Nicole Foss: Our consistent theme here at the Automatic Earth since its inception has been that we are facing a very powerful deflationary depression, following on from the bursting of an epic financial bubble. What we have witnessed in our three decades of expansion and inflation is nothing short of a monetary supernova, and that period has been the just culmination of a much larger upward trend going back many decades at least. We have lived through a credit hyper-expansion for the record books, with an unprecedented generation of excess claims to underlying real wealth. In doing so we have created the largest financial departure from reality in human history.

Bubbles are not new – humanity has experienced them periodically going all the way back to antiquity – but the novel aspect of this one, apart from its scale, is its occurrence at a point when we have reached or are reaching so many limits on a global scale. The retrenchment we are about to experience as this bubble bursts is also set to be unprecedented, given that the scale of a bust is predictably proportionate to the scale of the excesses during the boom that precedes it. We have built an incredibly complex economic system, but despite its robust appearance it is over-extended, brittle and fragile after decades of fuelling its continued expansion by feeding on its own substance.

The Automatic Earth, December 2011: The lessons of the past are sadly never learned. Each time the optimism is highly contagious. In the larger episodes, it crescendos into euphoria, leading societies into a period of collective madness where risk is embraced and caution is thrown to the wind. Sky-high valuations are readily rationalized – it’s different here, it’s different this time.

We come to believe that just this once there might be a free lunch, that we can have something for nothing. We throw ourselves into ponzi finance, chasing the mirage of speculative gains, often through highly questionable and outright fraudulent practices. Enron, Lehman Brothers, and recently MF Global, are but a few egregious examples of what has become an endemic phenomenon.

The increasing focus on chasing speculative profits parasitizes the real economy to a greater and greater extent over time. After all, why work hard for small profits in the real world, when profits on money chasing its own tail are so much greater for so little effort?

Who even notices the hollowing out of the real economy, or the conversion of large amounts of capital into waste, or the often pointless depletion of non-renewable resources, or the growing structural dependency trap, when there is so much short term material prosperity to pursue?

In such times, the expansionary impulse drives the development of multiple engines of credit expansion. The reserve requirements for fractional reserve banking (already a ponzi scheme) are whittled away to almost nothing. Since the reserve requirement effectively determines the money supply multiplier effect, that multiplier becomes almost infinite.

The extension of credit through the shadow banking system removes the semblance of central bank control over monetary expansion. Securitization and financial innovation also create putative wealth from thin air, using underlying collateral to derive layers of additional illusory value. In this way, excess claims to underlying real wealth are created. The connection between the rapidly expanding virtual worth of the derivative instruments and the real value of the underlying collateral becomes ever more tenuous.

Shadow Banking and Phantom Wealth

Since 2011, in our desperate attempt to avoid the consequences of an imploding bubble, we doubled down on the doomed strategy of ponzi credit expansion. In doing so, we have only succeeded in digging ourselves into a deeper hole, and have done so on a massive scale. While the aggregate balance sheet of the world’s central banks grew exponentially from $3 trillion to $22 trillion over the last 15 years, the expansion in the shadow banking sector has been even more dramatic, and its role in fostering the overall credit hyper-expansion has become increasingly clear:

Shadow banks are that exploding growth segment of global finance capital that share the following characteristics: they are largely unregulated, they invest primarily in financial asset securities of various kinds (i.e. stocks, government and corporate junk bonds, foreign exchange, derivatives, etc.) instead of real asset investment (plant, equipment, software, etc.), they target high risk-high return opportunities based on asset price appreciation and volatility to realize financial capital gains, their investments are highly leveraged and debt driven, their investment targets are highly liquid financial markets worldwide that enable a quick entry, price appreciation, and subsequent just as quick short term profit extraction.

Their client base is predominantly composed of the global finance capital elite – i.e. the roughly 200,000 worldwide ultra and very high net worth individuals with net annual additional income from investment flows of $20 million or more—for whom they invest individually as well as for themselves as shadow bank institutions.

Shadow bank ‘forms’ include private equity firms, hedge funds, asset and wealth management companies, mutual funds, money market funds, investment banks, insurance companies, boutique banks, trust companies, real estate investment trusts – to note just a short list – as well as dozens of other forms and newly emerging initiatives like peer to peer lending networks, online investment funds, and the like.

Shadow banks have been estimated to have investable assets (i.e. relatively short term and liquid) of about $75 trillion globally as of year end 2014, a total that does not include revenue from ‘portfolio’ shadow-shadow banking. That is projected to exceed $100 trillion well before 2020.

The exponential growth of both central banks and shadow banking during the long global boom constitutes a gargantuan increase in the supply of money plus credit relative to available goods and services, which is inflation by definition. This huge supply of virtual wealth has acted to push up asset prices, creating a plethora of asset price bubbles and a cascade of malinvestment based on those price distortions. The explosive growth of shadow banking in particular, following the 2009 bottom, was accompanied by a return to extreme risk complacency and rock bottom interest rates, leading to a frantic search for investment returns in riskier and riskier places.

Inherently risky emerging markets became a major focus during this time, and the search for outsized returns not only sought out risk, but actively increased it. Volatility provides the momentum that generates trading profits, but it also creates considerable instability. Given that finance is virtual, and that changes in the financial world therefore unfold far more quickly than the real economy can realistically adapt to, large influxes and exoduses of hot money looking for quick profits are very destablizing to target sectors of the real economy, and to entire countries. The phantom wealth generated by the shadow banking bonanza has both created and subsequently fed upon real world destruction:

What China, Argentina, Greece, Venezuela, and Ukraine all share in common is an ongoing struggle with global shadow bankers, who continue to destabilize their financial systems and drive their real economies, at different rates, toward recession and worse….

….Shadow banks and their finance capital elite clients make money when financial asset prices are volatile, i.e. when such prices rapidly rise or fall or both. It is thus in their direct interest to cause asset price volatility and instability—whether in provoking a rapid rise in government bonds rates (Greece), in contributing to the collapse in currencies (Venezuela, Argentina), or in IMF-enforced ‘firesales’ of companies (Ukraine). Their strategy is to exacerbate, or even create, financial price inflation in the targeted market and financial instruments, be they stocks, junk bonds, real estate, foreign exchange, derivatives, etc. That same financial price instability, however, is what causes havoc with the real economies of countries—like those in southern Europe in recent years, in Asia in the late 1990s, Japan in early 1990s, and which led to the global financial crash of 2008-09 itself….

….Shadow banks generate profits from excess lending and debt creation, from financial speculation, and from creating financial asset bubbles that primarily benefit their wealthy investors….Shadow banks add little to the real economy or real economic growth. And in the process of generating excess financial profits for themselves and their finance capital elite, they destabilize economies and can often lead to major financial asset collapses, general credit crunches and at times even credit crashes, that in turn lead to deep recessions and prolonged, difficult recoveries….

….Shadow banks are the preferred institutions of the global finance capital elite. They always work to the benefit of that elite, often at the direct expense of the real economy, including non-financial businesses, and always at the expense of working classes who never share in the capital gains but pay the price in slower economic growth and repeated financial-economic crashes.

