Last April, former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke wrote a series of blog posts for Brookings that was intended to explain one of the biggest contradictions of his legacy. If quantitative easing had actually worked as he to this day suggests that it did, why wasn’t the bond market in clear agreement? In order to try to reconcile the huge discrepancy, Bernanke offered several possibilities, even titling his effort “Why Are Interest Rates So Low?” to further emphasize the difficulty.

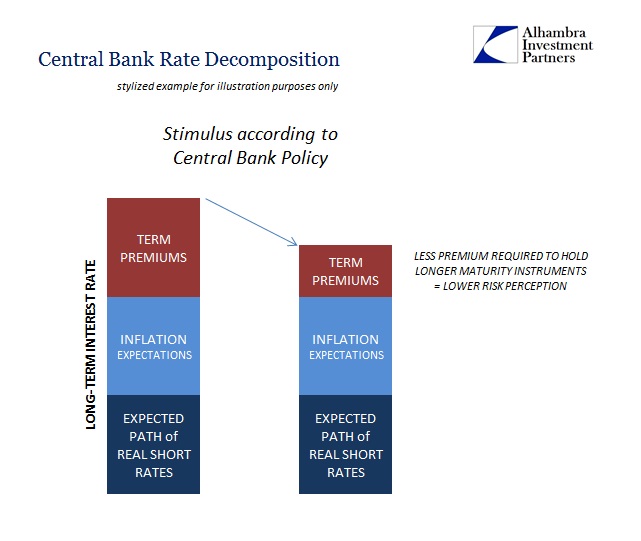

The fourth part of his series treated with “term premiums”, an element of Fisherian rate decomposition that economists use to try to understand bondholders and their motivations. In many ways, however, “term premiums” are a plugline, a leftover after considering the other perhaps more visible (this is a relative designation, as we always need to keep in mind that nothing presented here or that is discussed in policy or mainstream circles about these ideas is visible) parts of rate decomposition – expected path of real short-term interest rates and inflation compensation.

To Bernanke’s very obvious consternation, interest rates throughout 2014 only fell. Had QE been truly successful, interest rates would have continued as they did in the second half of 2013, the so-called “taper tantrum.” The media constructed that narrative to do as Bernanke was last year attempting – to reconcile how monetary policy that supposedly cannot fail would somehow find the bond market so unwilling to buy it. As Bernanke put it:

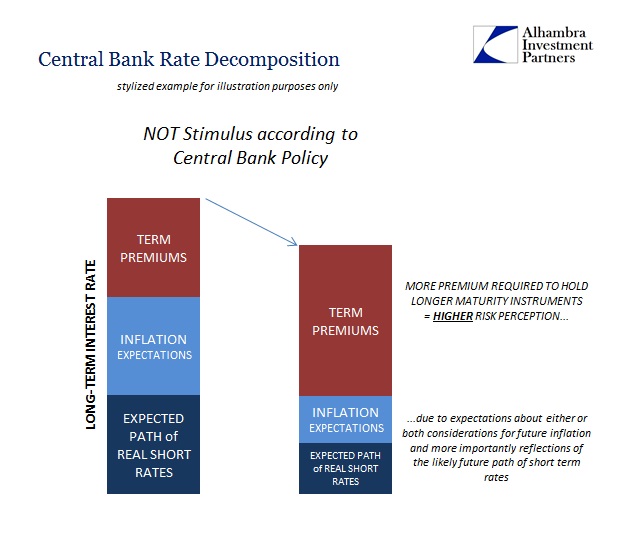

What about the decline in longer-term yields since early 2014? In the US at least, that decline is somewhat surprising, as economic fundamentals have recently seemed more consistent with rising, not falling, longer-term yields. The year 2014 was a good one on the whole for the U.S. economy, with three million jobs created, and longer-term inflation expectations appeared to remain stable. By the process of elimination, with fundamentals stable or improving, much of the decline in yields over the past year must reflect a sharp drop in term premiums.

He even provided a helpful graph which is given far, far more credibility than it deserves. On it he plotted the falling 10-year UST yield which is real enough, but then assigned a “risk neutral” yield as a way to distill the term premium he contended is embedded within the 10s. As nominal rates begin to fall in 2014, his calculated “neutral” yield actually starts to rise, leaving as simple arithmetic not just a sharply declining “term premium” but one that actually turns negative by early 2015. All he said with regard to this “neutral” rate is that it is “an estimate of what the 10-year Treasury yield would be if investors were indifferent to risk”, thus likely some statistical construction of orthodox assumptions and embedded properties.

Rather than settle the matter it only further aggravated the contradictions. How can “term premiums” be falling far more sharply under tapering and then ended QE than during it? Bernanke admitted that he didn’t know:

That naturally raises the question of why the term premium has recently fallen by so much. The answer is not obvious. Fed policy doesn’t seem to explain the decline, as purchases of Treasuries under the quantitative easing program wound down last year.

He suggested, weakly, that perhaps it was the US bond market viewing QE in Europe and Japan “spilling over” into UST expectations and thus “term premiums.” He also raised the possibility, however, that it could very well have been that which to orthodox economists cannot be: oil prices reflecting reduced inflation expectations as well as greater economic risks of a far weaker economy. To both those possibilities, however, he concludes, “the recent decline in longer-term yields and term premiums in the US remains something of a puzzle.”

