The January retail sales report demonstrates perfectly the nature of this whole recovery, but especially the last year or so when everything holding to the primary narrative boils down to the unemployment rate – a statistic that is more and more determined by peculiar assumptions and calculations. The advance release from the Census Bureau had enough positive vigor to provide palpable enthusiasm in place of the very reluctantly increasing glumness.

Retail sales increased for a third straight month in January as Americans kicked off 2016 by spending freely on cars, clothing and online merchandise…

Greater job security, improving wage growth and falling gasoline prices may be persuading more consumers to loosen their purse strings after a fourth-quarter slowdown. A pickup in household purchases, which account for the lion’s share of the economy, would help the U.S. stave off the negative effects of a strengthening dollar, sluggish foreign demand and tumultuous financial markets.

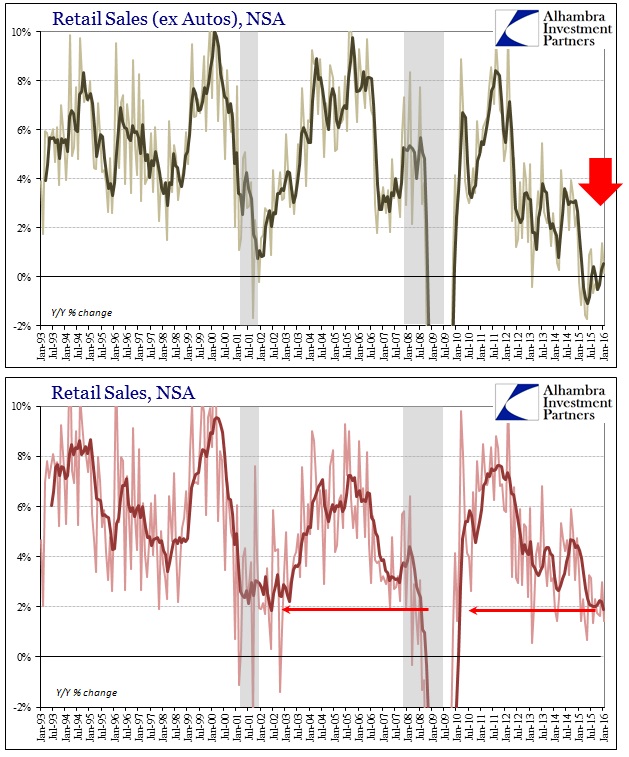

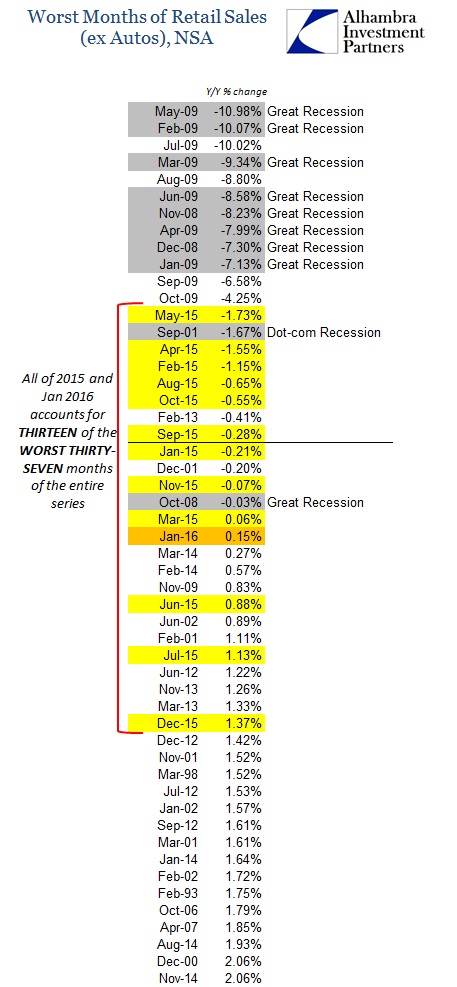

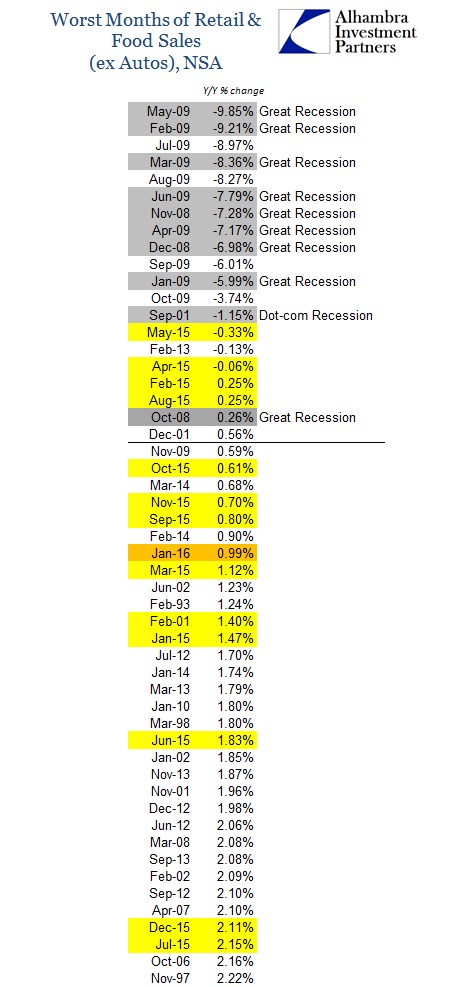

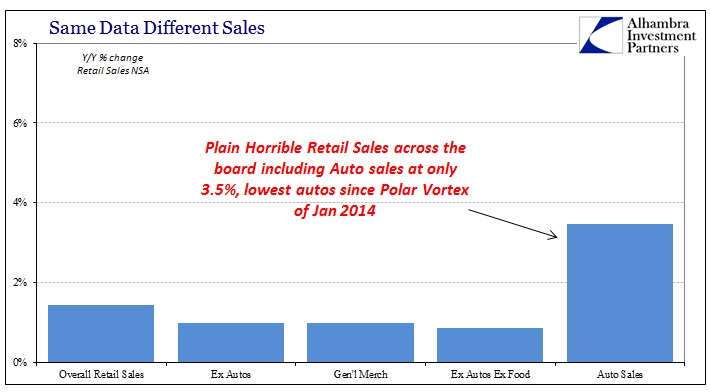

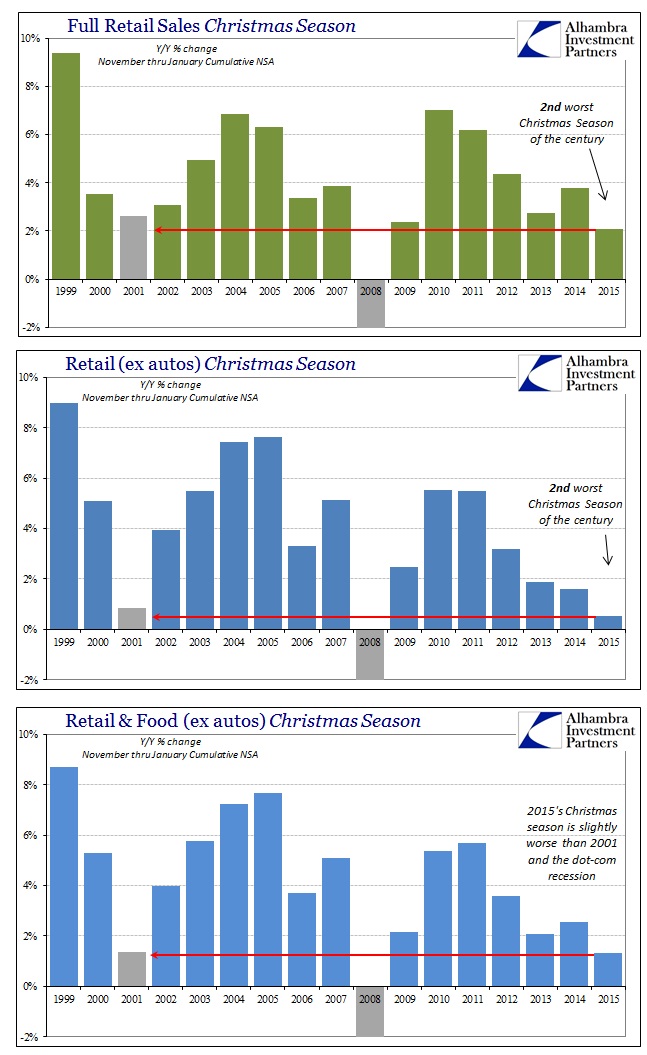

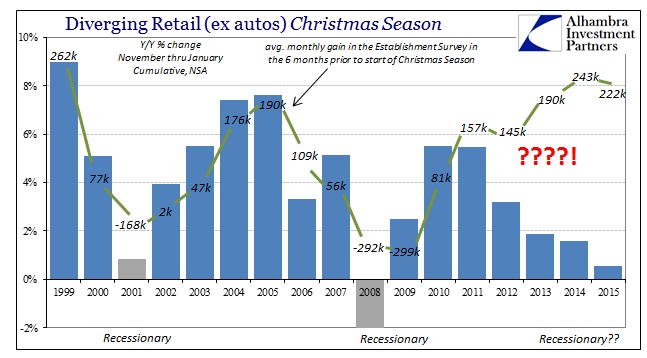

When initially searching for how or where consumers were “spending freely”, I failed to see anything resembling strength or “greater job security, improving wage growth”, etc. Instead, the retail sales report was the usual flavor of awful, with sales growth overall including autos just 1.44% in January. Strong consumers would be represented by at least 5% if not steadily above 6%. That rate was the same as the snowy cold of February 2015 and worse than the awful November that started the hugely concerning Christmas season. Auto sales themselves were up just 3.5%; a broad-based disappointment no different than the recessionary levels that have become alarmingly common since the end of 2014.

