The Fed’s control over money markets has always been tenuous, a myth more than anything, it just wasn’t so obvious at one time. That observation extends to its grasp of even basic operations, a spectacular fail revealed by its 2000’s treatment of the Discount Window. On January 9, 2003, the FOMC altered decades of monetary history by switching the Discount Rate. In reality, it didn’t so much shift the rate as redefine the program in yet more belated recognition that banking had drastically evolved.

The Discount Window had in the Fed’s early years been the primary monetary tool, as banks would borrow reserves directly from the one of the Federal Reserve branches. And even the 12 Fed banks would set their own Discount Rates, such was the regionally fragmented structure of national liquidity. The rise of federal funds around 1925 altered the behavior (owing in part to the Fed stumbling upon open market operations by complete accident), reducing the importance of the Discount Window in regular monetary operations. It wasn’t long before the Fed itself actively discouraged direct and chronic borrowing so that federal funds by the 1960’s was the entirety of reserve management.

That left the Discount rate as what most people think of it, the Fed as lender of last resort. The rate was traditionally set below the federal funds rate as an accommodation to those kinds of circumstances – restriction in use of the Window’s facilities was accomplished by administration rather than cost. Starting January 2003, the Fed actually replaced the Discount Window with a tiered structure called Primary and Secondary credit; the Primary rate to be set 100 bps above the federal funds target.

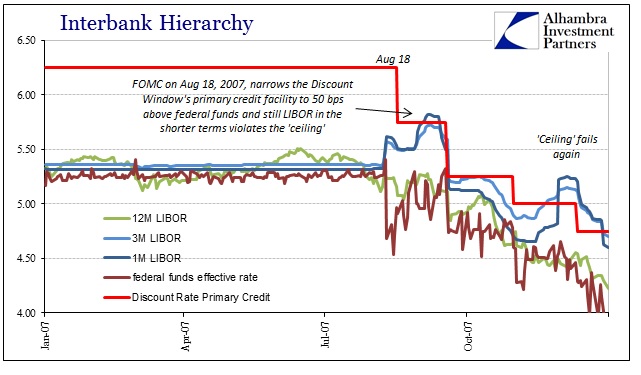

The idea was to create a monetary corridor for money market rates. The Primary Credit rate at a premium would act as a ceiling in several respects. First, the shift to something other than the Discount Window was intended to end the stigma associated with it that had been developed during the period where it was highly discouraged in favor of federal funds. The rule change to primary credit (why it is called primary credit) removed the restriction against relending any federal funds borrowed there. Prior, any bank borrowing at the traditional Discount Window was prohibited from further distributing those funds; again, last resort.

Because Primary Credit was believed to have cleansed the stigma of the Discount Rate coupled with the ability to relend, theoretically (and academically) it was expected that if money market rates rose above the Primary Credit “ceiling” other healthy banks would then borrow at the formerly Discount Window and relend those funds back into the market as an arbitrage of flow (acknowledging that the federal funds effective rate itself is not really a singular price but an attempt to aggregate and average many trades). Paired with the federal funds target (the policy rate), the new Primary Credit (and Secondary Credit) was meant to define a hard corridor for money market rates. Fragmentation was believed as a remote problem defined instead by these policy arb opportunities.

