By Tyler Durden at ZeroHedge

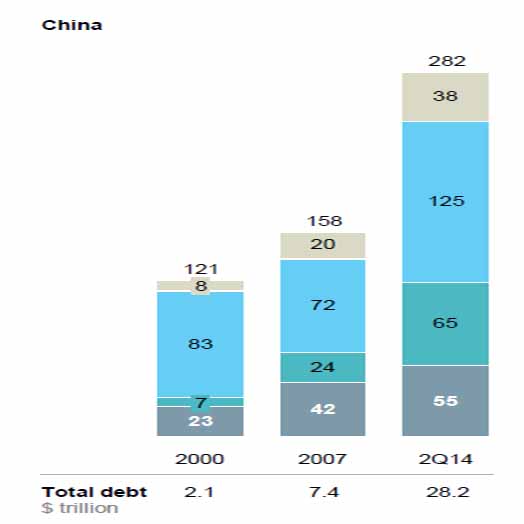

It’s almost difficult to believe, but just 8 years ago, in 2007 and right before the world was swept in the worst financial crisis in history, China had only $7.4 trillion in debt, or 158% in consolidated debt/GDP. Since then this debt has risen to over $30 trillion (specifically $28.2 trillion as of Q2, 2014) representing a staggering 300% debt/GDP.

Here is the summary breakdown from McKinsey.

This means that China was responsible for more than a third of all the $57 trillion debt created since 2007, making a mockery of the QE unleashed by all the DM central banks – something we first noted about two years before the famous McKinsey report went to print.

However, it was precisely this credit expansion that not only allowed China to completely ignore the global depression of 2008/2009 but to build lots and lots of ghost cities such as these.

To be sure, many noticed but everyone kept quiet: after all, to build these cities China not only had to create trillions in debt, it had to import a hundreds of billions worth of commodities form places such as Brazil and Australia.

Then, in the late summer and fall of 2014 something happened: for whatever reason, as we noticed one year ago, the most unregulated aspect of China’s financial system, its shadow banks, not only stopped lending money but actually went into reverse, thus putting a lid on China’s Total Social Financing expansion, which had been the world’s “under the radar” growth dynamo for so many years.

At that moment not only did China’s ghost cities officially die, but it meant an imminent collapse for China’s feeder commodity economies such as the abovementioned China and Brazil.

In the US this phenomenon was given a very simpler name by the brilliant economists: “snow.”

And since China’s domestic demand, not only from “ghost cities” but all other fixed investment was a function of pervasive credit, suddenly China’s commodity industry in general, and steel industry in particular, entered a state of shocked stasis.

To get a sense of how bad it is, look no further than China’s steel industry. It is here that, as Bloomberg reports, “demand is collapsing along with prices,” and “banks are tightening lending and losses are stacking up, the deputy head of the China Iron & Steel Association said on Wednesday.”

“Production cuts are slower than the contraction in demand, therefore oversupply is worsening,” said Zhu at a quarterly briefing in Beijing by the main producers’ group. “Although China has cut interest rates many times recently, steel mills said their funding costs have actually gone up.”

Meet the deflationary commodity cycle in all its glory:

China’s mills — which produce about half of worldwide output — are battling against oversupply and sinking prices as local consumption shrinks for the first time in a generation amid a property-led slowdown. The fallout from the steelmakers’ struggles is hurting iron ore prices and boosting trade tensions as mills seek to sell their surplus overseas. Shanghai Baosteel Group Corp. forecast last week that China’s steel production may eventually shrink 20 percent, matching the experience seen in the U.S. and elsewhere.“China’s steel demand evaporated at unprecedented speed as the nation’s economic growth slowed,” Zhu said. “As demand quickly contracted, steel mills are lowering prices in competition to get contracts.”

Actually no, it has nothing to do with China’s fabricated economic growth and it was everything to do with the unbridled credit expansion that amounted to over $3 trillion per year. That credit expansion, which has not yet been halted, is no longer making its way to the sectors in the economy, such as the abovementioned steel mills, that need it most.