Recovery? No, Endgame

Since 2009 we have collectively told ourselves that recovery was underway, and this became the mainstream received wisdom. Optimism made a substantial return, even though it was, for insiders, tinged with desperation, and was grounded in the catabolic consumption of peripheral economies. Fears of deflation, which had been widespread during 2008/2009, receded again, and once again deflationist commentators were ridiculed. Commentators returned to speaking of inflationary risks, as they always do after a long enough period of upward momentum, given humanity’s proclivity for extrapolating current trends forward, and relative inability to anticipate trend changes, however obvious they may be if one is paying attention.

The supposed recovery is a temporary fantasy – a smoke and mirrors game grounded in ponzi finance on steroids. The excess claims to underlying real wealth, created during the both the initial boom and the false recovery, are set to evaporate once the extent of our crisis of under-collateralization become evident, and that moment is rapidly approaching. The deflation which was always the obvious endgame of credit expansion, is now underway and picking up momentum. A gigantic pile of IOUs is set to be defaulted upon, and the resulting monetary contraction will slash demand for almost everything, not for lack of desire to purchase or consume, but for lack of ability to pay for the privilege. This will undercut price support for almost everything many years.

As we wrote in 2011:

In the process of credit expansion, we borrow from the future through the creation of debt. Our focus on virtual wealth has very significant real world effects, as it distorts our decision-making in ways that guarantee bust will follow boom. We bring forward tomorrow’s demand to over-consume today, frantically building out productive capacity in order to satisfy that seemingly insatiable demand.

As money supply increase leads the development of productive capacity during this manic phase, increasing purchasing power chases limited supply and consumer prices rise. Increasing virtual wealth also drives up asset prices across the board, strengthening speculative feedback loops that inevitably strain the fabric of our societies, all too easily to the breaking point….

….Decades of inflation lie behind us. It is deflation – the contraction of the supply of money plus credit relative to available goods and services – that lies ahead….When a credit expansion reaches the point where the debt created can no longer be serviced by a hollowed-out real economy, and the marginal productivity of debt becomes negative, continued growth is no longer possible….

….The process of monetary contraction following a ponzi expansion is implosive because it involves the destruction of virtual value – the fairly abrupt realization that the emperor has no clothes….It is an economic seizure, and its effect is devastating. Credit in its myriad forms represents the vast majority of the money supply, and it is about to lose its money equivalency. This will leave only cash, and that cash will be extremely scarce. Aggravating the effect of crashing the money supply will be a substantial fall in the velocity of money, meaning that money will largely cease to circulate in the economy as people hang on to every penny they can get their hands on….

….Nothing moves in an economic depression. This is the polar opposite of the frenetic activity of the inflationary boom years. Instead of the orgy of consumption to which we have become accustomed, we will experience austerity on a scale we cannot yet imagine.

This is exactly what we are currently seeing places like Greece and Cyprus – the canaries in the coal mine. As much trouble as such places are currently in, however, this is still the thin edge of the wedge even for them. And for places as yet unaffected, the storm is rapidly approaching. Departures from reality can persist only so long as the illusions they are based on retain credibility:

Self-evidently, we are now in the cliff-diving phase, but unlike the bounce after the September 2008 financial crisis, there will be no rebound this time around. That is owing to two reasons. First, most of the world is at “peak debt”. That is, the ratio of total credit market debt to current national income ranges between 350% and 500% in every major economy; and that is the limit of what can be serviced even at today’s aberrantly low interest rates. As Milton Friedman famously observed, markets are ultimately not fooled by the money illusion. In this case, the illusion is that today’s sub-economic interest rates will last forever and that debt carrying capacity has been elevated accordingly. Not true. Short-term interest rates may be temporarily and artificially pegged at the zero bound by central bankers, but at the end of the day debt carrying capacity is tethered by real economics and normalized costs of money and debt. Accordingly, the central banks are now pushing on a string. The credit channel of monetary transmission is over and done. The only remaining effect of the residual level of money printing still underway is that ZIRP enables carry trade gamblers to drive financial asset prices ever higher, thereby setting up another thundering collapse of the financial bubbles being generated for the third time this century by the world’s central banks.

We are already witnessing the next phase of financial crisis, and the fear-based contagion is already spreading. However, as John Stuart Mill said in 1867, “Panics do not destroy capital; they merely reveal the extent to which it has been previously destroyed by its betrayal into hopelessly unproductive works.” A vast quantity of capital has been so betrayed during the era of monetary profligacy, mispricing and malinvestment that is now coming to an end, and the coming financial reckoning will reveal the extent of that destruction.

After the Commodity Blow-Off…

The monetary supernova sparked an orgy of consumption, fuelling an explosion of demand for commodities of all kinds and a frantic scramble to supply that demand. In the process, huge distortions were created from which considerable consequences will flow now that the blow-off phase is over:

The worldwide economic and industrial boom since the early 1990s was not indicative of sublime human progress or the break-out of a newly energetic market capitalism on a global basis. Instead, the approximate $50 trillion gain in the reported global GDP over the past two decades was an unhealthy and unsustainable economic deformation financed by a vast outpouring of fiat credit and false prices in the capital markets.For that reason, the radical swings in commodity prices during the last two decades mark the path of a central bank generated macro-economic bubble, not merely the unique local supply and demand factors which pertain to crude oil, copper, iron ore, or the rest….What really happened is that the central bank instigated global macro-economic bubble ripped commodity pricing cycles out of their historical moorings, resulting in a one time eruption of price levels that had no relationship to sustainable supply and demand factors in the mines and petroleum patch. What materialized, instead, was an unprecedented one-time mismatch of commodity production and use that caused pricing abnormalities of gargantuan proportions.

The erstwhile prolonged frenzy of consumption has created the sense that demand for commodities would be eternally insatiable, but that perception is now being profoundly shaken. It has long been clear that commodity demand would fall enormously during the coming period of deflation and depression, but the illusion of perpetual expansion has been slow to release its grip.

In the summer of 2011 we wrote that commodities were peaking and offered a bearish prognosis in Et tu, Commodities?. At the time this was seen as being quite heretical, as contrarian forecasts at peaks always are. Fear of shortages was rampant, but fear causes market participants to bid up the price in advance of what the fundamentals would justify, opening the door to a major price readjustment, as we saw in 2008. At the time, we explained the nature of commodity tops and what inevitably follows:

As an expansion develops, one can generally expect increasing upward pressure on commodity prices, thanks to both demand stimulation and latterly the perception that prices can only continue to increase. The resulting crescendo of fear – of impending shortages – is accompanied by the parabolic price rise typical of speculative bubbles, as momentum chasing creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. At the point where almost everyone with the capacity to do so has jumped on the bandwagon, and all agree that the upward trend is set in stone, a trend change is typically imminent.

