Hussman has some more brilliant insights this week, which most people will ignore, because we all know he is a perma-bear who only cites facts and historical data to prove how overvalued the stock market is at this point in history. Why should we pay attention to his fact based analysis when the market is up 250 points today? But, in case someone is interested, I’ve picked out the key paragraphs from his weekly letter and I’ve bolded the sentences that make the most important points.

Hussman explains how corporations have been able to maintain record level profit margins. They’ve done it on the backs of taxpayers and the working class. The government transfers and increase in consumer debt (student loans & auto loans) have filled the gap of pitiful wage gains and kept corporate profits at record levels. Thank you Ben, Janet, Obama and a feckless Congress.

Elevated corporate profits since 2009 have largely reflected mirror image deficits in the household and government sectors, as households have taken on debt to maintain consumption despite historically low wages as a share of GDP, and government transfer payments have expanded to fill the gap, with 46 million Americans now on food stamps – a five-fold increase in expenditures since 2000. Essentially, corporations are selling the same volume of output, but paying a smaller share in wages, with deficits in the household and government sectors bridging the gap. As households and government have shoveled themselves further into the hole, corporate profits have climbed higher on the adjacent pile of earth. Deficits of one sector emerge as the surplus of another.

One problem with this scenario. Corporate profit margins always revert back to the long-term mean. The debt based profit bonanza is going into reverse. The strong dollar, increased consumer saving, less entitlement transfers (food stamps, extended unemployment) and continued pitiful real wage growth are combining to take the legs out of the ladder of corporate profits.

In short, corporate profits expand when gross domestic investment is growing strongly, the U.S. current account balance moves toward surplus (more exports, fewer imports), and the sum of household and government savings deteriorates. At present, all of these components are moving in the wrong direction from the standpoint of profit margins. Yet none of these components have moved so far that we would expect that direction to reverse. That’s another way of saying that the ladder that has supported the move to record high U.S. corporate profit margins is beginning to snap. It may be a long way down.

Corporate profits are falling while valuations are at record levels, on par with 1929, 2000, and 2007. Every reliable long-term valuation method reveals the market to be at least 100% overvalued. A Millennial entering the workforce today and investing in the company 401k will likely see the S&P 500 at the same level when they are almost 50 years old as it is today.

Though it’s not widely recognized, measures such as the ratio of market capitalization/nominal GDP and the S&P 500 price/revenue ratio are actually better correlated with actual subsequent total market returns than price/operating earnings ratios, the Fed model, and even the raw Shiller P/E (though the Shiller P/E does quite well once one adjusts for the embedded profit margin). To fully understand the present valuation extreme, recognize that the market cap/GDP ratio is currently about 1.29 versus a pre-bubble norm of just 0.55, with “secular” lows such as 1982 taking the ratio to about 0.33. To fully understand the present valuation extreme, recognize that the S&P 500 price/revenue ratio is currently about 1.80, versus a pre-bubble norm of just 0.8, with “secular” lows taking the ratio to about 0.45.

To put these figures in perspective, if we assume that nominal GDP and corporate revenues will grow perpetually at a 6% nominal rate (which is much faster than we actually observe here), and the market does not experience another secular market low until 2040 – a quarter century from now, the S&P 500 Index would still be approximately unchanged from current levels at that secular low 25 years from today.

But at least you have bonds providing negative real returns across the world. Who wouldn’t want to loan fiscally irresponsible governments run by corrupt politicians and captured central bankers trillions of dollars and you pay them for the privilege of doing so?

One obtains less extreme conclusions, though still uncomfortable, if one assumes that these multiples simply touch their pre-bubble norms a decade from now. In that case, the annual percentage change in the S&P 500 Index over the coming decade would be -2.67% and -2.26%, respectively. If all of this seems preposterous, keep in mind that these revolting long-term prospective returns in stocks are simply a less recognized variant of what we observe more clearly in the bond market, where long-term interest rates are now negative in about one third of the developed world.Investors are literally paying their governments for the privilege of lending to them on a 5-10 year horizon. Investors are collectively out of their minds if they believe that current equity prices don’t quietly reflect the same absurd state of affairs.

In addition to falling corporate profits, obscene overvaluation, and a consumer barely getting by, the economic data for the last three months has been atrocious and continues to worsen by the day. The Atlanta Fed is already showing negative real GDP for the first quarter. Increased consumer spending on Obamacare and food is not a recipe for economic success. The data below proves we are in a recession.

