By Tyler Durden at ZeroHedge

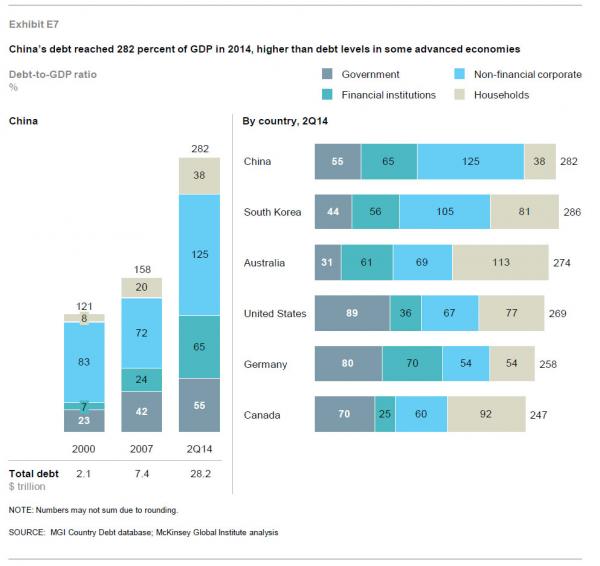

Ever since 2010 we have explained that one of the biggest risks facing the world is China’s gargantuan mountain of debt, seen in its consolidated state in the following McKinsey chart…

… a mountain which has doubled from its 2007 levels of 158% of GDP and which as of Q4 2015 is well over 300%, as China races to catch up with world-record holder Japan and its 400%+ total debt/GDP.

As we have also explained repeatedly, the problem with China’s debt load is that while it was China’s historic leveraging spree in the years of the great financial crisis, the world’s most populous nation, where debt has been rising exponentially, appears to be approaching its debt capacity load, and as such when the developed (and emerging) world slides into its next recession, there will be no “growth dynamo” which can add trillions in new debt to kick start world growth once more.

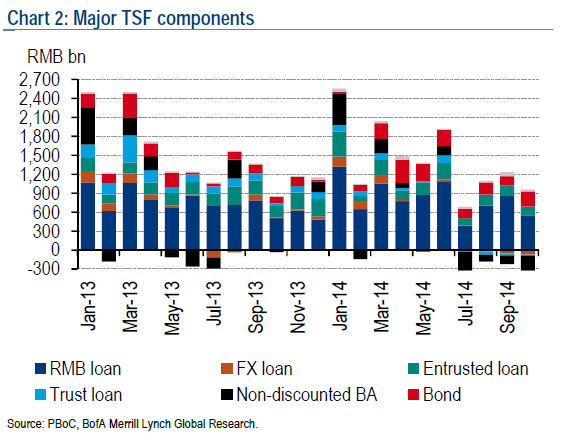

Another problem with China’s financial system is that in mid/late 2014, Beijing decided to implement a purge of the country’s shadow banking system, where “anything used to go”, and which while long overdue resulted in the shuttering of one of the country’s most permissive lending channels and led to a dramatic slowdown in the non-loan growth of China’s Total Social Financing, its broadest consolidated monthly credit creation tracker. The immediate result was the global growth swoon from the winter of 2014 which was incorrectly blamed on “harsh weather.”

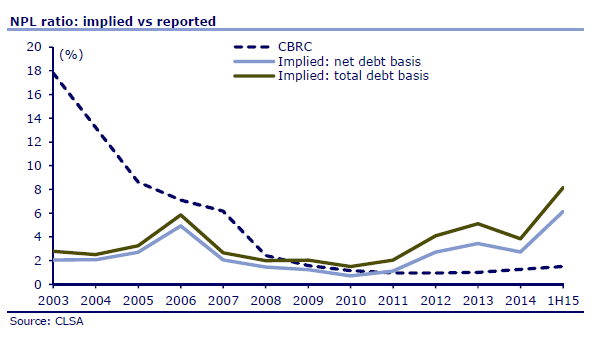

Yet another problem is that as commodity prices tumbles, as global trade slowed down, Chinese loan issuers have seen a massive surge in bad loans, if not officially, then certainly as tracked by unofficial sources. As we reported a month ago, China’s true NPL may be as high as 20%, a number suggesting up to $3 trillion in loans have gone bad and have to be written off. Even a far more conservative estimate by CLSA quantified China’s bad loans at 8.1%, five times greater than the official number and a key reason for China’s relentless deposit flight as local savers gradually realize a broad financial sector crisis is not only inevitable but just a matter of time.

