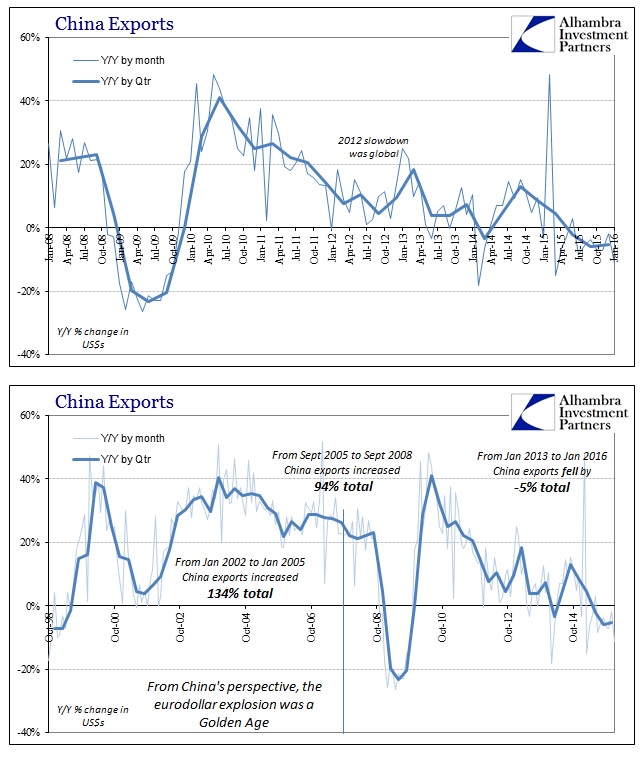

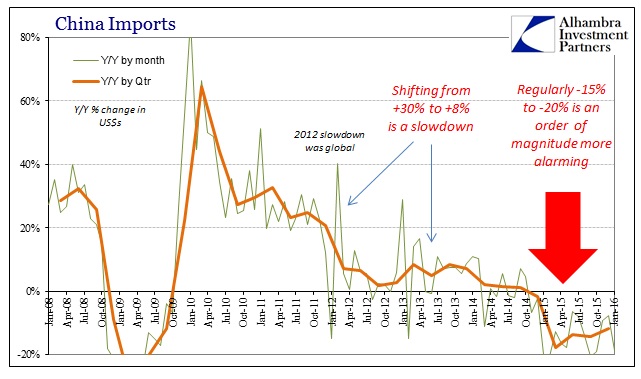

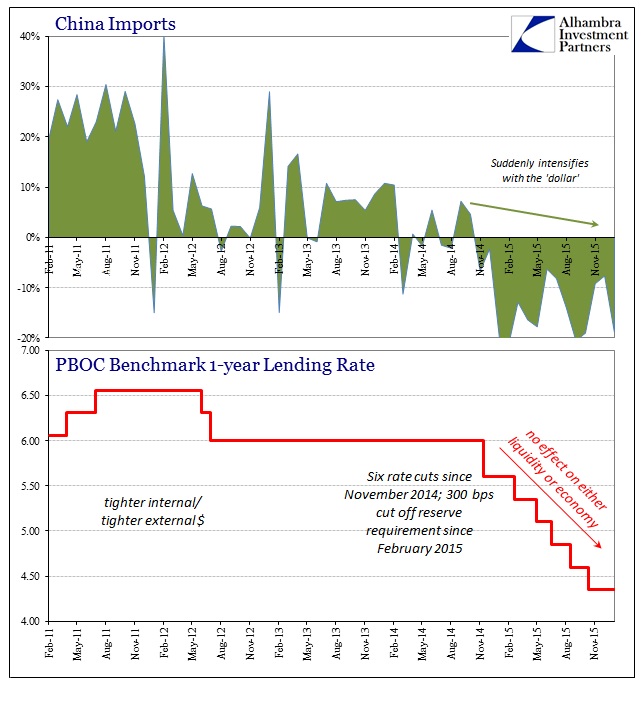

Last month when China’s exports “only” declined by 1.7% (revised) the entire orthodox world took it as a definitive signal for the long-awaited monetary stimulus effects. Whether it was the yuan’s “devaluation” or the six rate cuts and the often double shots of reserve requirement reductions that accompanied them, December trade figures were so very encouraging. Economists, in particular, were quick to convince themselves of their faith in monetarism, as exports for January then were expected to “only” slide by 1.9%, similar to December, while imports were predicted to be almost flat – an unbelievable improvement given that imports had been contracting regularly by 15%-20% throughout most of 2015.