We find ourselves still near the peak of the largest credit bubble in history. As faith in many of the more spurious ‘asset’ classes devised by ‘financial innovation’ has been shaken, faith in the ever increasing value of commodities has strengthened. However, commodities are not immune to the effects of a shift from credit expansion to credit contraction, despite justifications for endless price rises, such as the apparently bottomly demand from China and the other BRIC countries.

Every bubble is accompanied by the story that it is different this time, that this time prices are justified by fundamentals which can only propel prices ever upwards. It is never different this time, no matter what rationalizations exist for speculative fervour. BRIC demand only appears to be insatiable if we make our predictions solely by extrapolating past trends, but that approach leaves us blind to trend changes and therefore vulnerable to running off a cliff. Insatiable demand results from seemingly endless cheap credit, given that demand is not what one wants, but what one can pay for. When credit collapses, so will demand, and with it the justification for higher prices.

While credit expansion (inflation) is a powerful driver of increasing prices, credit contraction (deflation) is a far more powerful driver of decreasing prices. Credit, having no substance, is subject to abrupt fear-driven disappearance. Confidence and liquidity are synonymous….As contraction picks up momentum, the loss of credit will rapidly lead to liquidity crunch, drastically undermining price support for almost everything. With purchasing power in sharp retreat, however, lower prices will not lead to greater affordability. Purchasing power typically falls faster than price under such circumstances, so that almost everything becomes less affordable even as prices fall.

At the time we called it a peak that would stand for a very long time.

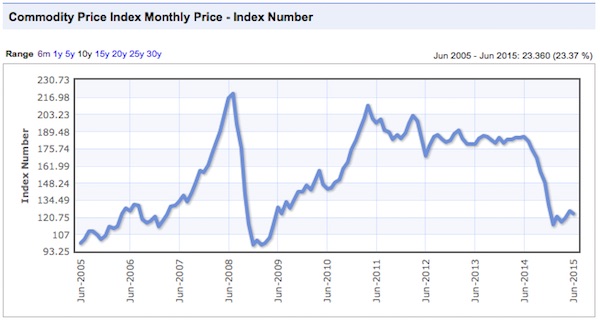

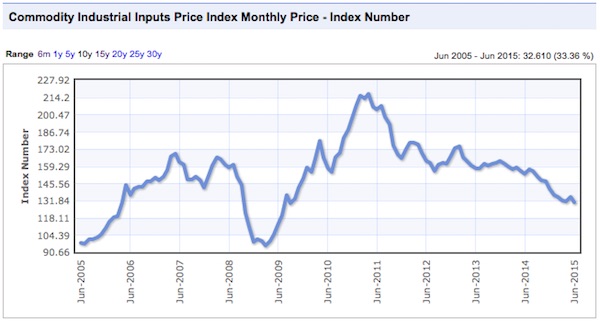

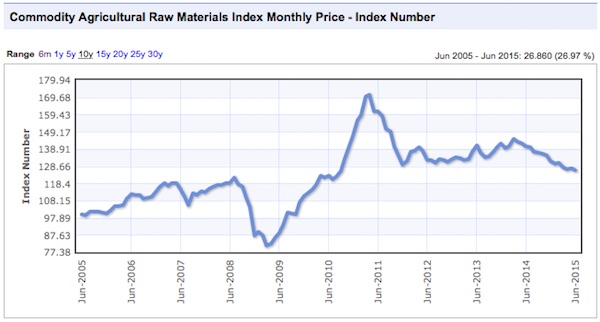

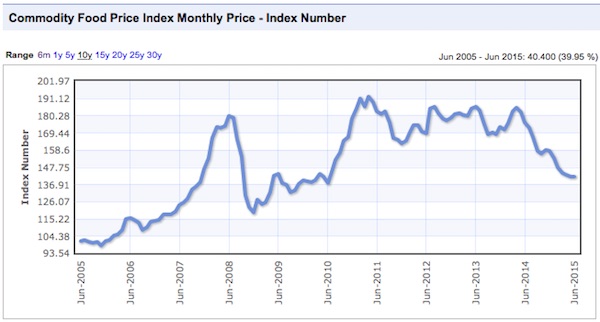

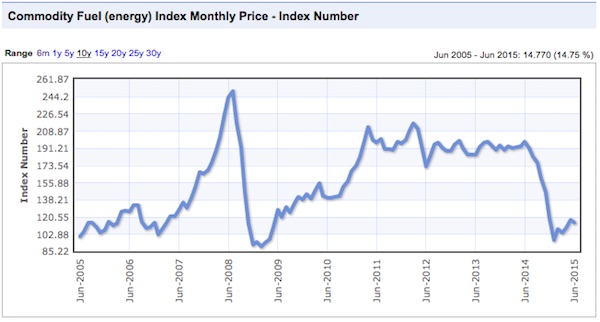

There were commodity peaks across the board in 2011, and despite the supposed on-going recovery from that time, price declines have continued.

Charts: indexmundi.com/commodities

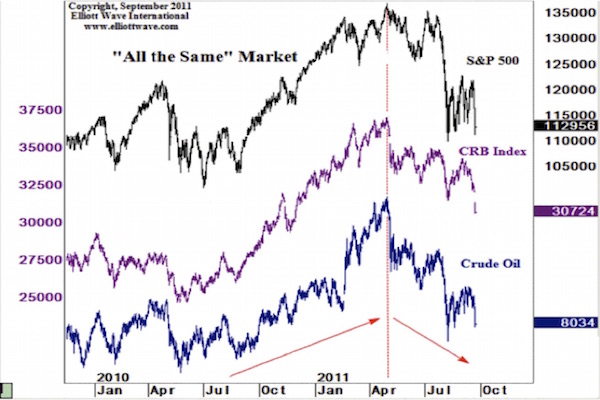

Tops in different asset classes can be remarkably co-incident. See for instance this graphic that we have shown before (thanks to Elliottwave.com), demonstrating the ‘All the Same Market” phenomenon with co-incident tops on the same day:

The dollar is now receiving additional upward propulsion from the Federal Reserve’s stated goal to raise interest rates, but this is almost certainly less of a factor than a flight to safety, which would occur even at lower rates if driven by sufficient fear. Since interest rates are a risk premium, low rates are a good indication that the asset in question is perceived to be a safe haven. As a flight to safety gets underway in earnest, we should see a flood of money into the USD in a climate of falling interest rates, perhaps even to the point of being marginally negative in nominal terms, at least temporarily. In a climate of extreme fear, investors will pay for the privilege of capital preservation, for so long as the illusion of it lasts.

Emerging markets, which have collectively borrowed $4.5 trillion USD are going to experience a tremendous squeeze, aggravating the consequences of their bust phase.

Had stockmarkets fallen more than 40% from their peak, the national news bulletins and the mainstream papers would be full of headlines about collapse and calamity….But this is one of the great bear markets. It may seem less important because few people are directly invested in commodities. But in terms of people’s daily lives, commodity prices are very important indeed. The Arab spring started as a response to soaring food prices in North Africa. Rising and falling prices act as a tax rise/cut for western consumers. For commodity producing nations, falling prices mean loss export earnings, lost jobs and currency crises.