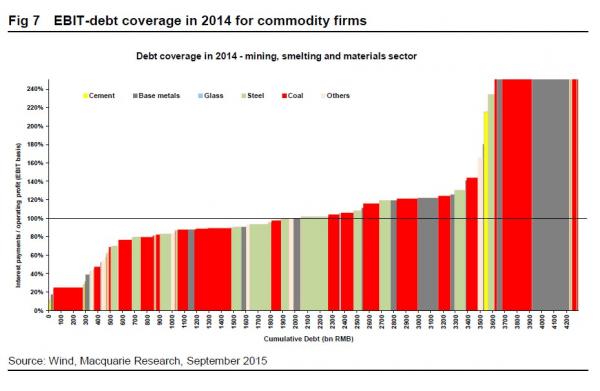

As we reported a month ago, at current commodity prices, over half the debtors in China’s commodity space are generating so little cash, they can’t even cover their interest payment. They are, therefore, utterly insolvent, and the broader Chinese bond market is well aware of this – this is the reason why suddenly credit funding has collapsed.

But wait, it gets worse: because if the PBOC had made interest rates not artificially low (yesterday China’s 10 Year bond was yielding just about 3%), eventually demand would appear, however nobody wants to lend these companies at rates approaching those suggested by the market.

“Financing remains an acute problem as banks strictly restricted lending to the steel sector,” Zhu Jimin said. “Many mills found their loans difficult to extend or were asked to pay higher interest.”

And yet in an environment of plunging interest, nobody wants to be seen as paying a huge premium above market: such an admission of defeat would be quickly perceived as a signal of an imminent default.

And this is how China’s steel (and commodity in general) sector has suddenly found itself paralyzed without access to funding, and with collapsing end demand. As a result its only option is to do more of what got it there in the first place: produce ever more in hopes of offsetting tumbling prices with surging volume, thus accelerating the deflationary spiral that much more until ultimatly steel may be literally handed away for free.

For now, however, China’s steel mills are praying this inevitably outcome can be somehow avoided.

Medium- and large-sized mills incurred losses of 28.1 billion yuan ($4.4 billion) in the first nine months of this year, according to a statement from CISA. Steel demand in China shrank 8.7 percent in September on-year, it said.Signs of corporate difficulties are mounting. Producer Angang Steel Co. warned this month it expects to swing to a loss in the third quarter on lower product prices and foreign-exchange losses. The company’s Hong Kong stock has lost more than half its value this year. Last week, Sinosteel Co., a state-owned steel trader, failed to pay interest due on bonds maturing in 2017.

Crude steel output in the country fell 2.1 percent to 608.9 million tons in the first nine months of this year, while exports jumped 27 percent to 83.1 million tons, official data show. Steel rebar futures in Shanghai sank to a record on Wednesday as local iron ore prices fell to a three-month low.

The conclusion, even though from Bloomberg, is quite terrifying: “China’s mills face some of their worst conditions ever and the vast majority are losing money, Citigroup Inc. said in September. The outlook is the worst ever amid unprecedented losses, Macquarie Group Ltd. said this month.”

China’s steel production may contract by a fifth should the country’s path follow the Europe, the U.S. and Japan, Shanghai Baosteel Group Chairman Xu Lejiang told reporters in Shanghai last week. The company is China’s second-largest mill by output.”

