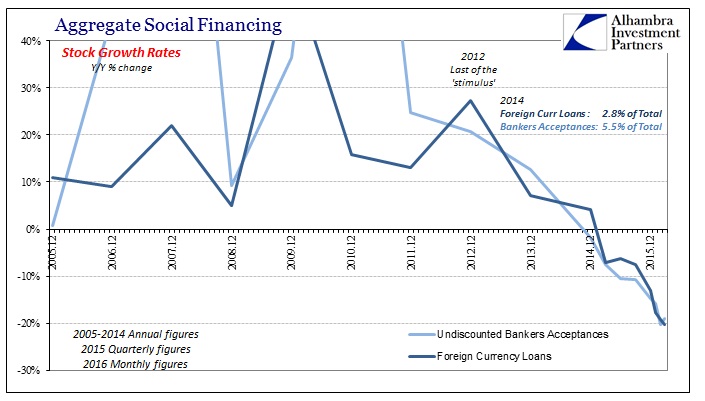

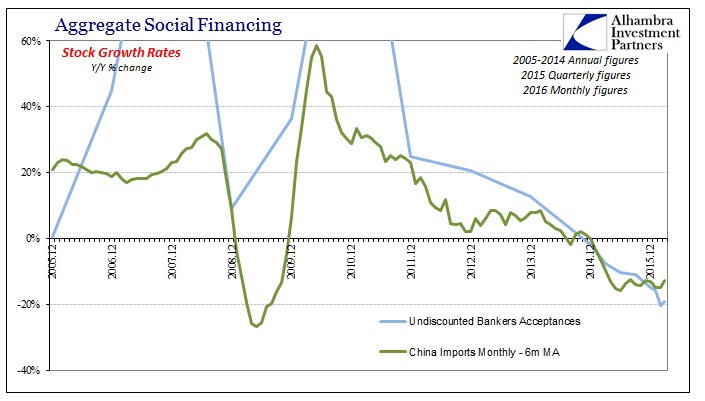

That being the case, it is not at all surprising to see Chinese real economy financing due to acceptances fall off dramatically around the “rising dollar” period. The Chinese system stock of acceptances grew by nearly 13% in 2013, which was much slower than the 20% annual increase from 2012. In 2014, however, acceptances actually shrank by 1.8% and likely most of that in the second half of the year. Since then, the contraction has only deepened, with Q4 2015 at -15% and so far in 2016 only worse, with February and March declining about 20% in each. The level of foreign currency loans has followed the same trend and together this behavior is very much like “capital outflow.”

The effect on Chinese financing “needs” overall has been stark. Prior to 2014, foreign categories and “inflows” were a heavy and even growing part of the TSF proportion.

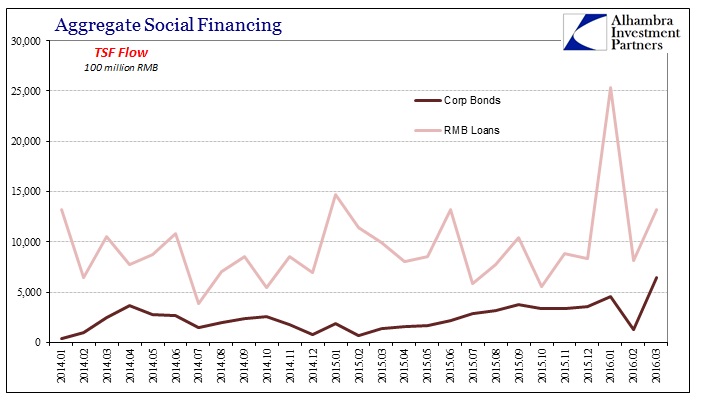

With the “dollar” portions slowing past 2012-13, the financial environment in China has been far more uneven. The decline in overall financing growth is rather large (and that includes not just these “dollar” parts but also internal RMB financing via trust products) so that internal lending is now the fastest growing portion of TSF. But internal lending remains somewhat slower than it was a few years ago, meaning the whole financial environment in China is an imbalanced reduction being driven first on “dollar” terms and then with relatively meager RMB responses.

