There was not much good news from China last night, particularly as there were no PMI releases to allow the media and economists to project uncorrelated optimism. Everything from industrial production to retail sales came in under “estimates”, with industrial production in October particularly worrisome as the second worst month (only better than August) since 2008 and the depths of the Great Recession; meaning that there really hasn’t been a rebound in IP as anticipated by all those sunny PMI-based projections.

To go along with the growing manufacturing misery, electricity output fell 1.9% Y/Y in October and factory gate prices fell a rather sharp 2.2% representing the 32nd consecutive monthly decline. That would seem to suggest a manufacturing slump, that is “gaining” in deceleration, going back to the early/middle part of 2012.

Despite that rather obvious pattern being replicated all over the world, commentary continues to contain China’s obvious economic decline to its own domestic imbalances.

Weak domestic demand and a slumping real-estate market weighed on China’s industrial production, investment and retail sales in October, signaling more headwinds for the world’s second-largest economy. [emphasis added]

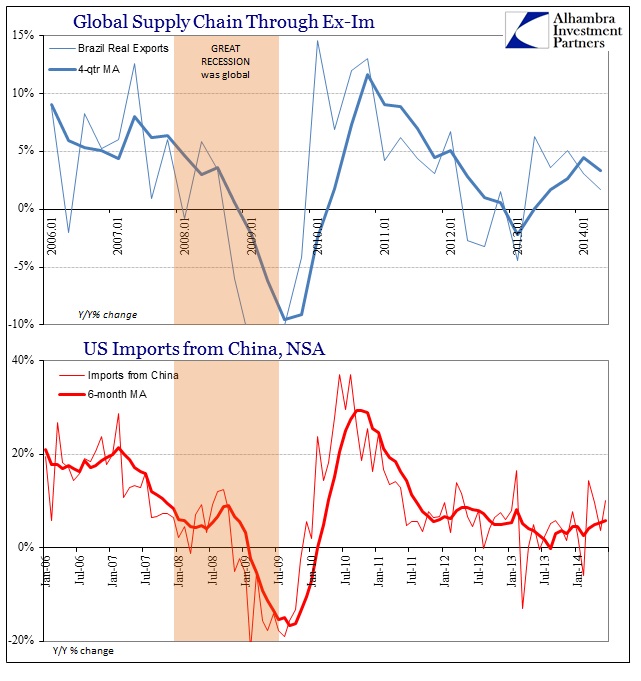

The only way that makes any comprehensive sense is if you ignore how China’s industrial production is following almost exactly US import activity from China (and how that effects Brazil and economies further down the line). That isn’t to say that the Chinese domestic economy is unimportant or actually a bright spot, but rather that the baseline cause of all this mess starts and ends with the lack of recovery (further faltering) in the US and Europe.

As with all things of this nature, central banks have simply buried that baseline under a sea of monetarism, or what would fairly be called bubbles. The housing imbalance in China was “nurtured” as means to introduce “stimulus” to combat the lack of demand from the US. That has never been resolved and now the PBOC is stuck trying to manage its own highly precarious housing bubble against a global recovery that not only never came but threatens further declines. To that end, they are “forced” to far more modest monetary projection to somehow not exacerbate the bubbles while at least trying to convince economic agents that there is still “stimulus” to be had. In that sense, it seems as if the PBOC and other central banks have had little difficulty in threading that needle at least with economists if not anyone else, as this significant change in central bank options seems to have eluded them and pretty much all media commentary.

The numbers Thursday, which showed slowing growth in all three categories and which missed analysts’ forecasts, follow stepped-up spending and an easier monetary policy in recent weeks as Beijing attempts to cushion the impact of the slower growth…

“It seems the fourth quarter has started with clear downward pressure on the economy,” said Crédit Agricole CIB economist Dariusz Kowalczyk. “So policy makers probably need to do more. We’ll probably see more policy easing on the monetary front.” [emphasis added]

From the same WSJ article:

Economists said the weak October numbers coupled with low inflation increase pressure on Beijing to ease monetary policy. Possible moves include a cut in the reserves that banks maintain with the central bank, lower interest rates charged by the central bank when lending to financial institutions and greater liquidity through the use of medium-term lending facilities.

Unless the PBOC rejects its own evolution, a reduction in the RRR and more “floods” of “reserves” are totally off the table.

This is, however, just blatant posturing that is highly misleading given the context:

Central-bank relending mechanisms also sought to make borrowing easier for the agriculture sector and smaller companies. “Beijing turns on the money and project spigots,” Bank of America Merrill Lynch said in a report. [emphasis added]

From Bloomberg on the same topics (China’s slowing growth):

“The data highlights downward pressure,” said Dariusz Kowalczyk, senior economist at Credit Agricole SA in Hong Kong. “It will encourage further monetary easing.” [emphasis added]

At least there is some recognition of the operational shift at the PBOC:

“The real estate sector remains a drag on the economy,” Louis Kuijs, Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc’s chief Greater China economist in Hong Kong, wrote in a note. “We expect the policy stance to remain supportive of growth, by stimulating infrastructure investment and urbanization, further relaxing of property market policies and taking more ‘targeted’ monetary easing steps.” [emphasis added]

At what point do we stop calling all of this “stimulus?” Stock markets rise on the promise of such “stimulus” but without awareness (or that “investors” simply don’t care) of why it may be needed in the first place. And since the presence of “stimulus” is not new, having been a full feature of the economic landscape for seven years, the decay in economic activity is in spite of all this past “stimulus.” That would suggest, under more normal and intuitive senses outside, apparently, of the “science” of economics, that such stimulus doesn’t really stimulate, and certainly not in the manner everyone seems to believe (a sustainable recovery that is fully different than temporary bursts of activity that represent nothing more than transitions from bad to worse).

There is not enough space here to list all the global “stimulus” initiatives taken just since 2012, chief among them QE3 and QE4 in the US. Despite all of them, that 2012 slowdown baseline remains unperturbed all over the entire world.