When the Bank of Japan announced on October 31, 2014, that it would increase the scale of QQE to ¥80 trillion annually, it noted the usual surfeit words that have clearly been passed around to everyone within network connectivity of the central axis of orthodox economics. You can honestly close your eyes and have someone read aloud the text and you would be very hard pressed, omitting specific references, to determine which central bank or nation it came from. All the buzzwords and phrases were there, including: “continued to recover moderately”, “above its potential”, “temporary weakness” that had “started to wane”, and the “decline in crude oil prices will have positive effects on economic activity.”

From all that you might ask yourself why would the BoJ need more QQE when its own argument put forth suggests exactly the opposite. Such contradictions are scarcely the exceptions, as the entire idea is itself at odds with itself. Apparently the only true economic danger in Japan, as elsewhere, is not the actual economy (which is always terrific or just about to be) but the evil, dreaded “deflationary mindsight.” So the BoJ upped its ante in case Japanese people start thinking unhappily about what QQE might not be able to do with, apparently, no real basis for them to actually think that way. Thus is the treasure of monetarism as it applies “forward guidance” and the Krugman version of “credibly promise to be irresponsible” as if nobody should notice anything but the intended happy ending. It really is the monetary equivalent of “the beatings will continue until morale improves.”

But Japanese observers, if not the Japanese themselves (who have shown a great deal of apathetic complacency even recently in sort of supporting Abe), have already noticed the broken record. It even goes back to the original QE in March 2001 when the BoJ explicitly gave much the same goals for that world’s first monetary outbreak. Reaching for something they termed the “time-axis” effect, the BoJ fully expected that reducing the rates on longer-term instruments would have a direct and opposite effect on inflationary expectations; so long as that action would continue until rates, of their own, began to rise and signal an end to the “deflationary mindset” (Krugman’s credible irresponsibility). Little attention was paid to side effects, theoretical and otherwise, including a big one right from the outset – if QE worked, or even was taken to have that potential, then bond investors would already anticipate higher interest rates from the start and therefore undermine QE before any “mindset” was incapacitated by the flooding.

But Japanese observers, if not the Japanese themselves (who have shown a great deal of apathetic complacency even recently in sort of supporting Abe), have already noticed the broken record. It even goes back to the original QE in March 2001 when the BoJ explicitly gave much the same goals for that world’s first monetary outbreak. Reaching for something they termed the “time-axis” effect, the BoJ fully expected that reducing the rates on longer-term instruments would have a direct and opposite effect on inflationary expectations; so long as that action would continue until rates, of their own, began to rise and signal an end to the “deflationary mindset” (Krugman’s credible irresponsibility). Little attention was paid to side effects, theoretical and otherwise, including a big one right from the outset – if QE worked, or even was taken to have that potential, then bond investors would already anticipate higher interest rates from the start and therefore undermine QE before any “mindset” was incapacitated by the flooding.

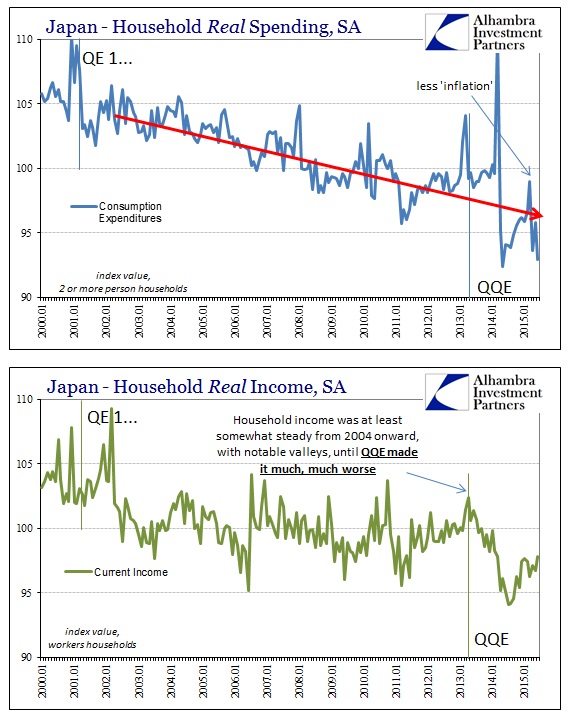

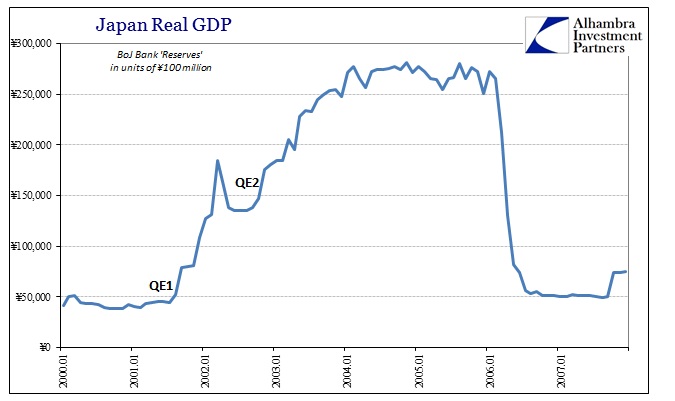

There was also the small matter of bank reserves having little actual meaning apart from signaling only what the BoJ was operationally doing. There is quite a ways between bank reserves and actual and intended action in the “market” as the wholesale morass can make plain on any occasion. Indeed, while the BoJ in ending QE in 2006 believed it had worked there is a decidedly mixed academic verdict; which is really quite damning since these are the very people who believe in it in the first place and in many cases went looking for that view. Even those “studies” that found some regressive correlations limit their conclusions to “market” or price effects rather than actively trying to overcome the burden of this:

