By Caitlin Huston at MarketWatch

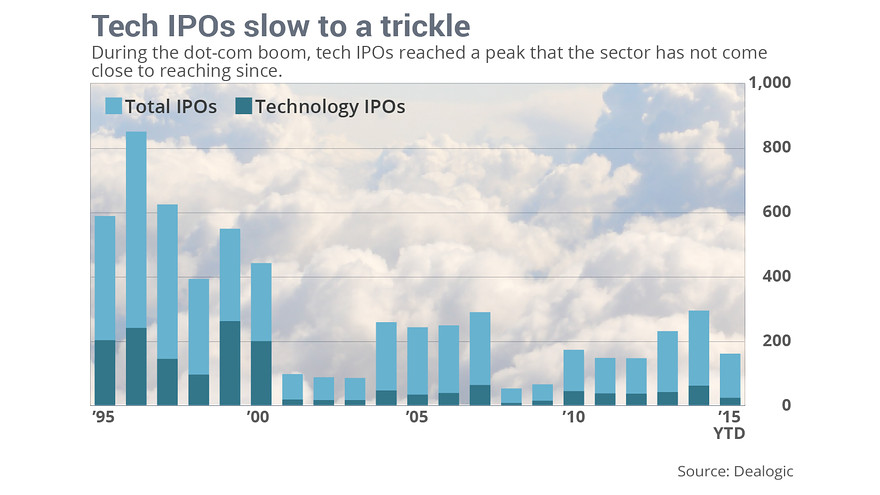

In the late 1990s, some technology companies with little more than a website to their names rushed to go public. Many were greeted by receptive investors before their stocks crashed when the bubble burst.

Today, technology companies have largely avoided initial public offerings because of the availability of private funding. Many that have gone public have performed poorly, offering little incentive for others to do so — and, some investors say, signaling a cooling in late-stage valuations as investors scale back. Meanwhile, hot biotechnology stocks are raising questions about another bubble in the public markets.

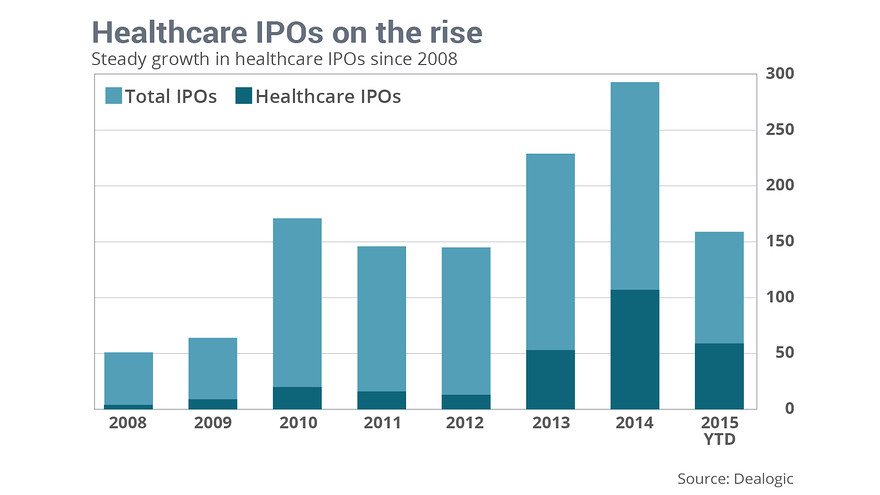

IPO numbers illustrate both trends. In 1999, there were 547 initial public offerings priced, with 260 from the technology sector. The next year, there were 440, with 198 coming from the technology sector. But of the 293 IPOs that priced in 2014, 107 were from health care. So far this year, 59 of 159 were health care companies, most of them in the pharmaceutical category, which encompasses biotechnology.

Meanwhile, technology companies have been slow to turn to the public markets for funding. There are now 125 private tech startups with valuations of $1 billion or more, 70 receiving the “unicorn” designation since the beginning of 2014, according to Dow Jones VentureSource. Only 14% of 2015’s IPOs in 2015 have come from the technology sector, which would represent the lowest percentage since before the last boom if it holds through year’s end.

