It’s anecdotal evidence, but it’s everywhere in San Francisco and Silicon Valley. A neighbor was cooling her heels by the curb, suitcase next to her. She’s going to Europe on a “vacation-thing,” organized and paid for by her company, she told me. A team-building perk. She’s a coder at a startup, her first job out of college. When she moved in less than two years ago, trucks kept pulling up to deliver her latest acquisitions. One day, she gingerly parked a new BMW in the garage. As we were chatting about her trip to Europe, a limo pulled up for her ride to the airport. That too was part of the perk. No expenses will be spared.

This startup occupies super-expensive San Francisco office space that’s way too big for the number of employees. It’s embellished with designer furniture. Free lunches are de rigueur. All paid for with the boundless money it is getting from investors.

But who cares, except for a few wayward souls in the VC community who lament those sizzling burn rates. Bill Gurley, partner at Benchmark, had stepped to the forefront a few weeks ago to warn that “the average burn rate at the average venture-backed company” is at an “all-time high since ‘99 and maybe in many industries higher than in ‘99” [“Excessive Amounts of Risk” Doom Startup Bubble].

Marc Andreessen, founder of long-forgotten Netscape, then warned in a series of tweets: “When the market turns, and it will turn, we will find out who has been swimming without trunks on. Many high burn rate companies will VAPORIZE.” His final and most eloquent tweet: “Worry.”

Some other VCs chimed in when they had a minute, in between throwing even more cash at these companies to drive their valuations ever deeper into the stratosphere: in the first half, they’d thrown $15.6 billion at them in later-stage financing rounds, the Wall Street Journal reported, on track to break the record of $28.4 billion set in 2000, the year of peak craziness as the whole scheme was already collapsing.

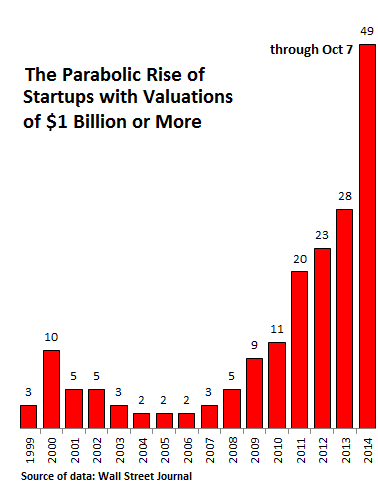

So now, 49 US startups that have not yet gone public and have not yet been acquired have valuations of over $1 billion, with five of them in, or nearly in, the $10 billion club. Uber tops the list with a valuation of $18 billion. And Snapchat, one of these $10-billion outfits, doesn’t even have revenues yet though it might eventually by selling ads via its disappearing messages.

Never before have there been that many startups with $1 billion valuations. The prior record was set last year when 28 companies achieved that milestone. In 2000, before it all collapsed, 10 startups had valuations over one billion. A parabolic rise of mega-valuation startups:

The overall IPO market has been whipped into a frenzy this year, with the most startups going public in the first half since 2000. But not the $1-billion-and-over kind; only 7 of them have gone public, including Alibaba that decided to sell its shares to US investors rather than to investors in China where it belongs. By contrast, in 2000, 38 companies with valuations of $1 billion or more were pushed out the IPO window.

They have their reasons for not going public. Some of them, like Snapchat, don’t have revenues, so convincing even exuberant investors to pay top dollars would be a slog. While that may not be a problem for zero-revenue Biotech startups that proffer the hope for a blockbuster drug, it’s a big problem for social media companies.

Other startups have revenues but are spilling prodigious amounts of red ink. That hasn’t kept them from going public, as the Twitter IPO has shown. Hope is a powerful motivator. There have to be other reasons why so many of them remain in private hands.

Turns out, it’s easier for VCs to multiply their paper profits if these startups do not go public. It’s easier because they control the valuations to a large extent. They don’t have to rely on the finicky stock market that has a nasty tendency to close the IPO window and crush these stocks just as the party is really hopping.

Pre-IPO “valuations” are an artifice decided behind closed doors within a tight community where everyone benefits if the valuations are ratcheted up relentlessly. In the current climate of boundless liquidity and near-zero returns on conservative investments, there is plenty of liquidity sloshing around, waiting for the next opportunity to book a paper profit. That paper profit is nearly guaranteed as long as everyone believes that everyone believes that valuations will be higher in the near future.

Look at Snapchat. It was driven from an already dizzying valuation of $2 billion last November to $10 billion earlier this year, with investors putting in an amazingly tiny amount of actual money. That kind of return would be hard to accomplish even in a frothing-at-the-mouth IPO market [read…. How to Rig the Entire IPO Market with just $20 Million].

This game of multiplying valuations and paper profits in the shortest time is so appealing that the startup scene is drowning in liquidity from all over the world. But how will they get their money out? Who will bail VCs out of these sky-high valuations and give them real money?

Two options: A corporate buyout, such as Facebook’s decision to print $19 billion of its own shares to buy a tiny messaging app maker. These miracles of corporate finance are always cool. Or an IPO. But in these mega-valuation startups, potential gains will have been harvested by private investors. And when time comes to go public, retail investors are likely to end up holding a deflating bag.

This is the rosy scenario. It assumes that the stock market, perched on top of its own ludicrous valuation, doesn’t get spooked beforehand. But there are signs that it is already getting spooked. Then all bets are off. Corporations get stingy, the IPO window closes, and what does get pushed out, experiences a hard landing, or simply shatters on impact. And suddenly the new money dries up. Startups with high burn rates can’t replace their cash and simply flame out. That’s the scenario Andreessen had warned about. It will be the sort of financial bloodletting people will remember for years.

The Dow was down over 300 points today. IPOs may experience hard landings. It’s suddenly tough out there. Even gold, it has been through heck. But wait – unlike the still prevailing exuberance for stocks, gold sentiment is at a historic low. Read….. The Calm Before the Storm in the Gold Market