Declining Fortunes

Emerging markets and commodity companies are caught in a global economic downdraft, following on from their years of extraordinary boom and consequent over-investment. That misallocation of capital, compounded by the leverage involved, has created an enormous overhang of productive capacity. The sunk costs create an incentive to continue producing and generate at least some revenue, even as a supply glut is already causing prices to collapse. This is a toxic dynamic for a highly leveraged sector, leading to downward spiral of excess inventory and a pancaking debt pyramid:

In the case of the global mining industries, CapEx by the top 40 miners amounted to $18 billion in 2001. During the original boom cycle it soared to $42 billion by 2008, and then after a temporary pause during the financial crisis, reaccelerated once again, reaching a peak of $130 billion in 2013. Owing to the collapse of commodity prices as shown above, new projects and greenfield investments have pretty much ground to a halt in iron ore, met coal, copper and the other principal industrial materials, but there is a catch.Namely, that big projects which were in the pipeline when commodity prices and profit margins began to roll-over in 2012, are being carried to completion owing to the sunk cost syndrome. This means that available, on-line capacity continues to soar. The poster child for that is the world’s largest iron ore complex at Port Hedland, Australia. The latter set another shipment record in June owing to still rising output in the vast network of iron mines it services——-a record notwithstanding the plunge of iron ore prices from a peak of $190 per ton in 2011 to $47 per ton a present.

In such a climate, commodity company valuations are very vulnerable. They have already fallen substantially, but considering the negative circumstances they face are far closer to their beginning than to their end, it seems highly unlikely that the decline will end any time soon. Talk of capitulation is extremely premature:

Sprott Asset Management’s Rick Rule is one of the smartest guys in the resource investing world — and one of the most reasonable — which has made his interviews of the past few years a little disconcerting. Along with the obligatory positive thoughts on the long-term value of gold and silver and the resulting bright future for the best precious metals miners, he always points out that the sector hasn’t yet endured a capitulation, where everyone just gives up and sells at any price, tanking prices and setting the stage for the next bull market.

Knowing that this kind of existential crisis is still out there has taken the fun out of buying ever-cheaper mining stocks, which of course has been Rule’s point. Just because something is cheap doesn’t mean it can’t get a lot cheaper before its bear market is done….

….Both metals are now below the production cost of most miners, whose shares are cratering on the prospect of some truly horrendous operating results in the coming year. Which sounds a lot like what Rule is describing.

Commodities priced below the cost of production for most producers is exactly what one would expect in a deflation, as a combination of supply glut and lack of purchasing power drastically undercut price support. Our long term forecast at TAE is for an undershoot proportionate to the scale of the preceding overshoot, meaning a price collapse at least down to the cost of the lowest cost producer. Under such circumstances, there would be no investment in the sector for many years – a long period of under-investment proportionate to the previous over-investment. The attempt to avoid the day of reckoning is only adding to the eventual pain:

And that’s where central bank enabled zombie finance comes in. Production cuts and capacity liquidations in virtually every materials sector are being drastically delayed by the continuing availability of cheap finance. So what “extend and pretend” really means is that prices and margins will be driven even lower than would otherwise be the case in the face of excess capacity. Stated differently, the correlate of zombie finance is flattened profits for an unusually prolonged period of time.Here’s the thing. During the central bank driven doubled-pumped boom, profits margins rose to historically unprecedented levels because scarcity rents were being captured by producers during most of the past 15 years. Now comes the era of gluts and unrents. The casino is most definitely priced as if scarcity rents were a permanent fixture of economic life——when they were actually a freakish consequence of the central bankers’ reign of bubble finance.

Vulnerable Commodity Exporters

Commodity exporting nations, which were insulated from the effects of the 2008 financial crisis by virtue of their ability to export into a huge commodity boom, are indeed feeling the impact of the trend change in commodity prices. All are uniquely vulnerable now. Not only are their export earnings falling and their currencies weakening substantially, but they and their industries had typically invested heavily in their own productive capacity, often with borrowed money. These leveraged investments now represent a substantial risk during this next phase of financial crisis. Canada, Australia, New Zealand, are all experiencing difficulties:

Known as the Kiwi, Aussie, and Loonie, respectively, all three have tumbled to six-year lows in recent sessions, with year-to-date losses of 10-15%. “Despite the fact that they have already fallen a long way, we expect them to weaken further,” said Capital Economists in a recent note. The three nations are large producers of commodities: energy is Canada’s top export, iron ore for Australia and dairy for New Zealand. Prices for all three commodities have declined significantly over the past year, worsening each country’s terms of trade and causing major currency adjustments.

South Africa and Brazil are similarly affected:

Brazil’s real plummeted to a 12-year low of 3.34 to the dollar, reflecting the country’s heavy reliance on exports of iron ore and other raw materials to China. The devaluation tightens the noose on Brazilian companies saddled with $188bn in dollar debt taken out during the glory days of the commodity boom.

Complacency has been rife in these ‘lucky countries’ which have tended to perceive natural limits as someone else’s problem and to regard themselves as impervious to systemic shocks:

This colossal collapse in wealth is symptomatic of the wider economic problem now facing Australia, which for years has been known as the lucky country due to its preponderance in natural resources such as iron ore, coal and gold. During the boom years of the so-called commodities “super cycle” when China couldn’t buy enough of everything that Australia dug out of the ground, the country’s economy resembled oil-rich Saudi Arabia….….While the rest of the world suffered from the aftermath of the global financial crisis, Australia’s economy – closely tied to China – appeared impervious, with full employment and a healthy trade surplus. However, a collapse in iron ore and coal prices coupled with the impact of large international mining companies slashing investment has exposed Australia’s true vulnerability. Just like Saudi Arabia, which is now burning its foreign reserves to compensate for falling oil prices, Australia faces a collapse in export revenue.

The greater the extent to which an exporting economy has placed all its eggs in one basket, the greater the vulnerability of its economy:

Australia’s export base has narrowed to levels approaching that of a “banana republic,” a former government adviser says, raising the specter of the country’s economic nadir almost 30 years ago.The concentration of shipments abroad is at the highest level in more than 50 years, according to Andrew Charlton, who counselled former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on economic policy. The nation’s budget is “hostage” to global iron ore prices, with a $10 drop taking up to A$10 billion from forecast revenue, he said. The global iron ore price has dropped more than $12 in the past month, further exposing Australia’s lack of export alternatives….….”Even some low-income countries like Nepal, Kenya, and Tanzania have greater export diversity than Australia.” His analysis again raises the question of what Australia will fall back on as the resources tide recedes. Exports have gone backwards as a proportion of the economy over the last 15 years in almost every non-resources industry, and services are now too small to offset mining.