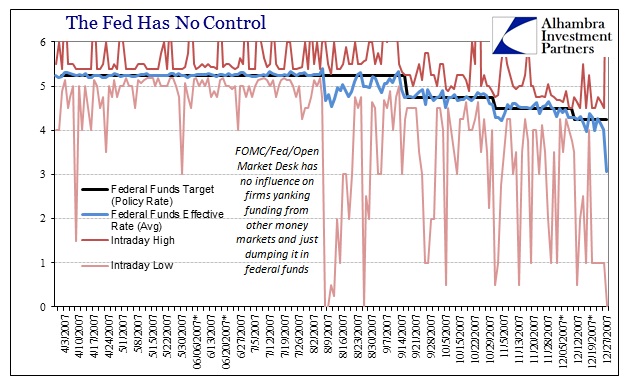

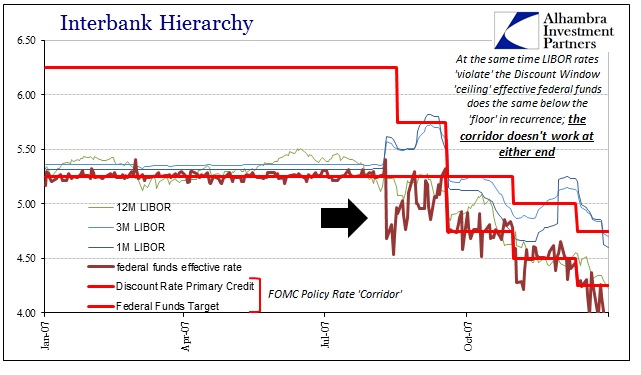

If it sounds all so bureaucratic, it was revealed and proved as such by blatant historical violations; repeated violations, no less. Starting August 9, 2007, money markets went haywire. The next day, the effective federal funds rate violated the target “floor” by an enormous and shocking amount – the target had been set at 5.25% dating back to June 2006 but the effective rate was calculated that day at just 4.68%. Worse than that, the spread was all over the place – again, the federal funds rate is not a singular rate as it is meant to represent the full “market” of actual trades taking place at different prices. On August 10, 2007, the Fed records an intraday high trade of 6.05% and a low of ZERO. The variability would continue in that fashion for some time, including frequent visits below 3% and the occasional intraday low of less than 1% and even close to 0% (the intraday low on August 29, 2007 was 1 bps in yield against 5.56% at the high!).

Contrary to convention, the first move by the FOMC in the crisis era was not the “emergency” 50 bps reduction in the federal funds target on September 18, 2007, it was actually to cut in half the money rate corridor. On August 17, only a week after the first eruption of general disorder and chaos, the FOMC reduced the Primary Credit “ceiling” by 50 bps to 5.75%, keeping the “floor” federal funds target at 5.25%. On September 3, 2007, 1-month LIBOR (eurodollars) traded above the Primary Credit rate, fixing at 5.765% and then staying above 5.8% for the next week.

In late November, it happened again even though the Fed had unleashed additional “stimulus”; both 1-M and 3-M LIBOR surged while 12-M LIBOR and the effective federal funds rate continued to shallow. Money markets were all over the place with very little attention paid to the Fed’s “imposing power” to enforce anything.

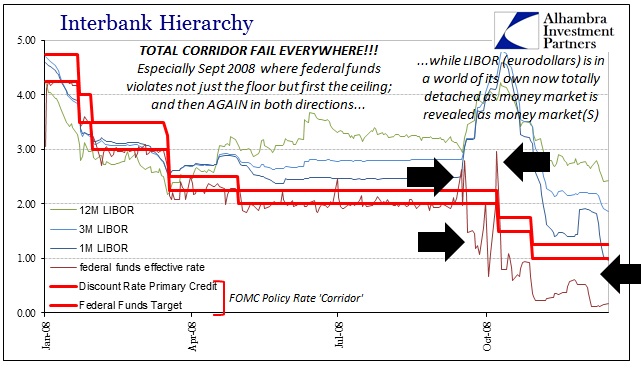

In response, the Fed narrowed the corridor yet again on March 16, just as Bear Stearns failed. At that point, and the FOMC discussions then confirm this, monetary policymakers largely believed that they had overcome the worst even though they still recognized serious downside risks. The basis for that belief? Not reality:

It is an enduring testament to ideological blindness as to why they thought they had regained control – and just about the money markets! As is plain above, eurodollars had completely broken away after Bear Stearns, as LIBOR leapt all over to a large and conspicuous premium. Meanwhile, the federal funds market hardly “behaved” as it was much more volatile and as prone to violate the Primary Credit “ceiling” as at any point in wholesale history. And then the events of September 2008 which proved, beyond any doubt, that the Federal Reserve is entirely helpless in its framework when pressed.

