Fracking has caused an uproar in local communities and split some in two. It has brought environmentalists to a boil. It allegedly caused tap water to go up in flames. A documentary was made in its honor. It caused earthquakes in Oklahoma and other places. It caused Wall Street to froth at the mouth. And now it is causing the balance sheets of oil and gas companies to blow up.

It always starts with a toxic mix. Now even the Energy Department’s EIA has checked into it and after crunching some numbers found:

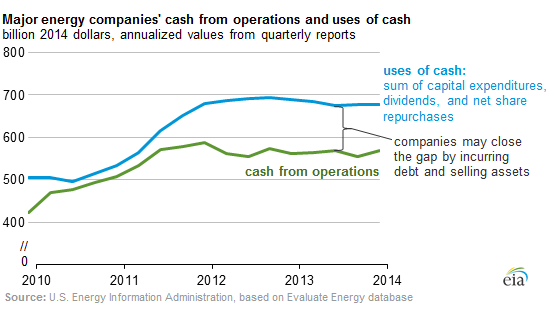

Based on data compiled from quarterly reports, for the year ending March 31, 2014, cash from operations for 127 major oil and natural gas companies totaled $568 billion, and major uses of cash totaled $677 billion, a difference of almost $110 billion.

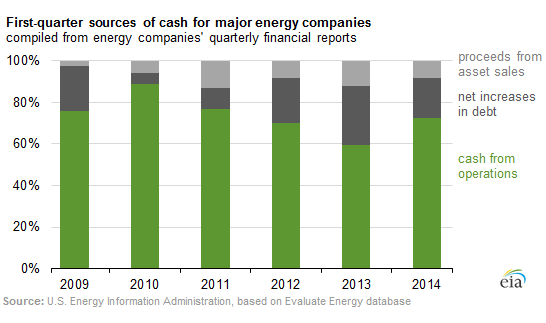

To fill this $110 billion hole that they’d dug in just one year, these 127 oil and gas companies went out and increased their net debt by $106 billion. But that wasn’t enough. To raise more cash, they also sold $73 billion in assets. It left them with more cash (borrowed cash, that is) on the balance sheet than before, which pleased analysts, and it left them with a pile of additional debt and fewer assets to generate revenues with in order to service this debt.

It has been going on for years. In 2010, the hole left behind by fracking was only $18 billion. During each of the last three years, the gap was over $100 billion. This is the chart of an industry with apparently permanent, horrendously negative free cash-flows:

And those shortages in each year forced the companies to raise more debt and sell assets to fund more drilling, other capital expenditures, operational costs, dividends, and stock buybacks.

Of the three sources of cash – operations, net increase in debt, and asset sales – during the first quarters going back six years, net increases in debt accounted for over 20% of the incoming cash since 2012:

The EIA was quick to minimize the issue, claiming that this debt that has been spiraling out of control wasn’t “necessarily a negative indicator.” That low interest rates allowed companies to get fresh debt capital to cover their operational cash shortages. And that piling on debt “to fuel growth is a typical strategy, particularly among smaller producers.” And besides, this ballooning debt would be “met with increased production, generating more revenue to service future debt payments.”

This is where debt smacks into fracking. Fracked wells have horrendous decline rates. They differ from well to well, with some estimates pegging the average declines at 50% to 78% by the end of the first year. After a few years, production might be down to less than 10% of production in the first year. In other words, the cash that has been drilled into ground has to be earned back within a terribly short time and has to be used to pay off the debt incurred in drilling the well. If not, the debt is left over, when the well is producing just a trickle.

This is exactly what is happening. It’s a horrendous treadmill. Just to maintain production, companies have to drill more and more and incur more and more debt, even as revenues are disappointing. In addition, drillers with heavy reliance on natural gas have faced prices for dry gas that have been so low for years that most wells will never generate enough cash to cover the costs of production. And the capital that went into them has been destroyed.

A Bloomberg analysis of 61 companies drilling for shale oil and gas found that debt among them nearly doubled over the past four years, while revenues inched up only 5.6%. And interest payments on that ballooning debt is taking up an ever larger portion of the revenues – even at today’s record low interest rates – with 12 of the companies already paying over 10% of their revenues in interest.

The financial hype around fracking, the limitless, nearly free liquidity provided by the Fed since late 2008, and investors so desperate for yield that they’re willing to incur just about any risks in their vain battle to come out ahead have had Wall Street frothing at the mouth. The sweeps of creative destruction have broken down. Instead, the boundless stream of money has been searching for a place to go, and it went to an economic activity – fracking – where money goes to die. What’s left is debt, and wells, especially gas wells, that will never produce enough to pay off the debt that was incurred to drill them.

These binges can go on for a long time, for far longer than a sane person in normal times would think possible. But with revenues barely growing, cash flows from operations stagnant, and debt levels that are soaring, at some point, something has to give.