Energy investors have long hoped that falling prices would solve themselves by driving producers into bankruptcy and stanching the flood of excess supply, but it hasn’t worked out that way

By Timothy Puko and John W. Miller for The Wall Street Journal

October 24, 2016

Their owners may be bankrupt, but the sprawling mines of Wyoming’s Powder River Basin are still churning out coal. It is the same story in oil fields along the Gulf Coast and with shale-gas wells in the Rocky Mountains.

Energy investors have long hoped that falling prices would solve themselves by driving producers into bankruptcy and stanching the flood of excess supply. It turns out that while bankruptcy filings are up, they have barely impacted fossil-fuel markets.

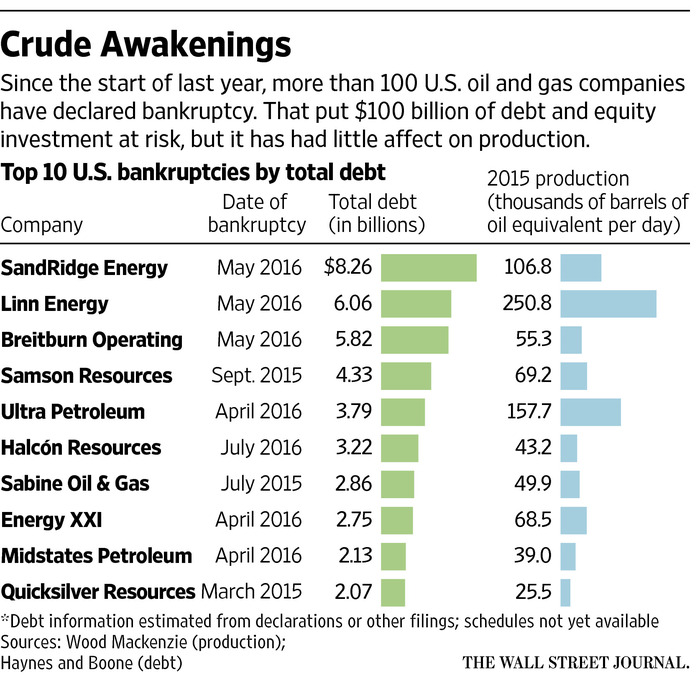

About 70 U.S. oil and gas companies filed for bankruptcy in 2015 and 2016. They now produce the equivalent of about 1 million barrels a day, about the same as before they declared bankruptcy, according to Wood Mackenzie. That represents about 5% of U.S. oil-and-gas output.

That resilience has kept energy inventories flush and prices capped. Oil shot to $50 a barrel this summer, but has had trouble making much progress beyond that mark. On Friday, oil futures in New York rose 0.4% to $50.85 a barrel.

The theory that bankruptcies would help balance the market “was misguided to begin with,” says Roy Martin, a research analyst at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie. “And people are starting to come around to that now.”

This is exactly the way chapter 11 was meant to work. The process is designed to save companies that can be saved, and many energy companies are using it to lighten their heavy debt loads, adapt to lean times and keep producing.

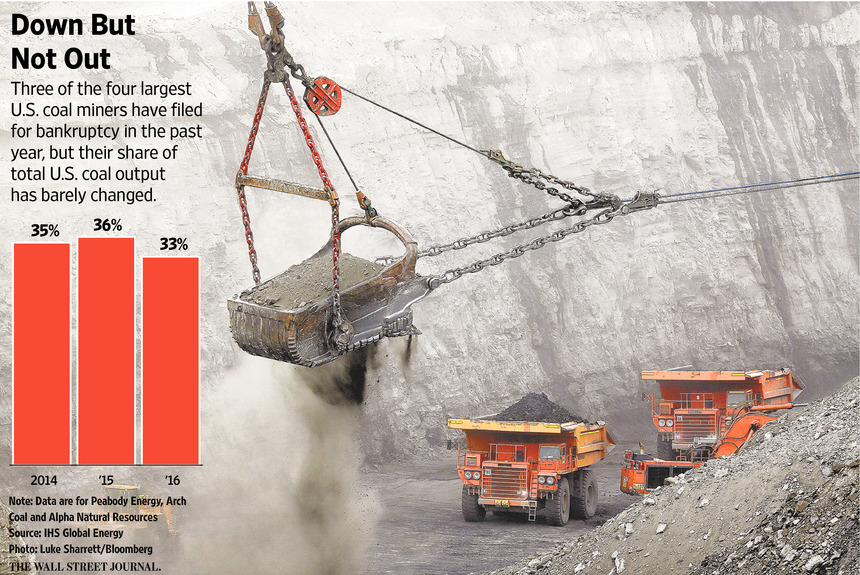

Peabody Energy Corp., Arch Coal Inc. and Alpha Natural Resources Inc.—three of the five largest U.S. coal miners—all filed for bankruptcy in the past 18 months. They accounted for about 36% of U.S. coal supply in the first half of 2015. This year, production declined only in line with the rest of the sector, and their share for the first six months was nearly unchanged at about 33%, according to IHS Global Energy. Arch Coal and Alpha Natural Resources recently emerged from bankruptcy.