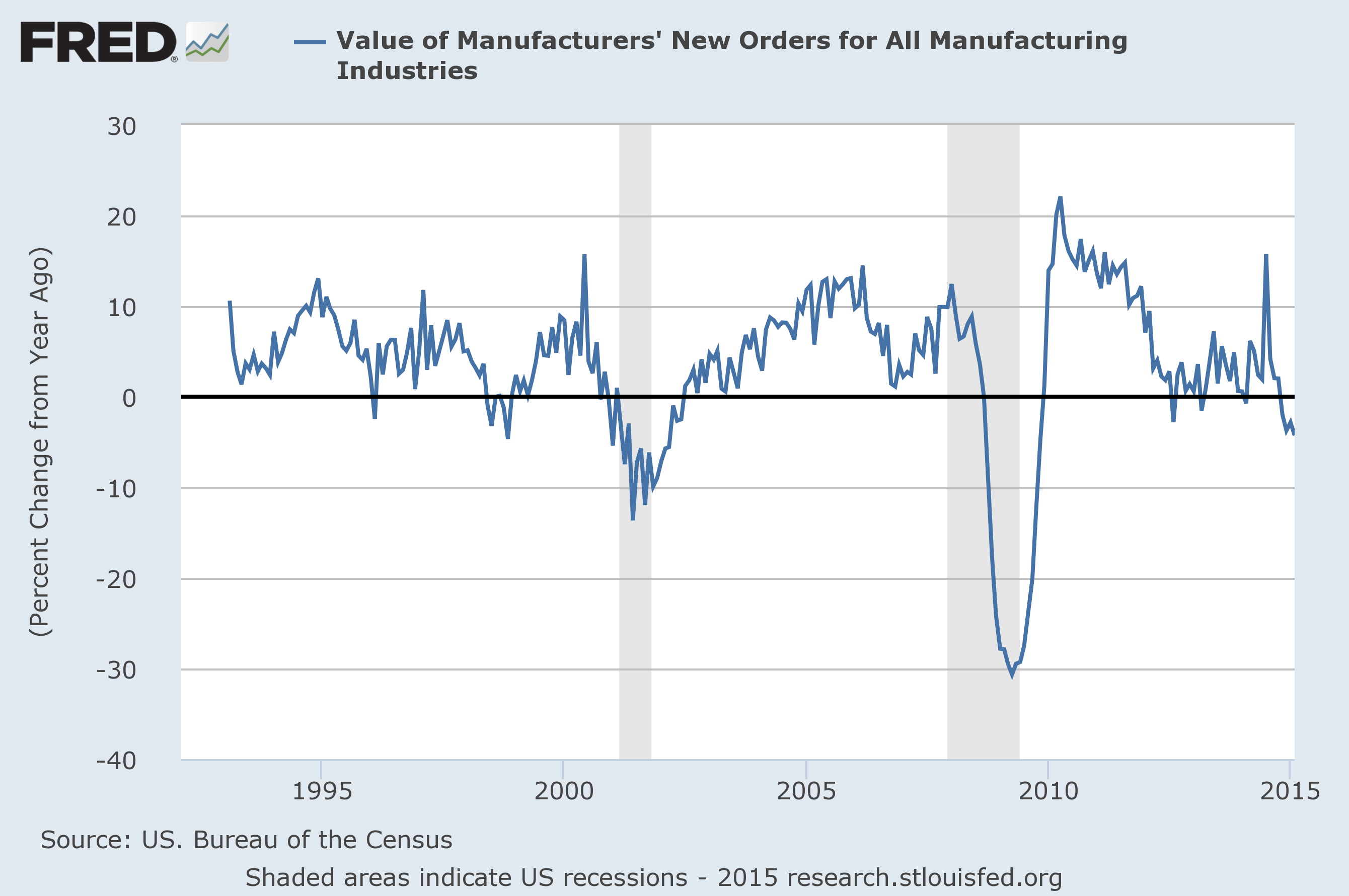

The following chart captures some of our concerns on this front. Manufacturers new orders are now contracting at the fastest rate since the past two recessions. We don’t believe there’s enough evidence to warn of a recession at present, but the data are clearly going in the wrong direction.