As it turns out, these expectations for the turnaround were literally unbelievable since the latest trade figures from China were nowhere near them. Instead, both exports and imports collapsed yet again as if December’s monthly variation was only that. Exports dropped by 11.2% in January, the worst since March 2015 and the third worst of the “cycle.” Imports fell by 18.8%, more in line with last year’s baseline and nothing like a turnaround or even the hint of one.

The slide in exports suggests the yuan’s depreciation since August has yet to result in a sustained boost to the competitiveness of China’s factories. While the decline in shipments to and from most major destinations raises concern of a lingering trade slowdown, the readings may also be influenced by the timing of China’s week-long Lunar New Year holiday and volatility in trade flows with Hong Kong.

“Taken at face value these numbers are a negative sign for the Chinese economy,” said Shane Oliver, head of investment strategy at fund manager AMP Capital Investors Ltd. in Sydney. “But Chinese economic data is traditionally very volatile around January reflecting the floating timing of the Chinese new year and they may also reflect a correction to possible over-invoicing and disguised capital outflows that could have boosted the December data.”

The above quoted passage is exactly why economists keep getting it all wrong, in China and everywhere else. This is nothing like a “slowdown” (how could -20% imports be classified as that?) particularly since Chinese trade has been declining precipitously for over a year. Yet, despite the unusual clarity of direction and intensity, economists still time after time ignore it in favor of central bank activity that they are absolutely sure will create the desired effects even though nothing done so far has.

Consider that total exports in January 2016 were 5.1% less than exports in January 2013 and an astounding 14.1% below January 2014 (and all that snow). As bad as that is for both China and what it represents about the global economy, imports have simply collapsed; imports in January 2016 were 28% below January 2013 and a stunning 35% less than January 2014. They were even 7% less than January 2012, which is a very consistent suggestion as to the gathering global recession already being experienced in so many resource nations.

The implications are quite severe. China was built, financially and physically, to grow in trade by multiples of even what persisted from 2012 through 2014. If all that debt-financed capacity was cause for “reform” at 8% export growth, what happens to Chinese debt markets and its economy at -11%? This is easy math particularly when it is already being displayed and has been in effect for quite some time already. The import side is just a reflection of that export side dynamic plus the internal bubbles (all synced now into full reverse).

Despite all evidence otherwise, there remains this steadfast devotion to especially the PBOC as if it were the perfect expression of monetary power. The Chinese economy continues to slide toward oblivion, but economists are always sure that the “next one” of whatever central bank coloring will somehow turn out different than all the others. That’s what makes this expectation so confusing, because it is plain evident that nothing the PBOC (as any central bank) has done has had any impact. At least in Europe and Japan their respective central banks have appeared shifting to something else (laughably, but at least they make the effort toward “different” marketing of themselves) but the PBOC is caught instead in a loop of rerun monetary programs – and still economists expect them to lead to different results.

There were, in addition to the rate and reserve cuts, fixing in money markets after five months of fixing in CNY against the dollar, only to see more fixing in money markets and since the middle of January yet again fixing in CNY. To accomplish all that required untold and unquantifiable wholesale actions that have produced nothing but more turmoil for whatever small pockets of quiet and order. Even in the traditional, 1950’s view of the global monetary system, the Chinese have been “selling UST’s” which has accomplished no arresting of this negative economic baseline that stretches back not coincidentally to the “dollar’s” ugly rising in the middle of 2014.

By any rational count, there is nothing unexpected about what is happening in China. Even on exports there should have been more caution as the Census Bureau reported a 6.2% decline in US imports from China in December. Whether that suggests Hong Kong data and dollar fudging doesn’t really matter, as the signal from US “demand” is as negative as all the rest. What is being confirmed in China goes for the rest of the global economy, that the direction remains negative and maybe even highly so in far too many places but more importantly there isn’t anything any monetary policy can do about it. The PBOC is just as ineffective as all the rest; 2015 had the effect of effectively displaying the impotence.

If you believe that central banks are powerful and righteous in their intents, then you will be constantly surprised by the negativity. That was the state (denial) of some markets for some time, but most markets have finally surrendered at least to the possibility if not yet decided upon the fullest consequences of it.