“It is frustrating,” said Adam Wise, managing director at John Hancock Financial Services who helps oversee about $7 billion in energy-related debt and private-equity investments. “A lot of those companies just operate similarly to how they were prior to entering bankruptcy. It definitely doesn’t help.”

Oil hit historic lows this year and, while it has rebounded somewhat, at $50 a barrel it is just half of what it was three years ago. Oversupply continues to hamper the market and has forced analysts to retreat from earlier calls that oil would be at $60 or $70 by now.

Even accounting for recent drawdowns, oil producers and importers have added 18 million barrels to U.S. stockpiles this year, bringing the total to a near-record 469 million. There was enough coal on hand in the U.S. in July to fuel every coal-fired power plant in the country for more than 80 days, up from about 70 days’ worth in July 2015, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“Without a reset button, there’s no need for prices to go anywhere,” said Colin Hamilton,head of commodity research at Macquarie Group Ltd. “It is a long grind.”

Natural-gas prices have had a stronger rebound this year, but they, too, are still below the highs of 2013 and 2014. U.S. coal benchmarks have followed, with Central Appalachian coal up nearly 70% from a record low in the spring, but still down 15% from three years ago, according to S&P Global Platts.

The long-term decline in prices has led to the bankruptcies, but also to massive cost-cutting that helped producers keep mines and wells profitable.

Since 2012, Peabody Energy has laid off 1,650 employees and slashed annual capital spending to $111 million from $997 million. The upshot: three big mines in the Powder River Basin recorded a profit margin of $3.46 a ton in 2015, up from $3.45 a ton in 2011. Peabody’s operations in the region produce over 100 million tons a year, enough to power 16 million U.S. households, the miner says.

Midstates Petroleum Co. filed for bankruptcy April 30 and began drilling a new well the next day. The company stopped running some rigs ahead of bankruptcy, but kept one going after filing. Many companies kept honoring some contracts for rigs and well services, having planned drilling programs months in advance and still in need to produce revenue for paying off creditors.

Other companies that went through the bankruptcy process are now embarking on a quick return to stabilization or even growth.Halcón Resources Corp., SandRidge Energy,Inc., Goodrich Petroleum Corp. and Penn Virginia Corp. recently emerged from bankruptcy after spending two to six months restructuring. Combined, they shed about $7 billion in debt.

Goodrich plans to grow production “pretty dramatically,” President Robert Turnham told The Wall Street Journal. The recent rebound in gas prices makes drilling in Louisiana more profitable, and the company is employing new techniques to save money. They include reordering its well-site process to cut fracking time by more than half, Mr. Turnham said.

Ultra Petroleum Corp. has yet to emerge from bankruptcy—it filed in April—and it is already planning to add another rig within months and triple its fleet to 10 in about two years. The company has been renegotiating rig contracts and using bankruptcy laws to force pipeline companies to renegotiate other contracts.

“We get to run the company, and we’re trying to do what the bankruptcy rules or law suggests, which is to maximize the value of the company run as a growing concern,” Chief Executive Michael Watford said in an earnings call on Aug. 11.

Bank lenders, reluctant to actually take ownership of assets that have been used as collateral by borrowers, have been friendly to troubled companies. During bankruptcy, Halcón, SandRidge, Goodrich and Penn Virginia raised a combined $1.3 billion in debt, largely reaffirmed credit lines from their banks.

Coal magnate Robert Murray in 2014 correctly predicted that his rivals would file for bankruptcy. He pushed his Murray Energy Corp. to take advantage of the opening with a two-year buying spree fueled by $4 billion in debt. By this summer, Mr. Murray was negotiating with lenders, customers and workers on a multipoint plan he needed to avoid his own company’s bankruptcy.

His miscalculation: that his rivals’ bankruptcies would force them to cut back. If they maintain production, “that pulls everyone into what I call the bankruptcy sewer,” Mr. Murray said. “These are zombie coal companies chasing the ghosts of past markets.”

Original Article: Bankruptcy Bust: How Zombie Companies Are Killing the Oil Rally