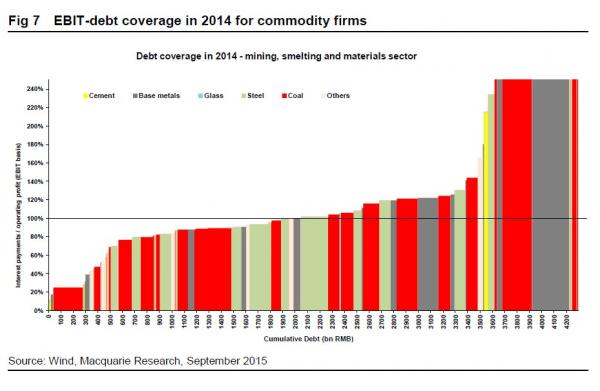

As debt loads rose and as interest expense built up, China’s companies were forced to keep generating ever more cash flow to satisfy creditors’ demands. However, as we also showed three months ago, as of this moment over half of China’s commodity firms are unable to even make one cash coupon payment.

Of course, in any normal society, this would be where dozens of management teams, seeing an insurmountable debt load, simply threw in the towel and filed for bankruptcy handing over the equity keys to the creditors. However, in China, where conventional Chapter 7/11 process is non-existent (the country only had its first ever corporate default recently) this is not an option as a wave of bankruptcies would be inevitably accompanied by the one thing Beijing dreads most: mass layoffs, and social unrest.

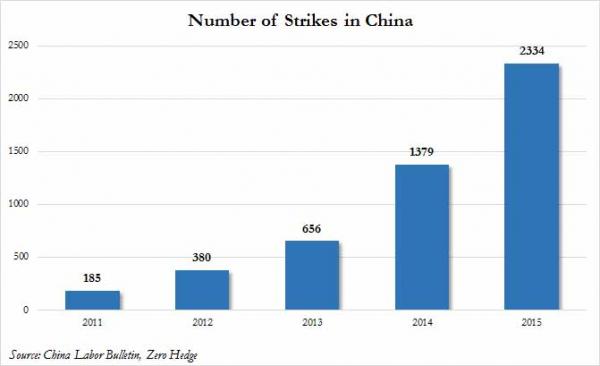

As a reminder, over a month ago we showed “The Biggest, And Most Underreported, Risk Facing China“, namely rising worker anger, manifested by a record surge in labor strikes, .

The real-time tracker we presented was quickly used by both the NYT and the WSJ to pen comparable articles of their own.

Beijing is quite aware of this confluence of financial and social instability and is desperate to if not halt it then delay it as much as possible.

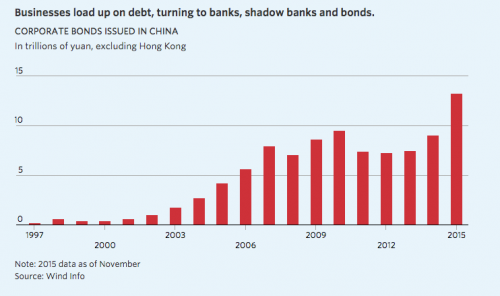

This delay, however, has a cost and as Caixin writes, the country’s banks – all of which are directly or indirectly state-owned – extended 11.1 trillion yuan in new loans in the first 11 months of the year, breaking last year’s record for lending in one year even before December’s figure is added. The second highest amount for one year was 9.78 trillion yuan in 2014.

Who needs QE when China’s banks are directly injecting trillions (nearly $2 trillion just in 2015) into the banking system.