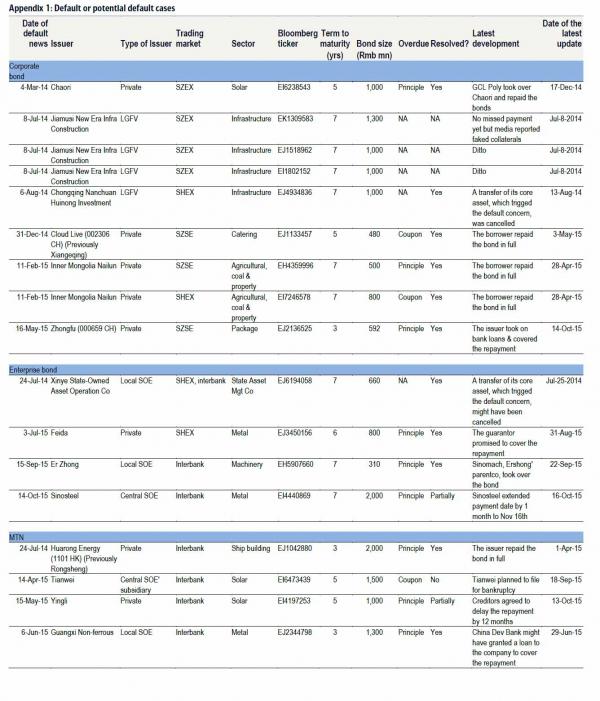

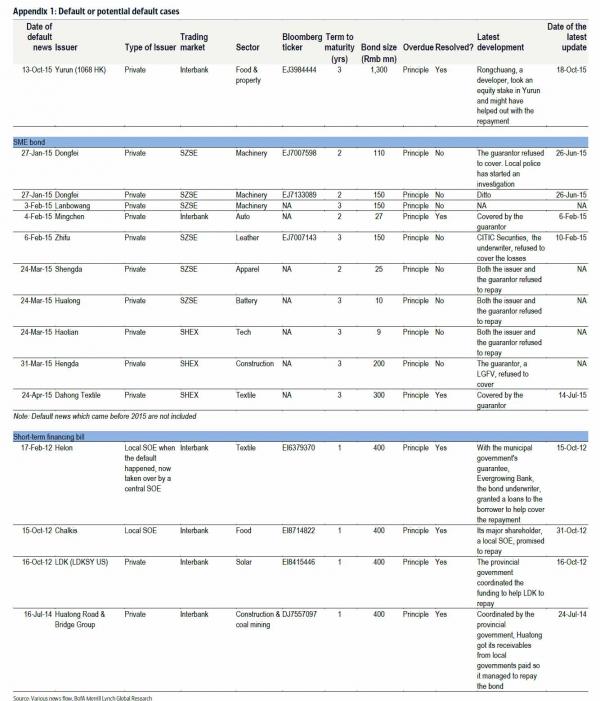

Considering China’s version of Glencore “Sinosteel” effectively went insolvent one week ago (followed by what may or may not have been a government bailout), the fallout is just starting.

The cherry on top is that China itself is now trapped: it simply can’t afford to let anyone default, as one bankruptcy would cascade across the entire bond market and wipe out countless corporations leaving millions of angry Chinese workers unemployed, and is therefore forced to keep bailing out insolvent companies over and over. By doing so, it is adding even more deflationary capacity and even more production into the market, which leads to even lower prices, and even greater bailouts!

In short: this is a deflationary toxic spiral, because while that $30 trillion in inflationary debt led to easy growth and much wealth and prosperity on the way up when prices were soaring and monetary transmission mechanisms were not clogged up, now that China has hit hit a 300% debt/GDP and the direction of the arrow is in reverse, all the growth and all the expansion of the past 7 years will be promptly unwound as mean reversion demands payment.

But perhaps most importantly, as we first reported last week citing BofA’s David Cui, we now have an ETA when this whole Chinese debt house of cards, some $30 trillion of it, bursts with consequences that will be so devastating not only China but the entire world, as the one catalyst that pulled the Developed Markets out of depression will be, poetically enough, the same one that pushed it right back in.

On the current trajectory, we doubt the market can stay stable beyond a few quarters, especially if some SOE and/or LGFV bonds indeed default.

Finally for those who would rather frontrun this runaway train when it slides off the tracks, here – again – is a list of the Chinese bonds that will almost surely default first.