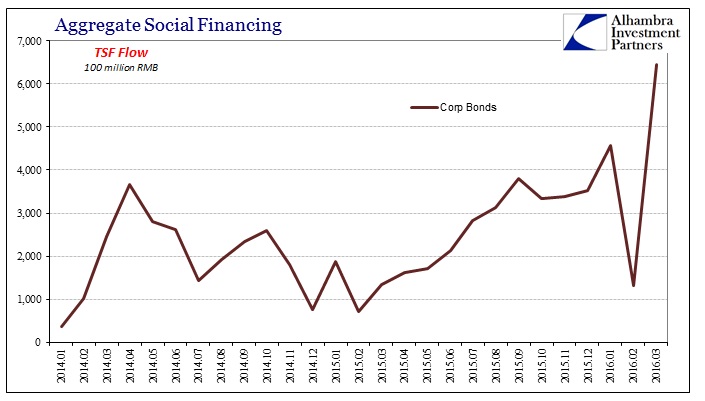

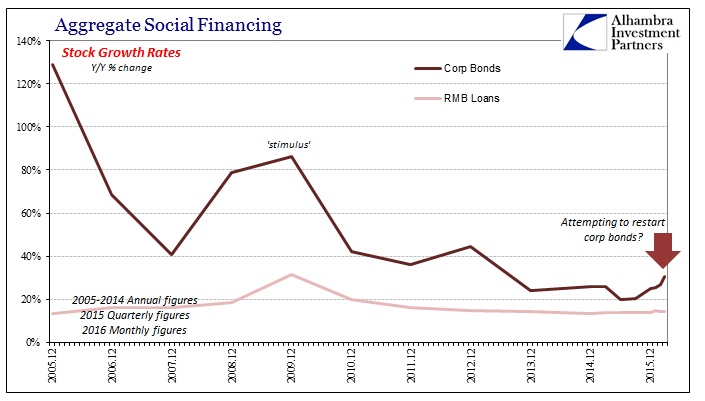

Part of that has been a steady increase in corporate bond issuance (in RMB), with more than RMB 600 billion net funded in March alone. While that looks impressive, it is far less so on the scale of the TSF or aggregate funding gap created by the external shortfall or even in comparison with past growth rates.

Where corporate bond growth rates (stock) accelerated to 30.6% in March, up from as low as 20% in Q2 and Q3 last year, that is still much less than 44% growth in 2012 or the “stimulus”-driven 86% growth in 2009. Meanwhile, the connection of bankers acceptances to the real economy is immediate:

There is causation on both sides here, as a decline in Chinese “demand” overall would lead to less “need” for bankers acceptances, but also that a “dollar” problem would certainly and heavily impact import activity. In other words, it is likely that imports would have started to contract in 2014 anyway on pure economic imbalances due to the industrial/export economy slowing, but the “dollar” problem in direct terms amplified the contraction into the disaster that we see; one that is being sustained no matter what the internal financing mechanics of the PBOC.

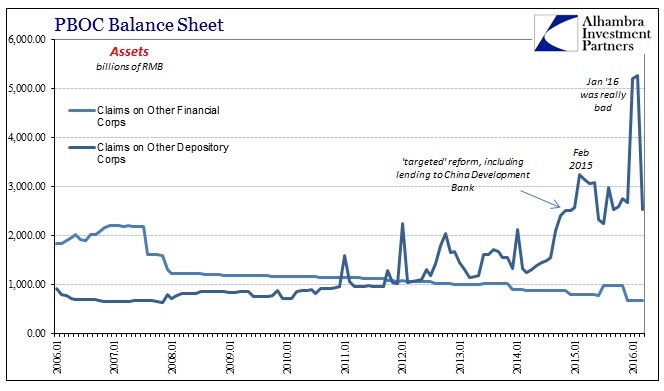

Part of the reason for that is that these are not perfect substitutes or even really close substitutes. The PBOC can only offer “dollars” in limited circumstances via forward injections as enticements for Chinese banks to further import them without any guarantee (subscription required) that they will be further used to finance China trade (PBOC forward cover is not at all the same as increasing the potential level of acceptances). On the internal side, an increase in China’s corporate bond issuance in RMB does not directly impact overall Chinese “demand” especially if China’s corporate sector is using corporate bonds in lieu of past lending commitment rollovers in anticipation of further illiquidity and disruption (which is exactly what US corporates did starting in 2009).

