It was the introduction of two Latin words that doomed the modern discipline of economics. As the mathematical modeling craze swept into what is now econometrics, the derivation of theories and, more importantly, the statistical “evidence” of those theories rested upon ceteris paribus – “with other things the same.” It is difficult to accept even the basic proposition that one could hold all other variables equal while testing only one or two given the extreme complexity, the most of which is actually taking place in the relation of factors to each other. You can’t isolate effects when everything affects everything else.

In the minutes of the May 27, 2013, Bank of Japan policy meeting, participants recognized the basic orthodox premise of currency-based economics:

They shared the view that exports had recently bottomed out and were likely to pick up, supported by a moderate recovery in overseas economies and the yen’s depreciation in the foreign exchange market.

It’s a simple enough proposition that seems to hold intuitive sense; weakening the exchange value of a particular currency and, ceteris paribus, exports should pick up as they become relatively cheaper on foreign markets against competition. The inverse holds true for imports, as they become relatively more expensive (though even orthodox economists admit that there has to be some relatively close domestic substitutes to make this side work).

This was expressed, at that monetary policy meeting, as increasing confidence in long-term prospects in Japan based mostly on this presumed currency dynamic.

They shared the recognition that, from fiscal 2014 toward fiscal 2015, while affected by fluctuations in demand stemming from the scheduled consumption hikes, the economy was likely to continue growing at a pace above its potential, as a trend, as positive developments in domestic private demand were likely to continue, supported by increasing exports and monetary easing effects.

At the outset of BoJ QE10 this trend was taken and incorporated solely on faith not just in Japan, but across the globe. Back in April 2013, it was common for Japan’s trading partners to leak and make noise about concerns over “currency war.” Such was the proposition that a huge devaluation would be so very effective as to be detrimental to trading partners.

The Bank of Japan’s decision is likely to spark concerns that Tokyo is deliberately depressing the value of its currency in a bid to improve its export performance in a tough global trading environment. The yen fell sharply after the decision was announced, losing about 3% of its value against the dollar in Asian trading.

David Bloom, currency strategist at HSBC, said: “Policymakers will likely hope that yen weakness will be a side-effect of their QE strategy, but given the sensitivity of ‘currency war’ accusations, they will not want to actively target the exchange rate through rhetoric.”

By the latter part of 2013, the idea of “currency war” had taken official positions and was beginning to foment back-channel criticism. The Council on Foreign Relations in October made a point to highlight this potential diplomatic contention, while unquestionably accepting all its precepts.

The effects of Abe’s policies will have a long-standing impact in the international arena, especially as the world’s export-led economies like Germany and China begin sounding off warnings about a currency war, otherwise known as competitive devaluation, where countries vie for low exchange rates to boost demand for domestic industry.

There has been no doubt about the behavior of the yen, as it experienced massive devaluation against the majors. But the net “boost” has been less than uniform or even obvious. In fact, the actual trade data lies in direct contradiction to the orthodox currency “rule.”

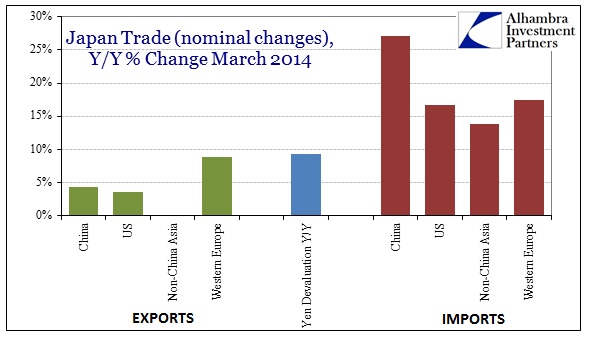

Among Japan’s largest trading partners, those that have seen the most devaluation, the results shown above should be switched if the currency devaluation assumptions were valid. Exports to China were up only 4.3% in March 2014 Y/Y, but imports from China surged 27.1%; these results have been typical and are not limited to the latest monthly results. In the last 12 months the yen has depreciated about 9%, but exports to the US only grew by 3.6% in nominal terms. That is why the Census Bureau figures imports from Japan in dollars show persistent declines.

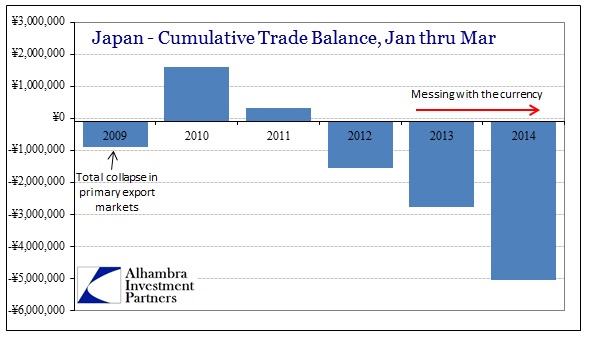

Nowhere is the orthodox currency position at all evident – there has been no export boost. Worse, flying in the face of all these assertions the evidence is absolutely clear that Japan has actually fallen further behind by nearly an order of magnitude.

In the first three months of 2009, during the worst collapse in post-war global economic history, the trade deficit in Japan was less than ¥1 trillion. Even allowing for the change in energy needs post-tsunami, there is no way to explain the first three months of 2014 and preserve the idea that Japan will both revive on its trade balance and use it to maintain forward, healthy growth. The deficit so far this year has quintupled the 2009 figure.

The reason can be traced to ceteris paribus. There are immense and powerful counterforces that cannot be simply ignored as they are with academic, mathematical modeling. The two most evident are the offshoring of Japan Inc. and the lack of revival in those export destinations (another factor, asserted above in the BoJ minutes, that was simply taken on unshakable faith). This is most stark in Japanese trade with the rest of Asia, once a geography where the Japanese were unquestionably dominant.

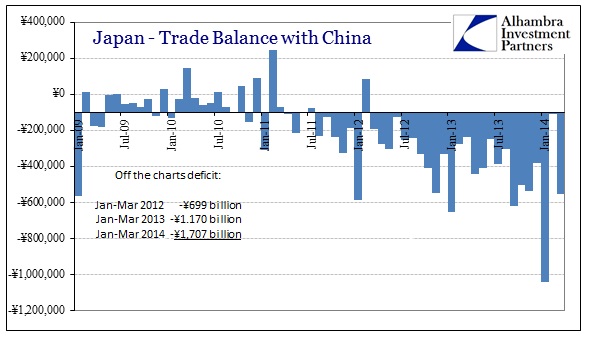

It is clear from the trade data with China that so much production capacity has moved from Japan just recently (and since China is not a major energy exporter, particularly to Japan, energy cannot account for this massive shift).

The trade deficit with China is now nearly two and a half times as large in 2014 as it was before the Bank of Japan began banking on currency intrusions. And March’s data strengthens that point as it existed beyond any seasonal or holiday fluctuations that may have influenced January’s disastrous results.

These orthodox assumptions about how economies may be intentionally managed are flawed in their most basic forms. The talk of “currency war” is now passé, showing that trade partners no longer fear the devaluation as they did less than a year ago. That is perhaps the plainest rebuke to these orthodox pieties from inside the policy class as there has ever been, but it never goes further than that to redefine the discipline and its assumed efficacy.

It really is that simple, that if you cannot understand the complexities of a system there is absolutely no way to initiate and maintain control. The Japanese trade system is the most obvious reflection of that, particularly since Japan has grown exponentially poorer as a result of what was supposed to be unquestionably beneficial. That lesson applies across the entire spectrum of orthodox means of economic control and in every jurisdiction where it is practiced.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@alhambrapartners.com