Australia’s national business model has for a long time been ‘dig it up and sell it to China as quickly as possible’, but the success of the mining sector in its heyday caused a large appreciation of the currency (the Dutch Disease), which in turn damaged the international competitiveness of the country’s manufacturing base. Manufacturing was increasingly off-shored, hence the inability to revive it now that the currency is falling. Add to that the fact the global trade takes a major hit in times of economic depression, and it is obvious that alternative exports will struggle to pick up pace. In addition, so much of the focus of the domestic economy has come to centre around real estate during the development of its gigantic property bubble, that interest in out-sized profits from property speculation have easily outweighed interest in the normal profits one could expect from re-establishing manufacturing:

“Australian governments have been operating on the assumption that, once the mining boom passed, low interest rates and a falling dollar would be enough to bring the non-resource sectors dancing out of their graves,” Charlton, now director of consultancy AlphaBeta, said in a research report. “Unfortunately, no such resurrection is occurring.” “Australia watched idly as the rust-belt manufacturing suburbs around Sydney and Melbourne were transformed from red-brick factories into red-hot real estate,” he said.

Even erstwhile ‘rock-star economies’ are feeling the pressure to cut interest rates, in the vain hope that beggar-thy-neighbour currency devaluations will be beneficial:

Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand slashed borrowing costs for the second time in six weeks even as housing prices continue to skyrocket. A day earlier, its counterpart across the Tasman Sea (already wrestling with an even bigger property bubble of its own) said a third cut this year is “on the table.”Just one year ago, it seemed unthinkable that officials in Wellington and Sydney, more typically known for their hawkishness and stubborn independence, would join the global race toward zero. But with commodity prices sliding, China slowing and governments reluctant to adopt bold reforms, jittery markets are demanding ever-bigger gestures from central banks. Even those presiding over stable growth feel the need to placate hedge funds, lest asset markets falter. When this dynamic overtakes countries such as New Zealand (growing 2.6%) and Australia (2.3%), it’s hard not to conclude that ultra-low rates will be the global norm for a long, long time.

Contagious instability is spreading from the periphery towards the centre, threatening to convulse the financial world again, with considerable knock-on consequences in the real world:

Less than a decade after a housing/derivatives bubble nearly wiped out the global financial system, a new and much bigger commodities/derivatives bubble is threatening to finish the job. Raw materials are tanking as capital pours out of the most heavily-impacted countries and into anything that looks like a reasonable hiding place. So the dollar is up, Swiss and German bond yields are negative, and fine art is through the roof.

Now emerging market turmoil is spreading to the developed world and the conventional wisdom is shifting from a future of gradual interest rate normalization amid a return to steady growth, to zero or negative rates as far as the eye can see….Indeed, the major monetary powers that are easing — Europe, Japan, Australia and New Zealand — have all suggested rates may stay low almost indefinitely. Those angling to return to normalcy, meanwhile — the Federal Reserve and Bank of England — are pledging to move very slowly. Even nations with rising inflation problems, like India, are hinting at more stimulus….

….So…the central banks will panic. Again. Countries that retain some control over their monetary systems will see their interest rates fall to zero and beyond, while those that don’t will be thrown into some kind of new age hyperinflationary depression. Not 2008 all over again; this is something much stranger.

Stranger indeed, and a far more powerful contractionary impulse than in 2008. While ultra-low rates are characteristic of the current stage, as we stand on the brink, they are not likely to persist into the coming strongly deflationary environment rife with risk. While perceived low risk states may be able to maintain low rates for a while, others will not be so lucky as credit spreads blow out to form self-fulfilling prophecies. In any case, rates may appear low only in nominal terms. In a contractionary environment, where the real rate is the nominal rate minus negative inflation, real interest rates will be high and rising. This will compound the burden imposed by decades of over-leverage, for both companies and countries, to an enormous extent. Indebted ‘lucky countries’ are not going to look so lucky in a few years time.

China – Not Just Another BRIC in the Wall

More than anything, the story of both the phantom recovery and the blow-off phase of the commodity boom, has been a story of China. The Chinese boom has quite simply been an unprecedented blow-out the like of which the world has never seen before:

China has, for years now, become the engine of global growth. Its building sprees have kept afloat thousands of mines, its consumers have poured billions into the pockets of car manufacturers around the world, and its flush state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have become de facto bankers for energy, agricultural and other development in just about every country. China holds more U.S. Treasuries than any other nation outside the U.S. itself. It uses 46% of the world’s steel and 47% of the world’s copper. By 2010, its import- and export-oriented banks had surpassed the World Bank in lending to developed countries. In 2013, Chinese companies made $90-billion (U.S.) in non-financial overseas investments. If China catches a cold, the rest of the world won’t be sneezing – it will be headed for the emergency room.

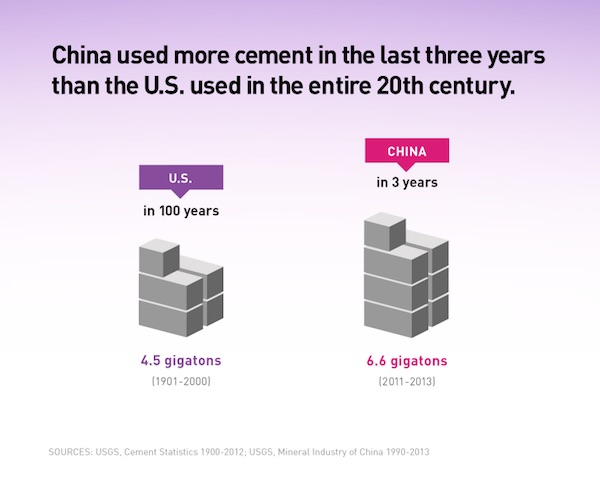

To put China’s construction bonanza in perspective, the country used more cement in 3 years than the USA used in the entire 20th century:

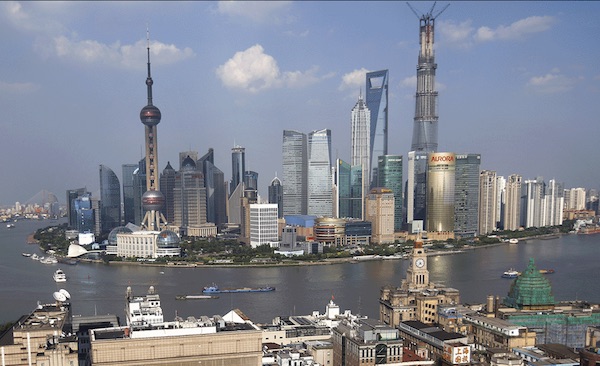

The setting is Shanghai’s financial district of Pudong, dominated by the Oriental Pearl Tower at left, and the new 125-story Shanghai Tower, China’s tallest building and the world’s second tallest skyscraper, at 632 meters (2,073 ft) high, scheduled to finish by the end of 2014. Shanghai, the largest city by population in the world, has been growing at a rate of about 10% a year the past 20 years, and now is home to 23.5 million people — nearly double what it was back in 1987.

Or look into China’s ghost cities, fully equipped with everything, except people:

The richest 70 members of China’s legislature added more to their wealth last year than the combined net worth of all 535 members of the U.S. Congress, the president and his Cabinet, and the nine Supreme Court justices. The net worth of the 70 richest delegates in China’s National People’s Congress, which opens its annual session on March 5, rose to 565.8 billion yuan ($89.8 billion) in 2011, a gain of $11.5 billion from 2010, according to figures from the Hurun Report, which tracks the country’s wealthy. That compares to the $7.5 billion net worth of all 660 top officials in the three branches of the U.S. government.