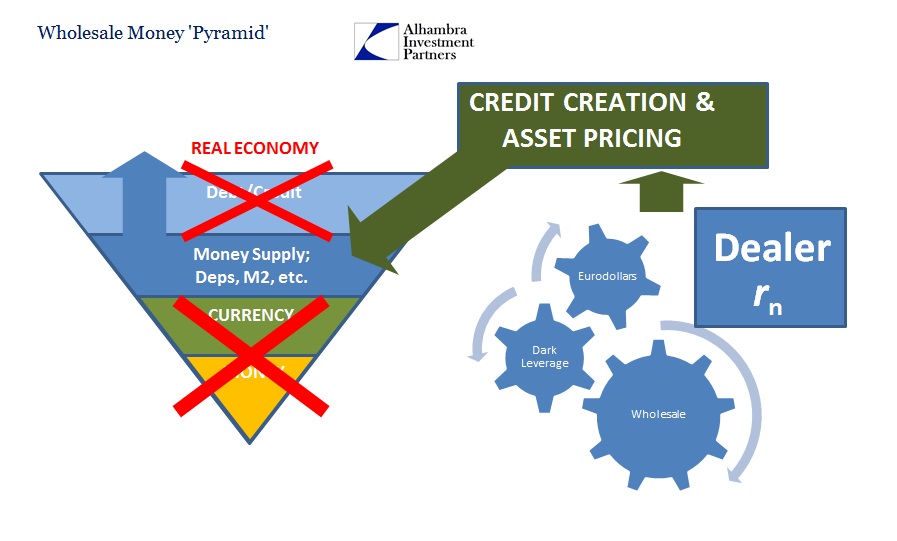

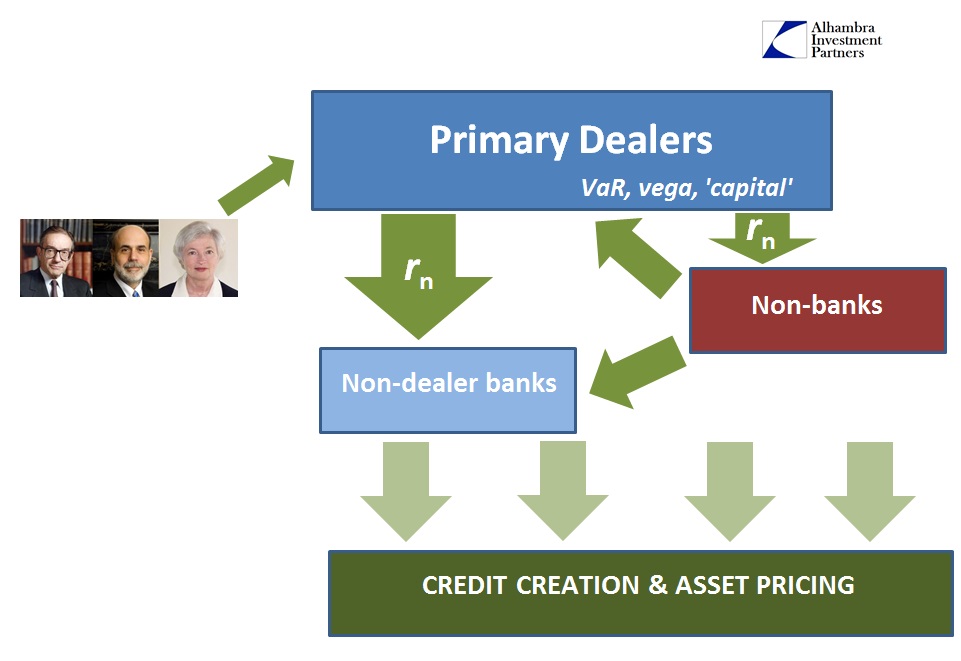

And that is the relevant point to our conditions right now. The money markets seem to follow policy decision only under benign conditions. Past some unknowable threshold, money markets become money market(S) with the Fed strictly powerless to enforce any kind of order and restorative measures to bring them all back into singular and seamless function. That makes its primary job of lender of last resort fully indefensible and untenable, which explains a great deal as to why we are where we are. In other words, the money market fragmenting as they did starting in August 2007 owed to the idea of intermediation, or specifically where there were no money dealers to perform it.

However, as the history of these markets amply demonstrates, they require action, activity and resources of intermediation to become apparently so. The very word that should most be applied to banking, but no longer is, is “intermediation” – literally meaning standing between two or more factors and bridging the gap. Money markets are not something themselves, they are the outcome of action and financial production…

Central banks simply cannot perform the “correct” intermediation in order to recreate money markets as they existed before August 2007; it is just impossible. That means either they have to find an alternate solution or get used to being the permanently lacking ad hoc workaround. Neither of those should be considered anything like “normalization” not least of which is because the Fed isn’t prepared for any of it.

Central banks are poor money dealers; unbelievably poor given that they declare it their first and foremost task (currency elasticity). What is contained above describes how disastrously the wholesale “dollar” system went from A (money dealing of eurodollar banks) to B (central banks just taking over everything, but only after it had all collapsed; and I haven’t even added repo here, which is yet another feather of central bank comedy of misunderstanding and function). There is no going back to A, as the dealers themselves have made so very plain especially since November 20, 2013.

It is, then, quite understandable that the Fed would run into resistance now given that benign is not the operative description of money markets here or globally. It may more aptly be described as the other way around, as the money markets do what they try to do with the Fed arrogantly imposing its opinions as if they were gospel. The Fed does not have control, they just claim to. Because of that, they were shocked as to how 2008 turned out. That is a state they have yet to leave behind.