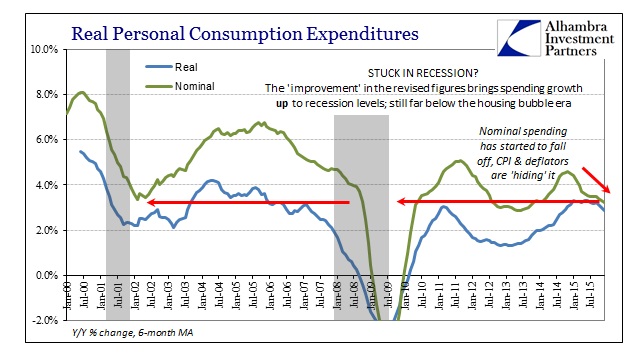

If China and US manufacturing are suffering from what looks like the contours of a slowly progressing recession, we don’t have to go very far to find the genesis. The common denominator is and has been US consumers. That much is evident in very clear fashion through retail sales during the Christmas season that were abysmal. The BEA’s update for full PCE figures shows mostly the same, even though overall PCE is highly influenced by “services” spending in the form of imputations and, where evident, services in the form of a tax (health care).

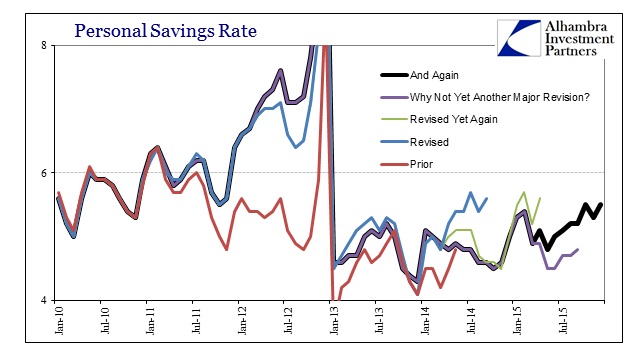

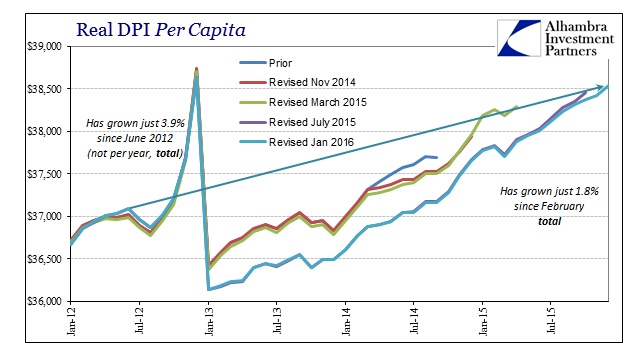

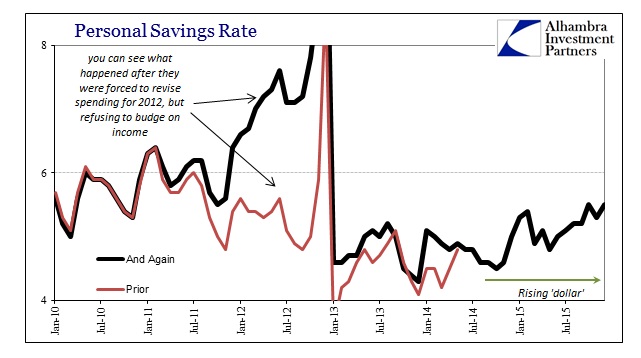

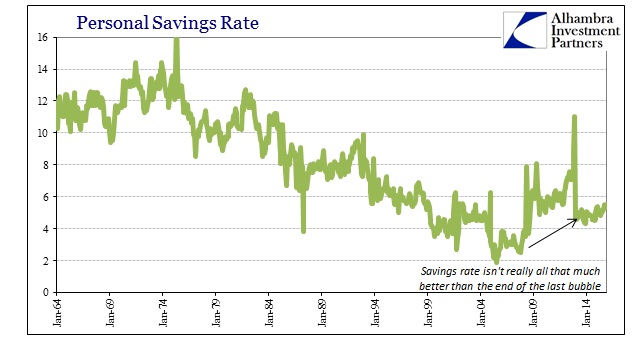

Real PCE spending was slightly negative in December month-over-month, which suggests another reason why GDP disappointed without too much snow or “residual seasonality.” That makes two of the last three months with essentially zero spending growth despite both what the BEA suggests as somewhat rising income and no “inflation.” This has been an issue with these data points for some time, as the BEA continually suggests that income is rising faster than spending only to revise income lower in persistent fashion. This dichotomy is highlighted by the personal savings rate, which in count of repeated revisions appears as just noise almost without discernable pattern.

