By Tyler Durden at ZeroHedge

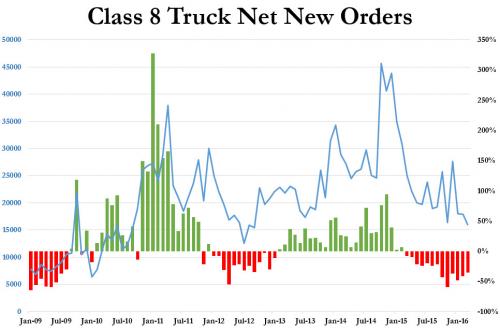

When we last looked at order of heavy, or Class 8, truck one quarter ago – that all-important, forward looking barometer of domestic trade – we said that even with 2015 in the history books, and as we start 2016 where the base effect was supposed to make the annual comps far more palatable, the latest, January data, as abysmal: “the drop continues to be one of Great Recession proportions, manifesting in yet another massive 48% collapse in truck orders in the first month of the year as demand appears to have gone in a state of deep hibernation.”

Fast forward one quarter when we now have another three months of Class 8 truck data, and unfortunately the orderbook has gone from bad to worse. As the WSJ reports, orders for new big rigs plunged and inventories of unsold trucks soared to their highest levels since just before the financial crisis, as uncertainty about future demand and a weak market for freight transportation weighed on truck manufacturers.

About 67,000 Class 8 trucks are sitting unsold on dealer lots, after sales in March dropped 37% from a year earlier to 16,000 vehicles, according to ACT Research. Class 8 trucks are the type most commonly used on long-haul routes. Inventories haven’t been this high since early 2007, said Kenny Vieth, president of ACT.

The number of March orders was the lowest since 2012.

The problem according to the WSJ? Simply not enough freight, or as some may call it, trade: “It boils down to, at present, there are too many trucks chasing too little freight,” Mr. Vieth said.

As the Journal adds, companies that placed large orders in late 2014, only for customers to move less freight than expected last year,are reluctant to buy more vehicles now, analysts said. Online freight marketplace DAT Solutions reported last month that spot market rates for dry vans, or the box trucks that are ubiquitous on U.S. highways, fell 18% between February 2015 and February 2016, an indication of weak demand.

“Fleets are being very cautious in the current uncertain economic environment,” wrote Don Ake, a vice president with FTR Transportation Intelligence, which reported similar order numbers for March. “Freight has slowed due to the manufacturing recession, so they have sufficient trucks to meet current demand.”

Some examples:

Aaron Tennant, owner of Simplex Leasing Inc., a trucking company in Jamestown, N.D., said that last June, anticipating market growth, he placed an order of 115 new Navistar International Corp. trucks to replace 75 trucks and expand his fleet to 245 vehicles. But that growth has not come. “Once this order is complete, I’m probably not going to consider buying any new trucks until at least October or November,” he said. “It’s definitely coming from caution. The market has softened in the last year.”

Meanwhile, the backlog is growing: Stifel analyst Michael Baudendistel wrote in a note Tuesday that the backlog of Class-8 trucks appears to be about six months, and said that truck and truck component manufacturers like PACCAR Inc., Navistar and Meritor Inc. are likely to see further pressure on their share prices and earnings.

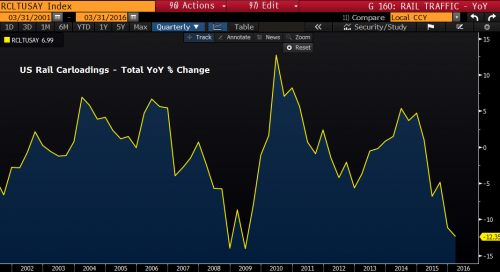

But it’s not just trucking weakness. As BMO’s Brad Wishak notes, for the first 12 weeks of 2016, U.S. railroads reported cumulative volume of 2,905,113 carloads, down 13.7% from the same point last year, while Canadian railroads reported cumulative rail traffic volume of 1,540,562 carloads, containers and trailers, down 5.3 percent yoy, largely due to a drop in coal shipments but indicative of a decline across all product lines.

An obvious conclusion is that despite all the talk of a rebound in economic growth and domestic and global trade, the facts on the ground simply do not confirm this.

So, as we asked four months ago, should one be concerned by this precipitous drop? Absolutely not: as the Federal Reserve would certainly say “it’s probably nothing.”