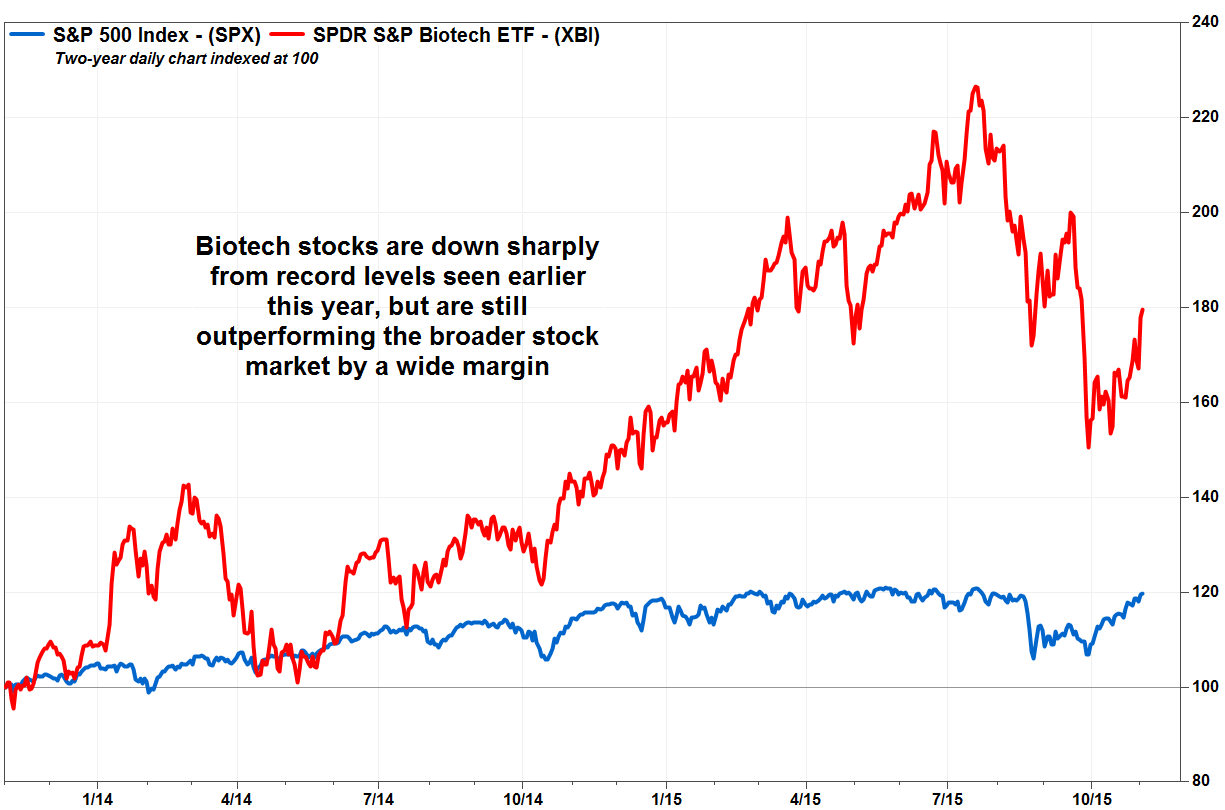

Investors attracted to the mission of biotechnology companies, which marry technical innovation with the goal of curing diseases, have also been drawn by the sector’s momentum. The XBI XBI, -0.58% which tracks biotech companies in the S&P Total Market Index, has gained 80% in the past two years, well ahead of the S&P 500’s SPX, -0.41% 20%.

The sector has also seen a frenzy of mergers and acquisitions this year, with 357 U.S. deals as of Oct. 21, for a value of $262.65 billion; last year there were 325 deals worth a total of $203.45 billion. The deal values are the highest in 20 years, illustrating the intensity of the search for the next generation of pharmaceutical products.

“Investors have been taken up by the fact that there are new ways to treat disease, especially cancer,” said Kathleen Smith, principal at Renaissance Capital, a manager of IPO-focused ETFs. But the sector’s IPO volume has also led to concerns that the market is overheated, according to Smith, who called it “the biggest sector change and biggest worry that investors might have.”

Many biotech IPOs are for relatively small amounts of money, notes Richard Peterson, senior director of Standard & Poor’s Investment Advisory Services, suggesting that fears of a bubble may be overstated. The largest deal in pharmaceuticals since 2014 was Catalent Inc. CTLT, +0.90% a drug development company, at $1 billion, according to Dealogic. The next largest was Axovant Science Ltd. AXON, +1.95% at $362 million.

But some worry that the companies going public lack revenue, earnings or proven ideas. “A lot of them I see [go public], and I just scratch my head,” said Andrew Farquharson, managing director of InCube Ventures, a life sciences venture firm.