Each time the savings rate moved up erratically (before the current spike) the BEA would eventually counter with a downward revision to income.

Even still, the current trend in income growth remains lackluster by any reasonable standard, which is worse than even that appears in “real” terms since there is little to no calculated “inflation” subtracted in the past year or so. As a result, the savings rate has risen to the highest since 2012 as consumers aren’t following these numbers.

In nominal terms, personal spending growth is as low as it was into the middle of the Great Recession and equivalent to the lowest point in the dot-com recession (just like 2012). The real PCE estimates would suggest that near-zero inflation is a significant difference in favor of the overall economic growth trend but the savings rate and other economic accounts show strongly otherwise.

That is all the more concerning given that the savings rate even on an upward trend here is relatively low to begin with; meaning that consumers have very little room to absorb any negative factors since they are spending (in historic terms) almost all their income just for minor positive numbers overall (for now).

For most of the Great Recession, the savings rate fluctuated between 4% and 6%; in September 2008, the rate was 4.4%, jumping to 5.4% in October 2008 and 6.2% the month after. The slope of the savings rate now is much shallower, but the direction remains (if or until there are income revisions again) to a somewhat similar degree. There isn’t much discretion and what little consumers have been able to find (despite “the best jobs market in decades”) they aren’t parting with; and no discernable “tax cut” from the gasoline/oil price collapse, either.

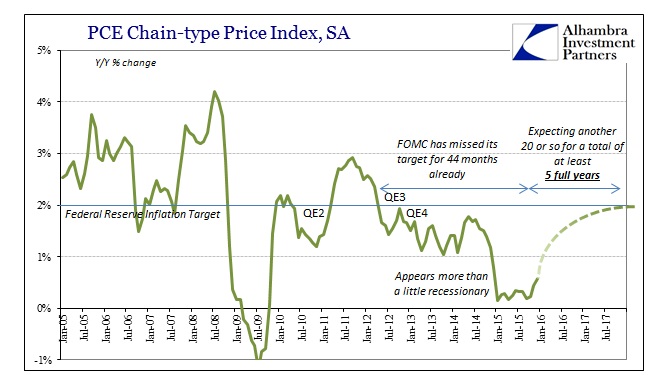

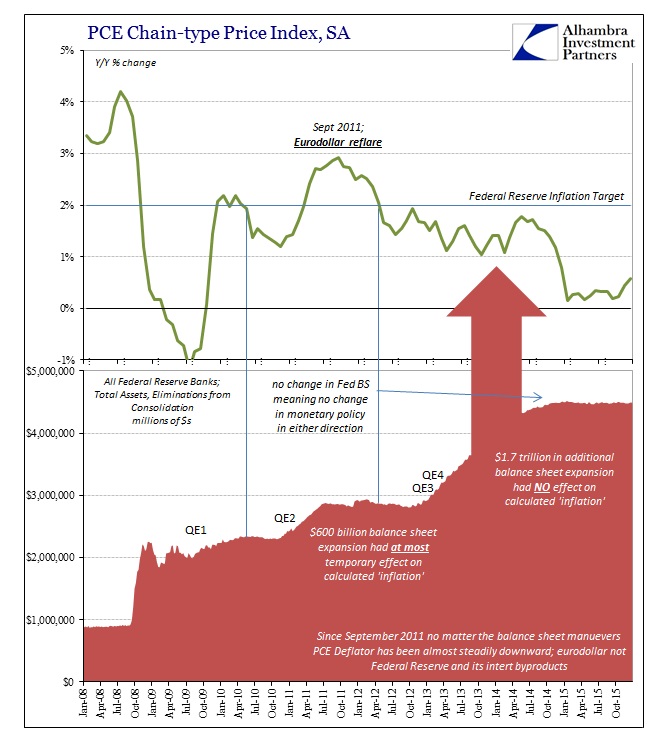

Instead, as far as monetary policy is concerned, December 2015 represented the 44th consecutive month of “inflation” undershooting the 2% price target for the PCE deflator. At 0.58%, it was the highest rate since December 2014 but it won’t last into January with at least the renewed commodity liquidation.

Instead, there is clearly no relationship whatsoever between the Fed’s balance sheet and the PCE deflator. That might suggest one more reason why the whispers of negative nominal interest rates have only grown since last year rather than perhaps the more expected appeal of a fifth QE. Whatever the ultimate case for monetary policy, there is nothing in the spending and income estimates that suggest the economy the FOMC claimed it expected toward “overheating.” Quite the opposite, as “underheating” appears to be widespread and more universal; maybe it’s not that QE was ineffective but monetary policy overall, just in time for increasingly serious economic concerns.