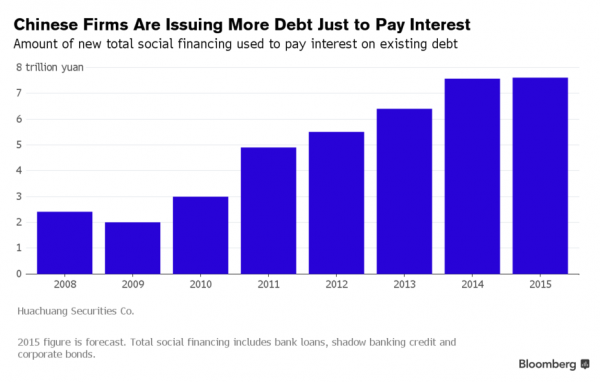

Why the need for this epic debt injection? As Caixin explains, the borrowing this year was driven by troubled companies that stayed afloat only because banks gave them new loans to pay off old debts and by home mortgages and transport infrastructure, a source close to the People’s Bank of China said.

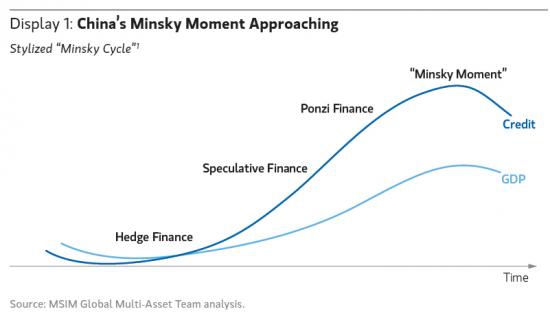

Recall the definition of the “Minsky Moment” in ponzi finance – “the moment at which a credit boom driven by speculative and Ponzi borrowers begins to unwind. It is the point at which Ponzi and speculative borrowers are no longer able to roll over their debts or borrow additional capital to make interest payments.”

As we showed a month ago, China is already at the tipping point as more and more companies have to borrow new debt just to pay interest:

According to Caixin, even in China it is becoming increasingly clear just where on the “Minsky” curve the country is to be found as several bankers said they noticed an increase in cases of companies relying on new bank loans to repay old debt. This was particularly clear in industries such as shipping, coal mining and steel manufacturing, which the government has said must be streamlined to reduce excess capacity.

One banker said these firms were often the ones known to have relied on shadowy private lending for survival in the past. As many private lending networks unraveled amid tighter regulatory scrutiny and an economic downturn, many firms are turning turned to banks for new loans to keep them afloat, he said.

“These companies are doomed,” a risk-management executive at one bank said adding that forcing banks to lend to them “amounts to dragging down the quality of the loans to non-performing.”

This is also known as the “Ponzi Finance” moment which takes place just before the “Minsky Moment” unwind, and is better known as “throwing good money after bad.”

So why do banks keep throwing good money after bad? Here is the punchline: “Banks were sometimes strong-armed by local government officials to extend loans to these companies because they feared letting them go under would cause social instability, a risk-management executive at one bank said.”

And there you have it: either keep injecting trillions in new loans, most of which will never get repaid, and whose accumulation will make the endgame that much more severe, or risk social and civil meltdown as China’s miracle 30 year credit bubble bursts.

China’s banks are pushing back, and are more inclined to make loans to home buyers than to small and medium-sized enterprises, an executive of a state-controlled bank’s branch in the southern province of Guangdong said. However, under duress from Beijing they have little choice.

The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the country’s largest bank, has changed its policy this year to permit more loans to projects such as new airports.

The bank’s former president, Yang Kaisheng, said last week at a forum that he is worried banks may be repeating a mistake of lending too much with too little information. “History has shown repeatedly that whenever banks lend too much, bad loans will inevitably increase significantly,” he said.

Unfortunately, it is far too late: banks had already lent over 1 trillion yuan more this year than in 2009, a year of heavy lending related to government efforts to soften the blow that the financial crisis has on China.

And, as explained previously, once companies begin taking on debt just to pay interest, it’s game over, and just a matter of time before pictures such as these shown here first a year ago in a post demonstrating how Chinese riot police train for a “working class insurrection“, are no longer just a drill.

Source: China’s Cost to Avoid the Dreaded Working Class Revolution: A Record CNY11.1 Trillion, and Rising