The income gain by NPC members reflects the imbalances in economic growth in China, where per capita annual income in 2010 was $2,425, less than in Belarus and a fraction of the $37,527 in the U.S. The disparity points to the challenges that China’s new generation of leaders, to be named this year, faces in countering a rise in social unrest fuelled by illegal land grabs and corruption. “It is extraordinary to see this degree of a marriage of wealth and politics,” said Kenneth Lieberthal, director of the John L. Thornton China Center at Washington’s Brookings Institution. “It certainly lends vivid texture to the widespread complaints in China about an extreme inequality of wealth in the country now.”….

….Rupert Hoogewerf, chairman and chief researcher for the Hurun Report, estimates that for every Chinese billionaire the company discovers for its list, there is another one it misses, meaning the gap between the wealth of China’s NPC and the U.S. Congress may be greater still. “The prevalence of billionaires in the NPC shows the cozy relationship between the wealthy and the Communist Party,” said Bruce Jacobs, a professor of Asian languages and studies at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. “In all levels of the system there seem to be local officials in cahoots with entrepreneurs, enriching themselves, and this has led to a lot of the demonstrations.”

China built like there was no tomorrow, thereby guaranteeing that there will not be for the country in its current form. The raw materials demand was simply staggering:

The torrid demand for commodities during this second wave resulted in part from the need to feed cement, steel, copper, aluminum and hydrocarbons into the maw of China’s massive infrastructure, high rise apartment and commercial building projects and similar construction booms in other emerging market economies. And on top of that was another whole layer of demand for the raw materials needed to build the ships, earthmovers, mining machinery, refineries, power plants and steel furnaces and mills that were directly embodied in the capital spending spree.Stated differently, the torrid demand for construction steel in China indirectly led to demand for more iron ore bulk carriers, which in turn required more plate steel to supply China’s shipyards which were given the contracts to build them. In short, a capital spending boom creates a self-feeding chain of materials demand——especially when its fuelled by cheap capital costs and the economically false rates of return embedded in long-lived capital assets funded by it.

While it is often referred to as an economic miracle, it will prove to be less of a dream and more of a nightmare as the credit hyper-expansion upon which it rests unravels. In July 2012, we described the situation in Meet China’s New Leader : Pon Zi. As the description implies, the boom was built on a massive expansion of credit and debt:

In the case of China, for example, public and private credit outstanding at the end of 2007 amounted to just $7 trillion or about 150% of its GDP. During the next seven years—-owing principally to Beijing’s maniacal stimulus of domestic infrastructure investment designed to replace waning exports——China’s now completely unhinged credit machine generated new debt equal to triple the 2007 amount, thereby bringing credit outstanding to $28 trillion or nearly 300% of GDP at present….

….Taken together, the combination of unprecedented financial repression in developed market capital markets and the prodigious expansion of domestic business credit in China and the emerging markets elicited a tidal wave of capital investment unlike the world has ever witnessed. This put a renewed round of pressure on commodities that caused a second surge of prices which peaked in 2011-2013….

….And therein lies the origins of the deflationary wave now rocking the global commodity markets. Neither the developed market consumer borrowing binge nor the China/emerging market infrastructure and industrial investment spree arose from sustainable real world economics.

They were artifacts of what history will show to be a hideous monetary expansion that left the developed market world stranded at peak household debt and the emerging market world drowning in excess capacity to produce commodities and industrial goods.

Shadow banking, outside of the formal banking system in the form of trusts, “wealth management products” and foreign-currency borrowings, lies at the heart of the Chinese ponzi scheme, as in the rest of the world, only in China it operates at a completely different scale and speed of expansion than elsewhere:

A study by JP Morgan Bank in 2012 estimated that the shadow banking sector in China grew from only several hundred billions of dollars in total assets under management in 2008, to more than $6 trillion by the end of 2012. In percentage terms, shadow banks assets accelerated 125% in just the second half of 2009, followed by another 75% growth in 2010. Shadow bank assets grew additional 35% and 33% in each of the two years, 2012-13. By 2013 the total had risen to more than $8 trillion, according to the research arm of Japan’s Nomura Securities company. Shadow bank total assets rose another 14% and $1 trillion in 2014—to more than $9 trillion….….At the center of shadow bank instability has been the so-called ‘Investment Trusts’. According to McKinsey Research, Investment Trusts today account for between $1.6-$2.0 trillion (of the roughly $9 trillion) of all shadow bank assets in China. Trusts’ assets grew five-fold between 2010 and 2013. Approximately 26% of the Trusts provided credit (and therefore generate debt) to local governments for infrastructure spending, another 29% to industrial and commercial enterprises, another 20% to real estate and financial institutions, and other 11% to investors in stock and bond markets. Local government debt in particular has risen by more than 70% in China since 2010. In other words, shadow bank credit has gone mostly to those sectors of China’s economy where debt has accelerated fastest and produced financial bubbles….

Fictitious, self-feeding private debt growth has become a dominant feature of the Chinese economy for far too long, causing enormous distortions in supply and demand for the pure purpose of continued credit expansion. There is no way that such a huge artificial stimulation of demand could fail to depress demand for almost everything in the years to come:

Zoomlion customers sometimes buy ten concrete mixers when they planned to initially by one or two. They have a perverse incentive to buy more than they need because these concrete trucks are purchased via finance packages supplied by Zoomlion. Then the machines can be garaged and used as collateral to borrow further funds from other lenders. Zoomlion continues to grow while cement sales have plunged. In May, cement output increased 4.3% YoY, down from 19.2% recorded last year. Zoomlion’s new debt of $22.5B buys roughly 900,000 trucks which could produce enough concrete (at six loads a day) to build over thirty Great Pyramids of Giza a day.Every sector is infected with these kinds of perverse business practices, steel traders used loans meant for steel projects to speculate in property and stocks, it has been common (apparently) for steel traders to secure loans to buy steel then use this same steel as collateral to borrow funds to invest in property development and the stock market. In many ways this is the steel version of the Zoomlion model.

Lending through the formal banking system is restricted by government’s vain attempts to restrict credit expansion:

During the past two years, 2013-2014, a struggle has been underway between China and its shadow banks….In spring 2013, China tried to slow the asset price bubbles by making loans more expensive, by raising general economy-wide interest rates. That had unintended, counterproductive effects, however. It quickly resulted in a credit crunch that slowed the entire economy almost. Unable to get loans from China’s traditional banks, local governments attempting to continue the infrastructure boom borrowed even more from the shadow banks. Bubbles in housing and infrastructure grew further.

The growth of shadow banking as a means to evade such limits has been greatly enhanced as a result, illustrating the lack of control central governments actually exert of financial expansion and contraction. Where official restrictions exist, credit expansions will find a way to happen anyway, as they have throughout history.