Others have attracted scrutiny even before their IPOs. Theranos, an acclaimed startup valued at $9 billion, was recently highlighted by The Wall Street Journal for reportedly failing to use its promised technology in its blood tests and has since been at the center of a media firestorm over its business practices.

Some say the biotechnology bubble is already deflating. On Wednesday, the XBI closed 20% below its record close of $90.36 on July 17. The S&P 500 is 1.3% below its record close of 2,130.82, set May 21.

Others are less concerned. Paul Nolte, senior vice president of Kingsview Asset Management, believes investors have shifted from the health-care sector to now-safer bets on consumer staples and utilities. “All you’re seeing here, I think, is a rotation,” he said.

While biotechnology has boomed in the public market, other technology startups have amassed outsize valuations in the private market.

Only 16 U.S. venture-backed companies gained valuations of $1 billion or more from 1999 to 2000, according to Dow Jones VentureSource. The Wall Street Journal Billion Dollar Club, which tracks the total number of startups valued at $1 billion or more, had 125 members, ranging from ride-hailing behemoth Uber Technologies Inc. to Kabbage, an online loan company valued at $1 billion, as of Nov. 1.

Behind those valuations are large amounts of venture capital, often meaning going public isn’t a pressing need. There was more venture capital invested in U.S. startups in the first three quarters of 2015, $57.9 billion, than in all of 2014, when $56.5 billion was invested, according to data firm CB Insights.

Regulation may have contributed to the slowdown in tech IPOs. Going public became more expensive after 2002, when the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which required companies to comply with provisions including a mandatory report on internal controls over financial reporting, was passed.

Investors still complain about the costs associated with IPOs, though the 2012 Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act mitigated them somewhat. “They don’t see the advantage to it because of the cost involved in filing and just the day-to-day operation of being a public company,” said Peterson.

Much of the recent venture capital funding has been led by rounds of $100 million or more, meaning it is going to a relatively small number of companies. The third quarter of 2015 had 37 such mega-rounds, largely represented in late-stage deals.

That is partly a reflection of an investing herd mentality that can be traced back to Facebook Inc.’s FB, -1.54% 2012 IPO, said Sam Hamadeh, chief executive of PrivCo, a financial data provider that specializes in private companies. Investors saw a fast-growth company, bolstered by a large user base, not necessarily revenue, in an otherwise flat economy.

Since then, the hope has been that there will be another Facebook-like company. Players outside venture capital, such as mutual and hedge funds, have jumped in, which has driven up valuations, said Jeremy Levine, a partner at Bessemer Venture Partners. “All you need is one person who’s willing to pay a higher price,” Levine said.

But not every company can be Facebook, notes, Hamadeh, leading to “questionable companies” in the billion-dollar club.

The stock market saw a correction in August as Dow Industrials fell more than 1,000 points and the S&P 500 fell to its lowest level since October 2014. That brought down public valuations of former unicorns like Fitbit Inc. FIT, +1.68% Box Inc.BOX, +0.62% and Etsy, Inc. ETSY, -9.88%

Analysts say Wall Street investors have been mostly logical in their responses to company earnings hits and misses. After huge gains early in their Wall Street lives, big names like Twitter Inc. TWTR, -1.71% and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.BABA, -3.58% have come back down, even falling below their initial prices. “The public markets seem to be sane when valuing these [types of] companies,” Levine said.

Wall Street seems to be growing more discerning, making downward moves faster. First Data Corp. FDC, +4.57% which was the largest U.S. IPO of 2015, went public Oct. 15 and had a bumpy debut.

But the private market hasn’t responded in the same way, according to Levine. Investors are saying valuations and funding rounds are unreasonably high, he said, but they haven’t stopped investing.

“The dam has not broken,” Levine said. “I have not seen the behavior stop.”

Paul Boyd, managing partner at ClearPath Partners, however, says investors are paying more attention to company financials. That means it may be more difficult for the lower-tier members of the billion-dollar club to continue raising money and valuations will go down. Companies that don’t effectively manage their capital would become targets for the large tech players on the public market, said Boyd, who expects extensive M&A activity over the next 24 to 36 months.

But, if there is an end in sight, Boyd said he believes it will be a healthy change for the private market.

“It’s not nuclear winter,” said Boyd. “It’s just the normal season of winter.”

Source: Here’s Where You’ll Find the Next Tech Bubble – MarketWatch