By Wolf Richter At Wolf Street

Bank lending has been setting new records since mid-2013. If the prior credit bubble – when too many loans were made helter-skelter by loosey-goosey loan officers before it all blew up in 2008 – was spectacular, this one is even more spectacular. It’s based on the principle that the US economy can only grow if bank lending balloons.

In November, bank lending began to tick up at a faster clip. Then suddenly with the New Year, as if someone had opened the floodgates in a drunken stupor, bank lending started to soar. Perhaps it was a consensus within the business community that interest rates would soon go up, that the Fed would not only taper QE out of existence but also raise interest rates sooner than its cacophony suggested, that this was the last chance to get free or nearly free dough, after inflation, and they all started borrowing like madmen.

The phenomenon has become reminiscent of the final ramp-up in lending seen in mid-2008, even as all heck was breaking loose in the financial sector.

This time, economists have been brandishing the borrowing binge as a sign that investment was suddenly picking up, that these investments would soon filter into economic growth, and that after five years of false promises and sour disappointments, the ever elusive “escape velocity” could finally be achieved.

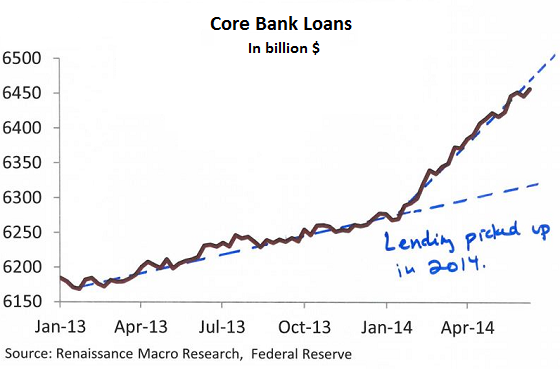

Back in April, I wrote about “The Bank Credit Bubble in America, Now Bigger Than the Last One (Which Blew Up).” Since then, the pace of lending has been relentless. And this is what the auspicious chart of core bank loans outstanding looks like (via OtterWood Capital Management):

Turns out, that jump in investment – powered by bank lending – that economists have brandished with such enthusiasm has been an illusion. And this time, it wasn’t some blogger spouting off party-pooper data, but the Financial Times, quoting sources of “senior executive” rank inside major US banks who “are privately warning” that the lending binge “should not be seen as evidence of an economic recovery.”

Instead, much of the borrowed money was used “to fund payouts to shareholders” via dividends and stock buybacks and to “finance acquisitions,” the source said. None of these activities have any productive effect. In fact, acquisitions lead companies to boast about synergies and efficiencies – that is, layoffs – at either end, as the businesses get consolidated.

And part of the borrowed money is being plowed into the US fracking boom where drillers have gotten on the terrible treadmill that fracking represents. The sharp decline rates of fracked wells force drillers to drill ever more just to maintain production, and they can never get off the treadmill because production would swoon, and with each well they have to borrow more, and then they require more production just to service the ballooning debt. Revenues have risen 5.6% over the last four years while debt that drillers have piled on has nearly doubled [read… The Fracking Shakeout].

“It’s crazy, it’s the boom, it’s the gold rush,” a senior corporate banking executive at a large US bank told the FT. “Small companies are becoming large companies overnight.”

“Loan growth doesn’t seem to be driven by the underpinning of an economic recovery in terms of new warehouses and [capital expenditure],” the executive said. “You don’t see the foundation, the real strong demand.”

Another corporate banking executive at a major regional lender told the FT: “The larger part of the usage in the market right now are loan refinancing where companies are paying dividends back out.” And that wasn’t all: “They’re requesting increased loans or usage under a lien in order to pay a dividend or equity holders of a company,” the source said. “Traditionally banks have been very cautious of that.”

The loans the source was fretting about – those that “banks have been very cautious of” – are leveraged loans that private equity firms use to strip out whatever value is left in their portfolio companies. These already overleveraged outfits borrow even more money from banks and, instead of investing it in productive activities that create revenues and cash flow with which to service the loan, they pay the money out the back door as a special dividend to the PE firms. It pushes the company deeper into the hole, enriches the PE firms, and saddles the bank with a highly dubious asset.

Bankers have thrown their now apparently silly concerns overboard, have loosened their underwriting standards, have watered down loan covenants, and whittled down risk premiums. While in the past, if they made those loans at all, they demanded being compensated for the nosebleed risks they were taking, and they’d charge an arm and a leg for these loans. As a result, companies stayed away from them. But these days, just about anything goes.

“Frothy” is how bank executives described the corporate lending market to the FT.

And how did the last lending boom of this type end? Bad deals are made in good times. Bad deals are made when the cost of money is nearly zero, when the Fed has inundated the corporate world and banks with cash, when risks have been printed out of existence. And these bad deals, the essential product of the largest credit bubble in history? They get pushed into dark recesses where they smolder quietly until they blow up. They did in 2008. And they’re going to again. It’s just a question of when.

Banks are again taking the same risks that triggered the financial crisis, and they’re understating these risks. It wasn’t an edgy blogger that issued this warning but the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. And it explicitly blamed the Fed’s monetary policy. Read…. Federal Regulator Details Crazy Risk-Taking By Banks And Blames The Fed