The only reason it still is “something of a puzzle” is because he like the mainstream continues (to this day) to assume that QE works and even works well. From the point of view of effective “money printing” the behavior of the bond market has been and remains a complete mystery. Again, to reconcile these two very different positions (QE is effective stimulus but nominal interest rates don’t show it) requires the imposition of lower “term premiums” though the reason for them cannot be explained.

In a truly scientific endeavor, however, it would never end in such a manner; all assumptions would have to be re-evaluated from the start. In this case, that would mean rate decomposition and all its components.

As noted yesterday in what was really the first part of this discussion, lower term premiums are supposed to reflect lower perceived risks. That was one possible explanation for Alan Greenspan’s “conundrum” that Bernanke’s 2006 speech I referenced yesterday offered; that the Fed had been so successful in supposedly engineering the Great “Moderation” the bond market was reflecting even more faith in monetary policy genius from the early 2000’s forward. That would have manifested in this tortured delusion as lower term premiums just as the housing bubble mania was transforming to its initial stages of bust.

In this manner, lower nominal interest rates can be transformed (to an economist) from a naked contradiction to soft evidence, just as Bernanke was attempting to do all over again last year. From the benefit of hindsight we can see what should have been common sense even then (to be fair, Bernanke in his 2006 speech did not use this explanation as the likely case, he only raised the possibility in similarly groping for an answer that preserved his and the Fed’s dogmatic approach and interpretations) actually transpired. In other words, especially from 2006 forward it was the expected path of real short rates as well as to a lesser extent long run inflation expectations that were as much of a likely culprit for the “conundrum” as drastically reduced “term premiums.” In very general terms of decomposition, it could fairly be said that the bond market was worried about the potential outcome of the housing bubble as the same as all bubbles no matter how many times monetary officials congratulated themselves for a period of moderation that looked less and less moderate all the time.

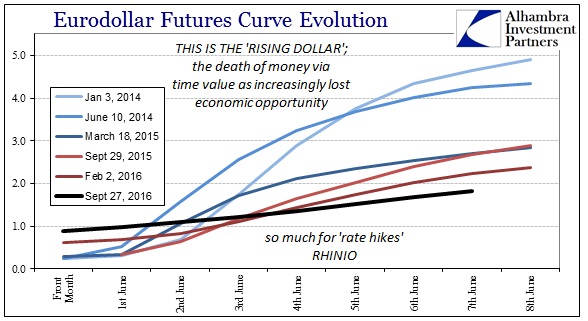

This latter view became far more realistic especially into 2007 where other means of potentially signaling the expected path of real short rates began to also refute. Primary among them was eurodollar futures, a topic I have discussed at length in other places. In other words, there is a great deal of actual market evidence that like the middle 2000’s the current “conundrum” in long-term rates is equally damning as unlike the happy scenario that Bernanke last year laid out that still ended with few actual answers.

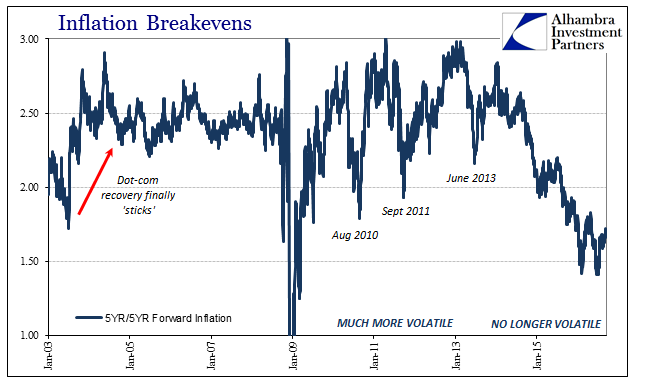

It really is that simple even if we can’t accurately measure any of these pieces individually. Unlike his “neutral” interest rate that leads to his favorable math of “term premiums”, we have very, very solid evidence that the current trajectory of low nominal rates if they could ever be so decomposed would be moving lower on the bottom two sections rather than the top (as shown above). Eurodollar futures, as noted yesterday, continue to reflect a truly unnerving future path of short rates, not one that leads in Yellen’s direction. At the very same time and in very corroborative fashion, TIPS trading has broken down inflation expectations into 2009-style lows.

Notice how both of these reductions are taking place exactly during the time in question starting in 2014 when “economic fundamentals have recently seemed more consistent with rising, not falling, longer-term yields”; the same years where Bernanke’s statistical reconstruction of some undeterminable “neutral” yield just so happens to produce a favorable term premium condition. And that gets us back to the central problem: economic fundamentals. Bernanke’s term premium view of lower nominal long-term rates would have expected by now a generous acceleration in economic activity befitting such seemingly auspicious market expectations. That was, after all, the whole point of his blog series; the economy was surely getting so much better so why wasn’t the bond market agreeing?

The decomposition of rates as I have shown them reflects the opposite interpretation and thus expectation. In other words, the bond market never agreed on economic fundamentals and has since been proven right for its contrary skepticism.

Again, it really isn’t that complicated but it is made so by orthodox econometrics that holds a very skewed view of the world and how all these things work. Economists would rather rely on very dubious reconstructions than admit to the simplicity. I should further clarify that my own view of interest rates is nothing like “term premiums”; rather I present these possibilities in economists’ own terms and language so as to further discredit them. Not even Ben Bernanke can save his legacy from the vindicated wrath of the bond market that still and increasingly reflects the curious lack of any economic opportunity. Once the world stops believing in the superstitions of term premiums and then stimulus that can’t even live up to their own conditions only then will recovery be possible.