By Mehreen Khan at The Telegraph

“Shunto” season has failed to grip Japan.

The country’s annual Spring assault on wages seems to have passed with little more than a whimper this year despite being billed as one of the most anticipated economic events in Japan’s recent history.

Translating as “spring wage offensive”, Shunto marks the annual Japanese ritual of wage bargaining between business groups and labour unions.

This year’s negotiations have been preceded by months of feverish lobbying from prime minister Shinzo Abe who has urged the country’s business groups to raise wages and help smash Japan’s deflationary mindset once and for all.

The wages issue has become the latest lightning rod in the country’s two decade struggle to ensure long-term economic prosperity.

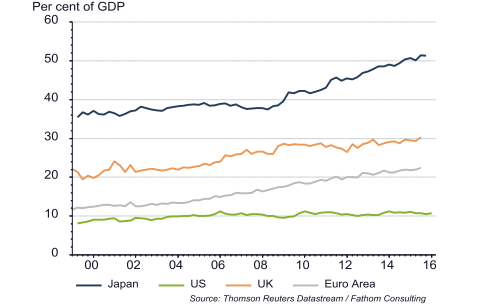

Higher salaries encourage consumption and are vital in raising inflation. This in turn would help erode some part of Japan’s record 250pc of GDP debt pile – the highest of any developed country in the world.

Tokyo’s calls have been echoed by some of the world’s most renowned economists.

Olivier Blanchard, the former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund and Adam Posen, a former Bank of England policymaker, have pushed for an unprecedented 10pc increase in nominal wages in 2016. In the last two years, average wages have risen by just 1pc.

“What is needed is a jump-start to a wage-price spiral of the sort feared from the 1970s”, say Posen and Blanchard, who call for a “virtuous cycle” of wage growth, inflation, and lower debt to release Japan from economic stagnancy.

Japan Inc.: cash rich, wage poor

But like so many of Tokyo’s radical attempts to extricate itself out of low growth and low inflation, the early signs show that Shunto has already fallen flat.

Car-making giant Toyota is reported to have agreed on a wage settlement which will boost its employees’ basic wages by just ¥1500 ($13) a month, despite recording bumper profits of ¥2.17 trillion ($19bn) last year.

Overall, the fruits of 2016’s Shunto are set to be more meagre than those of last year. Unions are demanding wage hikes of 3.27pc this year, lower than the 3.74pc of 2015, according to analysts at UBS.

This indicates the average eventual increase will be just 0.3pc for the country’s 63.5m workers, down from 0.69pc agreed in 2015, calculate economists at JP Morgan.

This reticence to raise wages puzzles economists.

Nearly four years on from the start of the government’s Abenomics programme, Japanese companies are sitting on record cash piles equivalent to nearly 50pc of the country’s entire economic output.

Export-oriented sectors have benefited from a cheaper currency while record low interest rates and monetary stimulus has helped ease financial conditions for over three years.

Other labour market indicators are also showing encouraging signs.

Unemployment has fallen to just 3.2pc, its lowest level since 1997. The ratio of available jobs to applicants also points to further declines in joblessness to come. More and more women and elderly Japanese have also re-entered the workforce to plug labour shortages.

And yet wage inflation remains the elusive “missing ingredient” in Japan’s nascent revival.

“If the Abe administration were able to achieve this, it would help enormously in combating the economic malaise that has dogged the country for much of the past two decades”, note economists at Fathom.

‘A busted flush?’

In recent months, Abenomics feted “arrow” of central bank stimulus has been accused of overshooting to such an extent that it is now actively hindering wage growth and denting business confidence.

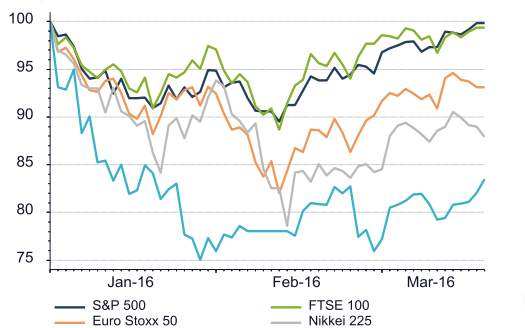

Specifically, the Bank of Japan’s landmark decision to enter negative interest rate territory at the end of January has ushered in a wave of panic rather than comfort over the power of central banks to stimulate moribund economies.

Negative interest rates have sparked global concerns over the profitability of commercial banks and led to stock price falls across the developed world.

Japan’s foray into sub-zero rates – intended to help weaken the currency – has also seen the yen unexpectedly strengthen by 7pc against the dollar.

This appreciation places a further constraint on wage largesse.

“Firms are surely incorporating the recent strengthening of the yen into their profit forecasts for this year,” says Marcel Thieliant at Capital Economics.

Having decided to carry out the most radical experiment in monetary stimulus in modern history , buying up 80 trillion yen in government debt every year, there is now increasing disquiet within the ranks of the central bank over its next move.

The initial decision to plunge into negative territory caused a five-four voting split among the BoJ’s nine members in January.

Following the market paroxysms, two members of the Policy Board voted to change the interest rate structure to provide greater protection for commercial lenders.

Haruhiko Kuroda, central bank governor, has admitted that the computer systems of some banks have suffered technical problems as a result of processing negative-rate transactions.

Abenomics is now risk of becoming a “busted flush” warn Fathom, as the economy is trapped in a unique bind.

For the last two decades, Japan’s ever rising national debt has helped support growth in nominal GDP, or the total cash size of the economy.

But with the pace of economic growth falling behind rising debt, and inflationary pressures failing to materialise from either higher wages or a weaker currency, Japan’s policy mix seems to have hit the buffers.

In their three-pronged assault on stagnation – comprising of monetary stimulus, government spending, and structural reforms – policymakers have succeeded only in generating “cognitive dissonance”, says Duncan Wooldridge, economist at UBS.

“It’s not just about achieving a 2pc inflation target. The deeper issue has always been that government debt has been consistently growing faster than the economy for years,” says Wooldridge.

With the economy having contracted sharply at the end of last year and inflation currently flat at 0pc, the Bank of Japan is widely expected to unleash another round of interest rate cuts and more QE next month.

Meanwhile, the embattled Abe government will be hoping the eventual outcome of this year’s Shunto – unveiled in June – could yet provide some welcome light relief.

“The struggle continues”, says Wooldridge.

Source: Can Anything Rescue Japan From the Abyss? – The Telegraph