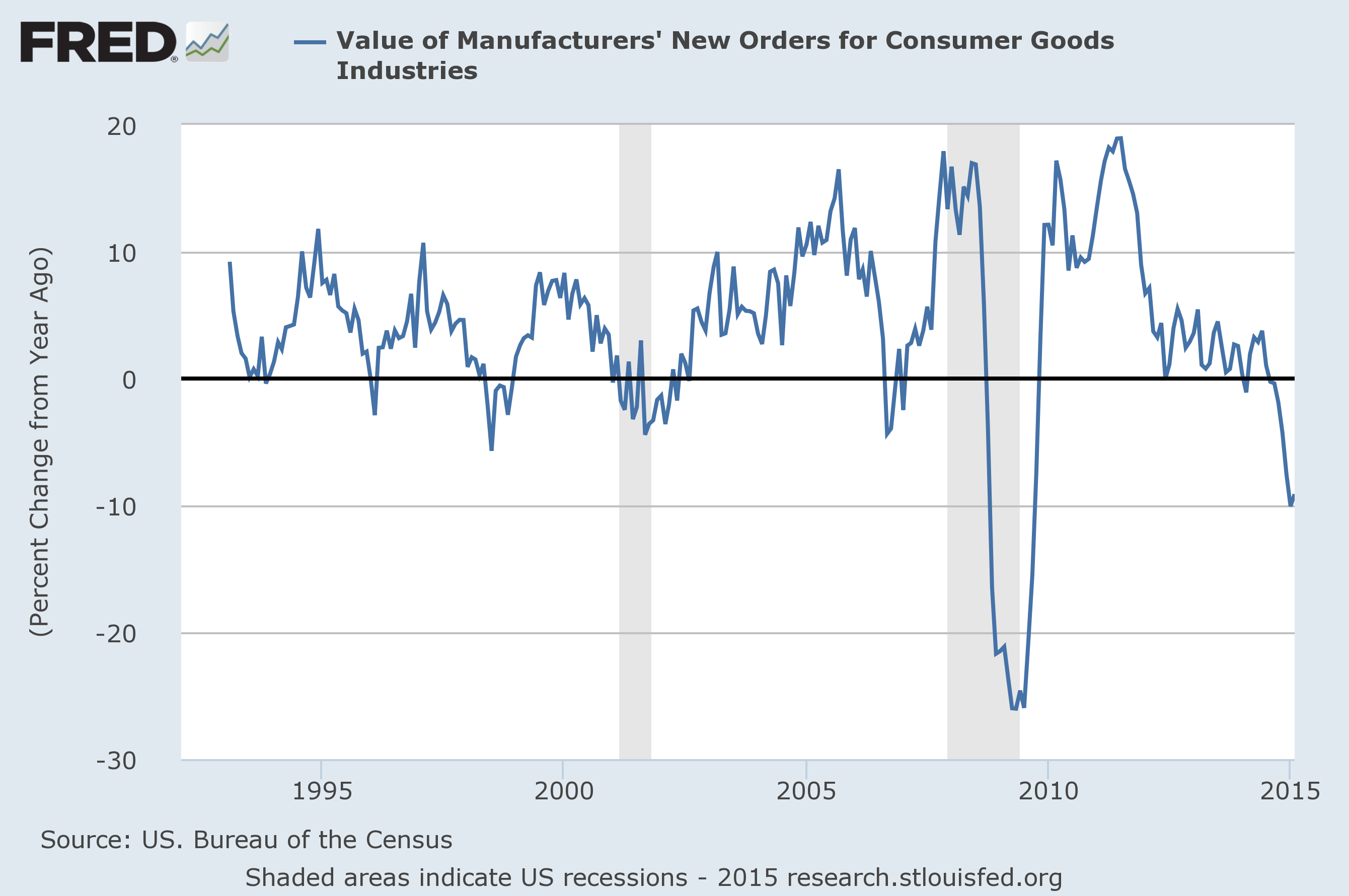

We also observe an abrupt contraction in new orders for consumer goods here, shown in the chart below.

I updated our own composite of economic conditions a few weeks ago. The chart below presents a similar index called the ADS Business Conditions Index (h/t the always resourceful Doug Short). While current levels have sometimes been observed outside of recession, our concern again is the abrupt deterioration, and the fact that the data are clearly moving the wrong way.

Today is one of the worst times in the history of the country to be invested in the stock market, bond market, or real estate market. You can ignore the facts, but that doesn’t make them not true. If you believe this is a great time to invest in stocks, you should borrow on margin and buy some Netflix. What could possibly go wrong?

Presently, we observe obscene valuations coupled with evidence of a shift toward increasing risk-aversion among investors. For that reason, I continue to believe that the present moment will likely be remembered among a small handful of the very worst points in history to invest in equities from the standpoint of prospective return and risk.

I can’t overstate that whatever a defensive investor might have “missed” in the late stages of the tech bubble, or the housing bubble, the 2000-2002 decline wiped out the entire total return of the S&P 500 – in excess of Treasury bills – all the way back to May 1996. The 2007-2009 decline wiped out the entire total return of the S&P 500 – in excess of Treasury bills – all the way back to June 1995. The intervening market gains didn’t mean a thing for investors who didn’t act at points of severe overvaluation to realize those gains. Doing so might have been frustrating over the near-term, but the completion of each cycle was ultimately very forgiving about exactly when an investor might have acted, particularly if the defensive action was at a point of market strength and overvaluation.