Local government is an extremely important player in the infrastructure boom, and consequently in the accumulation of debt, despite persistent central government attempts to rein them in :

Local governments in China take almost exclusive responsibility for urban infrastructure investments and financing. In 2011 China invested the equivalent of 12.5% of GDP in fixed assets for public utilities, infrastructure and facilities. More than 80% of this was sponsored by local governments and their entities. China’s Budget Law imposes strict restrictions on the borrowing powers of local governments. To circumvent this law, local governments have set up around 10,000 Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) to issue debt and finance infrastructure investment. Local government borrowing rose sharply to finance stimulus packages in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. By the end of June 2013 the explicit debt load of local governments amounted to RMB 10.9 trillion; local government guaranteed debts, RMB 2.67 trillion; and other contingent debts, RMB 4.3 trillion, with the total around 33% of GDP.

The side-stepping of central government credit control mechanisms has turned local government into a major engine of shadow banking expansion, complete with implicit guarantees that reduce apparent risk despite the dubious nature of many infrastructure projects:

Beijing has tried to contain local-debt growth since at least 2010. But according to IMF estimates, local-government debt reached 36% of GDP in 2013, double its share of GDP in 2008, and will increase to 52% of GDP in 2019. Since the mid-1990s, after some local governments went on borrowing binges to build hotels and golf courses, the central government has banned city halls from selling bonds or borrowing directly from banks. Instead, localities borrow indirectly through so-called local-government-financing vehicles. These entities raise money for local governments to fund roads, subways, airports, housing sites and other projects. Local governments implicitly guarantee the debt, helping the financing firms borrow no matter whether projects make sense.

The exponential growth in the shadow banking in China has been so rapid that in a very few years it has begun to strain the country’s ability to service that debt:

Booming shadow banking growth has pushed China to the outer limits of its ability to keep its economy functioning smoothly. With total leverage in the Chinese economy now topping 280% of gross domestic product, it was clear that credit quality was deteriorating, Primavera Capital Group founder and chairman Fred Hu told delegates at a Fung Global Institute forum….Debt sustainability, the ability to service debts, is a key measure of solvency. Analysis by the McKinsey Global Institute earlier this year showed debt in the Chinese economy had roughly quadrupled between 2007 and the middle of last year to US$28 trillion, leaving it with a debt-to-GDP ratio more than twice that of crisis-wracked Greece.

Authorities recognize the existence of the shadow banking, but, as is the case in the rest of the world, completely fail to understand its significance in terms of systemic risk:

Liu Mingkang, the former chairman of the China Banking Regulatory Commission, told the same forum that time was running out for the government to reform the financial system and liberalise credit markets sufficiently to obviate the need for shadow banking, though he was sanguine on the systemic risks posed….He added that shadow banking must be regarded by policymakers only as a short-term mechanism through which time can be bought to help finance small and medium-sized private enterprises until wholesale reform can be completed to liberalise access to capital markets and bank credit.

Shadow banking is no temporary measure without consequences. It represents a massive build up in unrepayable debt that is already beginning to act as a millstone round the neck of the Chinese economy and will continue to do so for many years, as the momentum towards debt default and economic contraction picks up further. This will be aggravated by the nature of the private debt created during the expansion:

A good deal of that private debt explosion has also taken the form of dangerous short term debt that requires frequent ‘roll over’ and refinancing. By 2014 a third of all new debt created in China was ‘roll over’ refinancing of prior debt. That means that should interest rates rise too far or too fast, many businesses heavily indebted to shadow banks will not be able to roll over that debt, and will have to default. In turn, defaults could result in panic sell offs of financial securities, followed by a general ‘credit crunch’ that will slow the real economy still faster than even at present.

In addition, the debt to GDP ratio is actually far worse than it appears, since GDP is substantially overstated:

During the course of its mad scramble to become the world’s export factory and then its greatest infrastructure construction site, China’s expansion of domestic credit broke every historical record and has ultimately landed in the zone of pure financial madness. To wit, during the 14 years since the turn of the century China’s total debt outstanding–including its vast, opaque, wild west shadow banking system—soared from $1 trillion to $25 trillion, and from 1X GDP to upwards of 3X.

But these “leverage ratios” are actually far more dangerous and unstable than the pure numbers suggest because the denominator – national income or GDP – has been erected on an unsustainable frenzy of fixed asset investment. Accordingly, China’s so-called GDP of $9 trillion contains a huge component of one-time spending that will disappear in the years ahead, but which will leave behind enormous economic waste and monumental over-investment that will result in sub-economic returns and write-offs for years to come. Stated differently, China’s true total debt ratio is much higher than 3X currently reported due to the unsustainable bloat in its reported national income.

Nearly every year since 2008, in fact, fixed asset investment in public infrastructure, housing and domestic industry has amounted to nearly 50% of GDP. But that’s not just a case of extreme of growth enthusiasm, as the Wall Street bulls would have you believe. It’s actually indicative of an economy of 1.3 billion people who have gone mad digging, building, borrowing and speculating.

The leverage that lifted China so high during the boom will crush it without mercy during the bust. Already, declining marginal productivity of debt is a major problem, meaning that it takes more and more debt to generate ever smaller additions to the over-stated GDP:

China has now become an “economy that is actually worth a lot less than they pretend it’s worth,” Ms. Stevenson Yang says. By her estimate, 60 to 70% of new lending is now going to service old debt. In 2006, $1.20 in new credit could stoke $1 in economic growth. Today, it takes over $3. At that rate, it takes a greater than 20% annual expansion in credit to sustain China’s target 7.5% economic growth. “That just means that the problem itself is getting bigger,” said Jonathan Cornish, managing director for Asian operations at Fitch Ratings.

The bust is already underway despite doomed government attempts to prevent it:

China’s stocks tumbled, with the benchmark index falling the most since February 2007, amid concern a three-week rally sparked by unprecedented government intervention is unsustainable. The Shanghai Composite Index plunged 8.5% to 3,725.56 at the close, with 75 stocks dropping for each one that rose. PetroChina Co., long considered a target of state-linked market support funds, tumbled by a record 9.6%. The rout dented investor confidence from Hong Kong to Taiwan and Indonesia, helping send the MSCI Emerging Markets Index to a two-year low.Monday’s retreat shattered the sense of calm that had fallen over mainland markets last week and raised questions over the viability of government efforts to prop up prices as the economy slows….“Investors are afraid the Chinese government will withdraw supporting measures from the market,” said Sam Chi Yung, a strategist at Delta Asia Securities Ltd. in Hong Kong. “Once those disappear, the market cannot support itself.”

Government action cannot prevent over-valued markets from crashing. It did not work in the 1930s, and it will not work now. Temporary postponement was all that intervention could achieve, and as always, that postponement came at a price, guaranteeing that the inevitable crash will be worse when it does occur. Central banks are not omnipotent. They may appear to be during an expansion when everything is going in a direction people are happy with, so no one asks difficult questions, but during a contraction that they cannot prevent, their powerlessness will become blindly obvious.