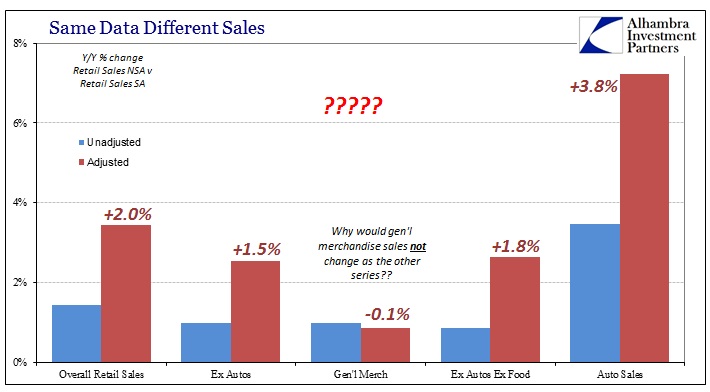

It wasn’t hard to find what the mainstream is relieved about, however, as there was a huge discrepancy with the “seasonally” adjusted figures. Seasonal adjustments are not just altered for seasonal swings month-to-month but they are also reconfigured by formula for differences in numbers of weekends or even the arrangements of holidays within the month, or even as compared to the same month in the prior year.

As you can see above, the results are not the same at all – especially auto sales. These kinds of adjustments make some sense in terms of very narrow analysis, but in the broader economic context it truly does not matter how many weekends fall within a particular month. Consumers get paid, largely, within a calendar month and they will spend that amount within that month no matter its configuration by days. Even if there were some residual effect in one weekend, how could that possibly account for the differences seen above?

Auto sales go from one of the worst months of the entire cycle, +3.5% unadjusted, to the same kind of robust growth that has marked this credit cycle, +7.2% adjusted. Further, if the calendar skew is so large in the other data series, why is it not for general merchandise stores?

Given the choice, economists and the media will choose the adjusted series every time no matter how far it removes from the underlying unadjusted estimates. Statistics in all its forms has become “more real” because math is believed to be objective science free from the entanglements of biases and assumptions. It is a false assumption to begin with, revealed quite easily in just these kinds of circumstances. The more managed and imputed the data since the middle of 2014, the more it has only led narratives and interpretations astray into confusion and misalignment; heavily disciplined figures are now the entire basis of the recovery idea. No wonder markets are inching past concern or worry into substantial and general fear.

Getting back to the less-assaulted numbers, the retail sales report was again the same brand of recessionary awful up and down including autos. With January, we can now fill out the complete picture for the Christmas holiday season, and it was astoundingly bad on every count.

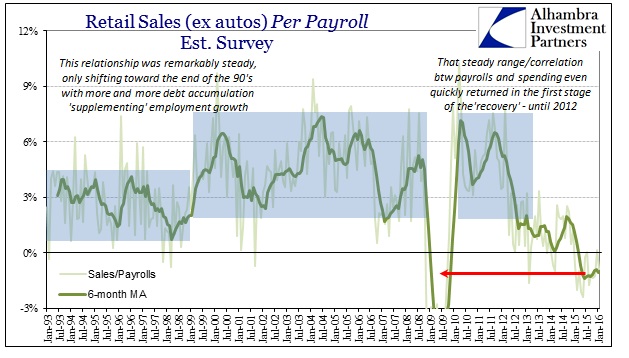

Further, and what I think is far more revealing along the same lines of manipulated number deviation, there is no relationship between the Establishment Survey’s highly adjusted data figures and the unadjusted count of retail sales spending (or even the seasonally adjusted estimates, for that matter). This is unprecedented as employment and spending had once been very closely related; it is only in the past few years where they no longer correlate (at all), during this “best jobs market in decades” that somehow doesn’t boost spending. Instead, retails sales, which are now suddenly the “lion’s share of the economy” under heavy seasonality, as described in the article quoted at the outset, have not just stagnated they are equal to, and in many ways worse than, past recession.

Phantom jobs, phantom income, phantom recovery; especially when the calendar gets involved. Is it more likely that consumers suddenly awoke and started “spending freely on cars, clothing and online merchandise” during January when the questions about recovery and recession, along with day-by-day market turmoil in every market, were the loudest and most visceral as they had been in years? And that isn’t even what the seasonally adjusted figures actually imply, however, as the correct interpretation is a counterfactual of consumers spending at a better pace in January had January been a “normal” January – in other words, dependent entirely upon the math defining “normal.” And that includes figuring out the “right” decline in spending from December, and then further determining whether just one month of these counterfactual adjustments are actually statistically significant (even the Census Bureau notes that they aren’t since the 90% confidence interval includes 0.0%).

Perhaps it is far more likely that spending was instead as continually awful as it has been for more than a year now. It sure seems that way without all the added math, which makes much more sense given the continued state of not just other economic accounts, those not so heavily adjusted, and foreign economies depending upon real spending rather than what that spending might have been under different calendar construction, but also now markets (primarily credit and funding, regardless of equities).