By Tyler Durden at ZeroHedge

SocGen’s permarealist, Albert Edwards, has been the one person who for the past decade has firmly held the belief that a “deflationary Ice Age” is upon the world – courtesy of an unmanageable debt load – no matter what central banks do.

There is, of course, one way to short circuit said Ice Age, and it involves paradropping money in an act of terminal fiat desperation (the outcome is always hyperinflation) onto the general population, something which as we reported last Fridayis already in the works courtesy of first Adair Turner and the IMF, and soon all other “very serious people”. Keep an eye on Japan as this is where said paradropping will be attempted first as Ben Bernanke suggested back in 2003 when he said to “consider for example a tax cut for households and businesses that is explicitly coupled with incremental Bank of Japan purchases of government debt – so that the tax cut is in effect financed by money creation.”

But before we get there, here is a snapshot of where, according to Edwards, we are now and why “there” is getting very close.

In his latest note he says, quite simply, that it is now too late to put the “Orc-like monster” of excess debt and declining cash flows back in the bottle, and why “the global economy will be thrown into chaos.”

The deeply held wish of central bankers not to de-rail the fragile economic recovery is on display for all to see as they grasp at the slightest excuse for their continued inaction. The UK’s central bank governor, Mark Carney, exceeded all dovish expectations recently in his latest rate flip-floppery. But what is this? The Fed has finally summoned up its courage and looks set to raise rates next month.It is, however, already too late. Having delayed way beyond the point when it might typically have raised rates in previous cycles, it has allowed an Orc-like monster to incubate, hatch and emerge into the sunlight, snarling and ready to do battle.

Free Fed money has led to an unprecedented corporate credit binge of excess spending, especially on share buybacks. This is even bigger than it was at the time of the 2000 technology and telecom bubble. The rotten fruit of the Fed’s seemingly innocuous inaction will now be clear to onlookers as it is ripped to shreds on the battlefield by the powerful credit monster. The global economy will be thrown into chaos.

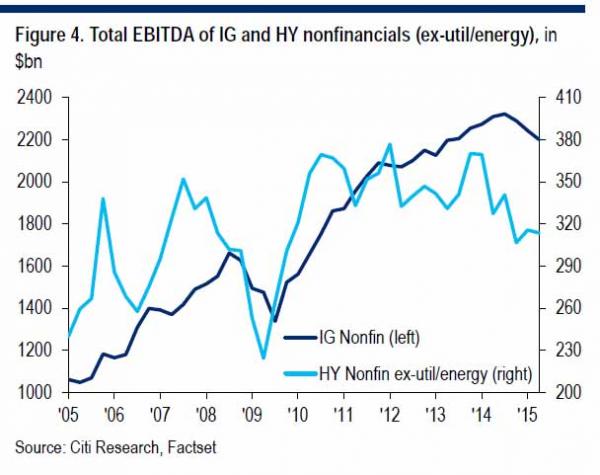

Edwards then points out something we stressed earlier this week, namely that while corporate debt has finally been appreciated, it is not the debt itself that is the risk, it is the decline in EBITDA, or cash flows.

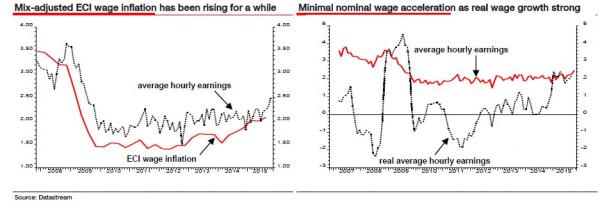

Edwards also points out something else: when it comes to real wages, the Fed is already behind the ball:

Another (obvious) reason why higher nominal wage inflation has been slow to appear, despite the tight labour market, is that it didn?t need to. Real wage inflation has been very robust indeed as headline CPI inflation has collapsed to zero in the aftermath of last June?’s oil price slump (see right-hand chart above). So wages have definitely responded as normal to the tight labour market. I was discussing this with our excellent US economist, Aneta Markowska, who is definitely more upbeat than me on the US conjuncture. But one area where we do agree is that if the oil price remains around its current level (a big if), from June 2016 onwards, headline CPI inflation will return close to the underlying core rate, which at the current rate of acceleration in rent inflation is likely to be at or just above 2%. If that is indeed the H2 2016 outturn and the labour market remains tight, we should expect a rapid acceleration in nominal wages. Although I believe things will blow up way before that, certainly by then the Fed is likely to be seen as having gotten itself way behind the tightening curve.

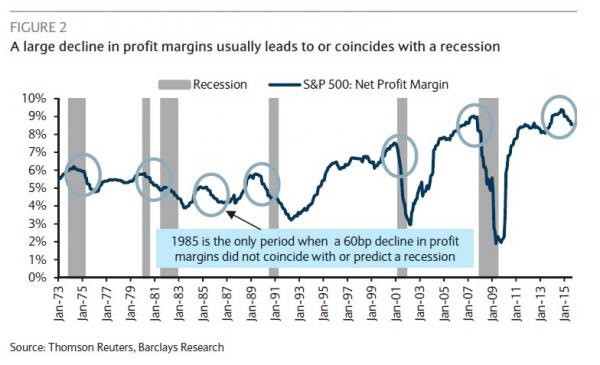

The biggest threat then is for corporate margins, which as shown below have already declined by 60 bps this cycle and fast dropping even lower:

Certainly history suggests that wage inflation cycles are a major influence in the Fed?s thinking on interest rates. But even without much of a rise in wage inflation over the past year, the deeper we go into this cycle the more unit labour costs rise because productivity growth becomes more feeble (the flip-side to the good payroll news). Indeed, productivity rose by only 0.4% yoy in Q3 2015 (versus 1.4% in Q3 last year), which when combined with a 2.4% rise in compensation (the same as last year) means that unit labour costs rose 2% yoy in Q3 this year (versus 1.1% last year). So even without rising wage inflation, profit margins are being squeezed by rising unit labour cost inflation. But what is squeezing margins even tighter is the evaporating pricing power, with corporate output price inflation slowing sharply to 0.8% yoy from 1.8% one year ago (see chart below where the red line rising decisively above the dotted line means that corporate margins are now declining sharply). With company revenues also declining this margin squeeze fatally undermines corporate profits and is central to our conviction that the US economy will be driven back into recession. And in a typical recession, where corporate profits fall sharply, what the corporate sector does not want is too much debt – oh dear, too late!

This brings us to something we pointed out a month ago: when corporate margins have dropped by 60 bps, as they have already this cycle, on 5 out of 6 prior historical occasions, this has resulted in a recession.

This time won’t be any different. Or rather, if the Fed does indeed hike just as both the global and US economy are slamming the break on growth (and going into reverse), the result could be far more dire than what was experienced in 2008.

The Orc-like monster is indeed ready to come out and play.

Source: Albert Edwards Explains Why the ‘Global Economy Will Be Thrown Into Chaos’ – ZeroHedge