The Chinese government is currently attempting to conceal the extent of the accelerating contraction, but official figures are meaningless. Looking behind the scenes makes it clearer why the contagion from China is spreading a wave of deflationary deleveraging across so many sectors globally:

Much of the economic weakness rippling through emerging markets is “made in China”. A slump in Chinese investment growth has hammered global demand for commodities and some manufactured products, triggering a chain reaction that is depressing emerging market exports, deepening deflationary pressures and even sapping consumer demand….

….The magnitude of China’s investment slump this year is likely to have been much greater than official figures show. Beijing’s official monthly data series tracks “fixed asset investment” (FAI), which grew by 11.4% year on year in June — not the sort of figure that might be expected to elicit alarm. But FAI readings are inflated by several elements — such as sales of land and other assets — that do not add to the country’s productive capital stock. A cleaner measure of how much companies are investing in boosting their productive capacities — and therefore in their futures — is gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), which strips out extraneous items to capture capital goods deployment. By this yardstick, investment is tanking….When viewed from this perspective, China’s slumping demand for iron ore, copper, alumina and other commodity imports from Latin America, Africa and elsewhere is easier to comprehend.

….Local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) — key agents of infrastructure investment at the grassroots level — are reaping an average return on assets on infrastructure projects of around 3%, compared with an average interest rate on loans of around 7%.

Warnings regarding Chinese banking instability and the inevitability of a crash are being made, but remain relatively rare and generally go unheeded even in the face of considerable evidence.

In a country where the banks, even the largest, are not known for openness, Charlene Chu has warned since 2009 about a rapid expansion in lending that has seen something close to $15 trillion (£9.1 trillion) of credit created, fuelling a property and infrastructure boom that has no equal in history.To say her warnings have been unusual is to underestimate quite how important her contributions have been. Chu has explained the creation – from a standing start just five years ago – of a shadow banking industry in China that today is responsible for as many loans in terms of volume as the country’s entire mainstream financial system. Speaking for the first time since her departure from Fitch last year, Chu, who has taken a new job at Autonomous, the respected independent research firm, says she remains adamant that a Chinese banking collapse of some description remains not just an outside chance, but a certainty. “The banking sector has extended $14 trillion to $15 trillion in the span of five years. There’s no way that we are not going to have massive problems in China,” she says.

The inevitable systemic banking crisis will be compounded in its impact by the inevitable contraction of the real economy, with China taking the lead in both areas. It will be a world of knock-on consequences and of cascading system failure. See for instance the excellent example of the Chinese steel industry, which is set not only to collapse domestically, but to propagate economic contraction globally.

Nowhere is this more evident than in China’s vastly overbuilt steel industry, where capacity has soared from about 100 million tons in 1995 to upwards of 1.2 billion tons today. Again, this 12X growth in less than two decades is not just red capitalism getting rambunctious; its actually an economically cancerous deformation that will eventually dislocate the entire global economy. Stated differently, the 1 billion ton growth of China’s steel industry since 1995 represents 2X the entire capacity of the global steel industry at the time; 7X the size of Japan’s then world champion steel industry; and 10X the then size of the US industry.

Already, the evidence of a thundering break-down of China’s steel industry is gathering momentum. Capacity utilization has fallen from 95% in 2001 to 75% last year, and will eventually plunge toward 60%, resulting in upwards of a half billion tons of excess capacity. Likewise, even the manipulated and massaged financial results from China big steel companies have begin to sharply deteriorate. Profits have dropped from $80-100 billion RMB annually to 20 billion in 2013, and are now in the red; and the reported aggregate leverage ratio of the industry has soared to in excess of 70%.

But these are just mild intimations of what is coming. The hidden truth of the matter is that China would be lucky to have even 500 million tons of annual “sell-through” demand for steel to be used in production of cars, appliances, industrial machinery and for normal replacement cycles of long-lived capital assets like office towers, ships, shopping malls, highways, airports and rails. Stated differently, upwards of 50% of the 800 million tons of steel produced by China in 2013 likely went into one-time demand from the frenzy in infrastructure spending.

Indeed, the deformations are so extreme that on the margin China’s steel industry has been chasing its own tail like some stumbling, fevered dragon. Thus, demand for plate steel to build dry bulk carriers has soared, but the underlying demand for new bulk carrier capacity was, ironically, driven by bloated demand for the iron ore needed to make the steel to build China’s empty apartments and office towers and unused airports, highways and rails.

In short, when the credit and building frenzy stops, China will be drowning in excess steel capacity and will try to export its way out— flooding the world with cheap steel. A trade crisis will soon ensue, and we will shortly have the kind of globalized import quota system that was imposed on Japan in the early 1980s. Needless to say, the latter may stabilize steel prices at levels far below current quotes, but it will also mean a drastic cutback in global steel production and iron ore demand.

And that gets to the core component of the deformation arising from central bank fueled credit expansion and the drastic worldwide repression of interest rates and cost of capital. The 12X expansion of China’s steel industry was accompanied by an even more fantastic expansion of iron ore production, processing, transportation, port and ocean shipping capacity.

This is only one industrial sector, but the picture painted applies to many others. The flawed state development model in China, like the Japanese counterpart which preceded it in the 1980s, led to credit explosion and consequent mal-investment in over-production on a grand scale. As with Japan, painful consequences will follow, but this time the impact will be truly global.

Caofeidian lies a three-hour drive east of Beijing, a Chinese industrial dream jutting into the sea. A decade ago, it was a pretty coast whose shallow waters were dotted with fishing vessels. Today, it’s a manufacturer’s paradise in the making, its eight-lane roads connecting sprawling factories to a vast port. Named after a former imperial concubine, it was a place of feverish fantasy, where borrowed money fuelled a vast reclamation effort to create 200 square kilometres of land and build something new….….But the loans that allowed all that spending have just 50% odds of being paid back, says an independent research group that has spent years studying Caofeidian. The stakes are enormous. Caofeidian was a project of national importance for China, a “flagship,” according to Jon Chan Kung, chief researcher at Anbound, a Beijing think tank. “If this project fails, it proves that the major model driving China’s development has also failed.”

A New World Disorder

Our long global boom stands on the brink of a major reversal, the consequences of which will ricochet around the world as the credit pyramid pancakes. The endgame of a monetary supernova is credit implosion, and it does not play out as a slow squeeze. We are going to see some dramatic movements in the financial world, followed by a cascade of similarly dramatic events in the real economy, in the not too distant future. The process begins with the deflation that is already underway, with monetary contraction that leads to falling prices across the board, crushing companies and countries along the way and leading straight into economic depression.

Deflation and depression are mutually reinforcing, meaning the downward spiral will continue for many years. We have been warning about this dynamic since 2008, and have already seen the liquidity crunch start to play out in many parts of the world. Once it hits critical mass, and it can do so very quickly, momentum will increase greatly. China is the biggest domino about to fall, and from a great height as well, threatening to flatten everything in its path on the way down. This is the beginning of a New World Disorder…