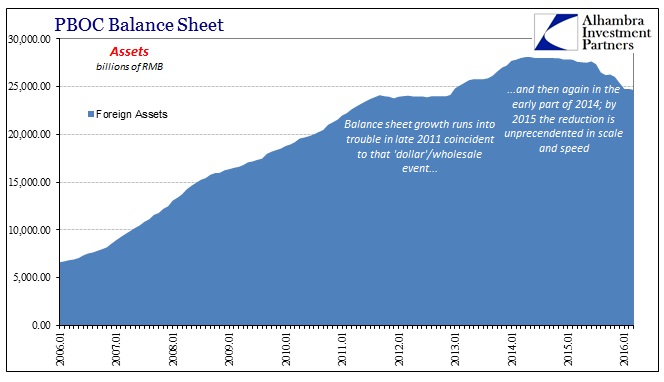

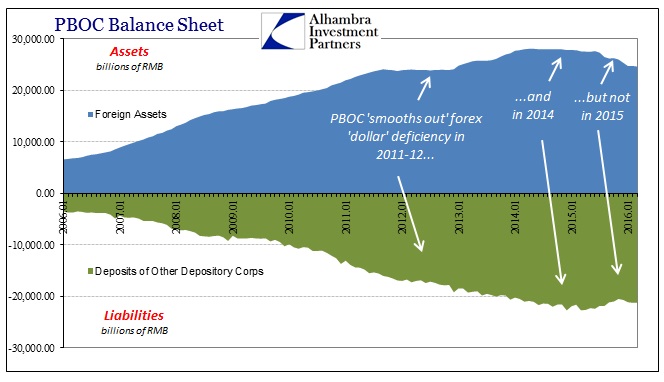

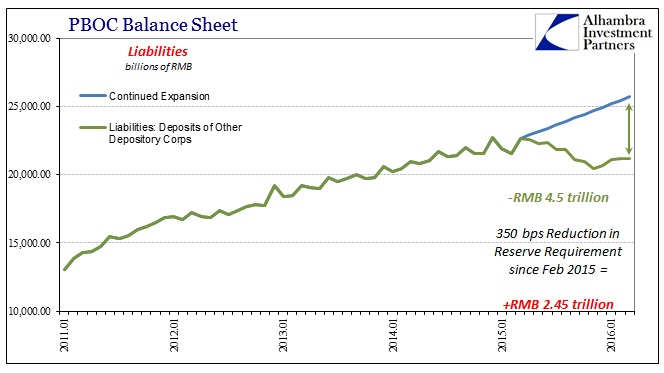

That means that overall while the numbers start to add up to internal RMB financing seemingly bridging the gap left from external declines, these are very different purposes. That is true even in the internal mechanics of RMB liquidity, where the drawdown in current (and future) “dollar” resources of the PBOC has forced further imbalance within the banking system’s monetary capacity. Though it has been better in the past few months, the base “money” level remains especially behind due to this external-driven “hole” in China’s financing “supply.”

A relatively small increase in bank lending or corporate bonds is not the same as replacing the exact funding sources that are now missing and consistently so. The best the PBOC or Chinese authorities can really hope for is to manage the “dollar”-driven imbalances by blunt interventions and encouragement, that some of this raw counterbalance will get somewhere effective as soon as possible. Unfortunately, everything is still subject to liquidity concerns, as you can see below in the unwinding of Lunar New Year programs.

It is very much similar to the mainstream hope that China’s service and consumer economy will make up for the ongoing and increasing industrial/export retreat. There, as here, it is wishful thinking because those are imperfect substitutes that require radical changes in order for the economy to transition, meaning that it will not be smooth assuming it is possible at all (I don’t believe it is, more so just an excuse to keep some optimism alive about China’s future). In aggregate financing, the PBOC can try to increase and incentivize the RMB sources of funding and finance but it isn’t the same as the reason financing is declining in the first place. Further, for that effort to be effective it would take years and growth rates commensurate if not beyond what used to be common (suggesting that if the PBOC is even attempting to do this on purpose they are several years too late).

It also suggests that China as the global economy pivot can’t even maintain proportionality between external demand for its own products and its own demand for foreign resources; the “dollar” is actually amplifying the depressive nature globally (which is really what you expect to find in situations of shrinking “money supply”).

In reality, what is occurring is likely far more basic. The “dollar” and export/industrial deficiencies are immediate and severe, so any RMB or internal efforts are merely attempts at maintaining minimal order in the Chinese economy and its internal markets until such time the “dollar” and the global economy finally settle out to some stable state. That’s the problem; it’s everyone’s problem and has been for almost two years running with no end yet in sight.