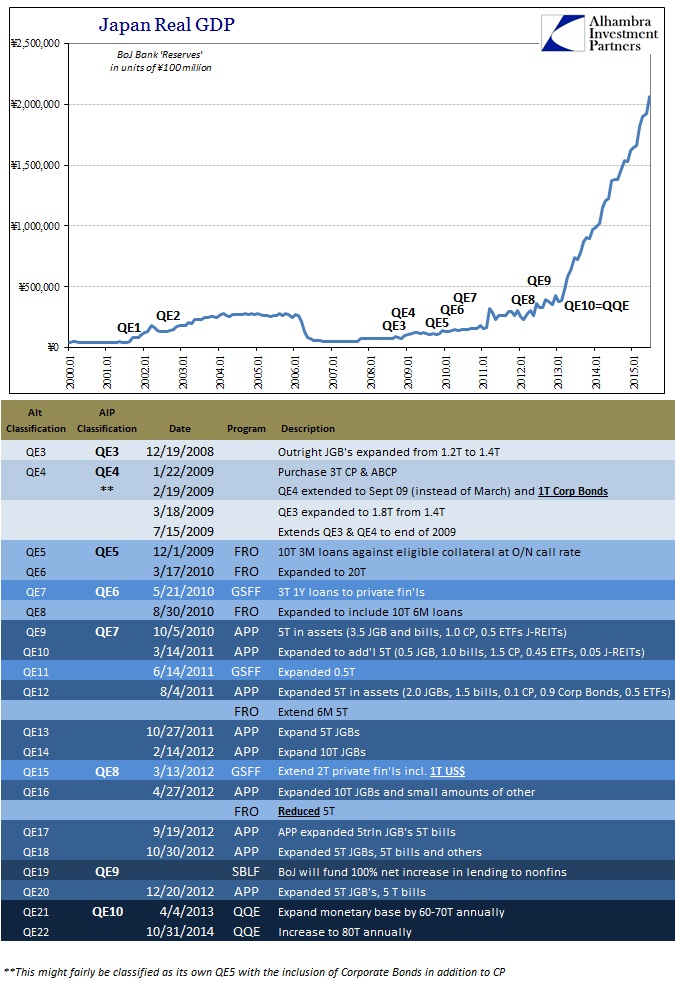

There may or may not have been some financial effects attributed to three years of increasing bank “reserves” in that first QE age (from 2001 to 2006) but there aren’t any directly detectible economic outcomes and certainly none that would suggest the primary economic goals were even close to being met. And that view obscures the fact that the BoJ in October 2002 had done just the same as it was doing in October 2014 – adding an additional QE layer. The buildup in the QE buying program was actually two, just like the Fed’s QE2 closely followed the end of its QE1. In fact, that is the universal element attached to each and every version, in that none of them (we will see if the ECB is the exception, though signs already point to not) seem to be able to achieve without subjecting at least another (and another, and so on).

In the case of Japan, it has been nine others and counting – perhaps ten depending on how you interpret and classify what the BoJ did in February 2009.

In fact, like all the rest, there is scarcely a block of the calendar since the “impossible” global panic in 2008 that hasn’t seen any of them doing something to expand their balance sheet or impress the “time-axis.” By my more conservative count, qualified as the BoJ doing something different rather than purely expanding or extending something already in progress, there have been 10 QE’s in Japan but using the numerical standard which has been applied to the Federal Reserve there may have been as many as 22 or more.

What none of those have amounted to is an actual and sustainable economic advance; NONE, no matter how you count them. In very simple fact, the idea that central banks “need” to keep doing them in continuous fashion is quite convincing that at the very least they don’t mean what central bankers think they mean, and perhaps worse that the more they are done and to greater extents the more harm that eventually befalls. It isn’t difficult to suggest and even directly observe that Japan’s economy has shrunk during the QE age, but that fact isn’t applicable to Japan alone (there are sure too many non-adjusted data points that uncomfortably assert the same for even the US). That would seem to at least offer a basis for a “deflationary mindset” no matter the actual economic effects.

So you truly have to wonder these kinds of days, like today:

Global equity markets rose on Wednesday, led by an 8 percent surge in Japanese stocks, helping lift the dollar as the prospect of more economic stimulus out of Asia soothed investors rattled by recent market turmoil.

The charge into stocks pushed yields on low-risk government bonds higher, and a sale of German 10-year debt attracted bids worth less than the amount on offer. The U.S. Treasury is scheduled to auction $21 billion of 10-year paper later.

This is not so much investing or even finance as it is a cult (calling it a religion or even ideology is unjustifiably too charitable). That is the usefulness of “deflationary mindset” not so much as a matter of actual economic pathology but as a built-in, squishy appeal to “we’ll get it right next time.” And there is always, always a next time which doesn’t seem to count for much inside the cult when, in fact, it is everything.

At least Reuters’ description of this morning wasn’t without unintentional comedy, as the article followed the quoted passage above by describing oil prices giving up “early gains, beset by ongoing concerns about oversupply.” It couldn’t be global “demand” because of all the repeated and enlarging stimulus. If energy “oversupply” could ever really be responsible for the “deflationary mindset” then the world is truly in trouble, perhaps to the point of unleashing not higher ordinal QE’s but even QE’s of QE’s. If we are going to defeat a mindset, then we must truly escape thoughts of convention and start thinking nuclear. When we get to QE^squared then we are really talking credibly irresponsible; when QE10 is remembered as a rounding error, it can’t miss, right?