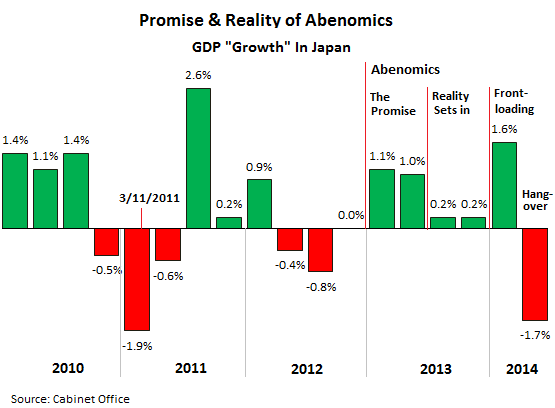

Japan’s economy has had, let’s say, its ups and downs. The big recent downs were triggered by the financial crisis in 2008 and by the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011. Both were met with stimulus packages and all manner of rebates and incentives that drove up the deficit and goosed the economy, only to leave a hole when they eventually wore off.

But since 2013, Japan has Abenomics – and its three arrows: promise, hype, and hope. It came with a huge bout of money-printing by the Bank of Japan, tax cuts for businesses, and a very broad-based consumption-tax hike to hit households the hardest.

It was passed by the prior government that was subsequently kicked out because of it. No one in Japan wants to pay for what the government actually spends. So the current rule is that only about half of government spending is collected in taxes, the other half is borrowed. Hence the insurmountable and rapidly growing pile of debt.

Abenomics had its moments. At first, given the soaring stock market and the feel-good atmosphere, the economy perked up, growing in the first half of calendar year 2013 at a nice clip. Then stocks tanked, optimism faded. Promise, hype, and hope were replaced by reality and by “inflation without compensation.” Hence near stagnation in the second half of 2013.

Then a miracle happened: The effective date of the consumption tax hike, April 1, the beginning of Japan’s fiscal year, moved closer and triggered a historic bout of frontloading by consumers and businesses alike. In an environment where money in low-risk investments earned nothing, and where inflation was rising, the government had handed consumers and businesses a way to save 3% at every major purchase. It’s like 3% risk-free income. For households, it was tax-free! Frontloading turned into a frenzy. And GDP jumped 1.6% in the January-March quarter.

It was the finest moment of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s regime, and Abenomics apologists scattered across the globe, praising his endless wisdom.

Then in the April-June quarter (Q1 in Japan), a terrific hangover set in. More than a hangover.

GDP plunged 1.7% from prior quarter, an annual rate of -6.8%, the Cabinet Office reported. It was the worst decline since January-March 2011 when the earthquake and tsunami on March 11, and the subsequent triple meltdowns at the Fukushima nuclear plant, nearly brought the Japanese economy to a halt, freezing up supply chains and transportation systems. Thousands of aftershocks, some of them serious earthquakes in their own right, continued to wreak havoc for months. Electricity was in short supply…. Those were terrible months. During that tragic quarter, GDP plummeted 1.9%.

That GDP in the April-June quarter this year was just two notches less terrible (-1.7%) is a sign that it wasn’t just a hangover from a bout of frontloading. It ate up not only the entire growth of the January-March quarter (+1.6%) but also half of the growth of the September-December quarter (+0.2%).

It’s not a pretty picture:

Note the sudden impact of the stimulus after the earthquake in 2011, followed by its big fade that lasted four quarters. That’s how stimulus works.

Then, in the first half of 2013, the beginning of the Abenomics era, the economy got high on promise, hype, and hope and on money-printing. In the second half, reality set in, and the economy languished. And so far in 2014, the net effect of frontloading and hangover is that GDP has actually declined.

The last quarter was ugly throughout. Consumption by households dropped 5.2%, and excluding “imputed rent,” 6.2%. Consumers drastically cut back on buying big-ticket items and confronted steep price increases while their incomes stagnated. Private residential investment plunged 10.3%. Only government consumption ticked up.

But that’s not the whole story to the GDP fiasco: Imports had soared during the quarter, compared to the same period a year earlier, while exports limped along. So the trade deficit for the quarter ballooned by 23.6% year over year. Trade deficits reduce GDP, and in the already terrible quarter, it was a hit below the belt.

The trade deficit had nothing to do with the consumption tax hike. Rather it is an ongoing, relentlessly deteriorating debacle. Rising exports and trade surpluses have always been vital to Japan. And reconstituting them is a cornerstone of Abenomics. But that plan has totally gone to heck. Read… The Flame-Out Of Abenomics, in One Crucial Chart