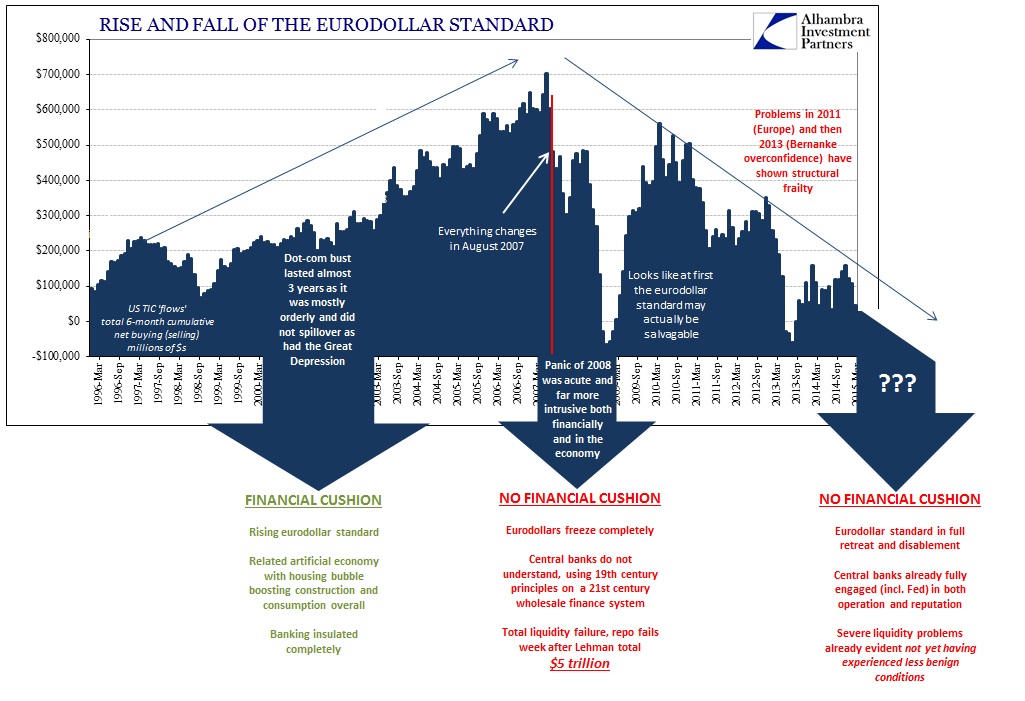

Yesterday was the eighth anniversary of the end of the eurodollar standard as a functioning system. Though the attainment of such dizzying scale was completely artificial, finance unbacked by real economy, it at least to that date had remained in more than superficial order. Reviewing the systemic break of that day remains quite useful in understanding where we are now, and thus where this might all still, almost a decade on, be heading.

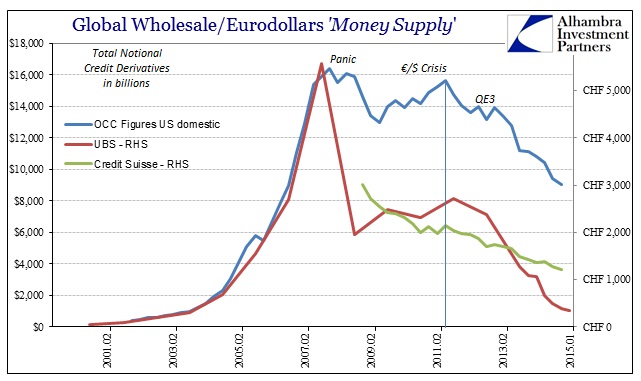

The deep rift in global finance that opened then can be seen in various ways. More recently, it has appeared as raw impotence on the part of central banks. This year has made that clear ever more so than even the past few years because central banks everywhere are no longer anywhere near their most basic, economic level – “inflation.” The link between economy and consumer price changes has always been tenuous, but it had remained a core principle not just in guiding central bank policies everywhere but also in generating the basis for conventional perceptions about monetary policy power; print a ton of money and inflation should show up.

Thus the “dollar” and commodity plunge dating back to last year creates not just doubts about monetarism and economy, but the raw component of whether central banks can do much of anything they say.

That is a huge change in perception from before August 2007. The change in views about monetary policy did not, of course, alter on that date specifically but in the most esoteric of financial, wholesale function the pathology leads there; widespread recognition would only follow so long as that remained true and it clearly has. In very general terms, central banks could do no wrong prior, and then “suddenly” have been able to do nothing right since. The Great “Moderation” was, after all, a public relations effort to codify and harden perceptions around that first part, even to the point that though the Fed, in particular, lost some luster in the dot-com affair it retained almost universal celebration for how it (supposedly) engineered out of it.

The titanic shift in August 2007 cannot be overstated. The Fed (and all its central bank network) continued to do as it had done before, starting in September 2007 with its first very orthodox, quite textbook 50 bps cut in the federal funds rate. From then on, no matter what it did, the financial system remained unaffected and so with it the economy. That has continued, after but a brief and tantalizingly hopeful interlude during the latter months of QE1, uninterrupted to today. QE’s all around the world and still “inflation” is by far (and “unexpectedly”) more zero or less than not and not a recovery in sight anywhere.

The exact details of early August 2007 matter only slightly in this rearview examination, and only as a means to highlight the jump from unspecified worry to irreparable systemic harm. There were numerous warnings in the months before August 2007, most especially the failure of two Bear Stearns funds (“high grade” though they were labeled). Rumors and whispers abounded that “contained” was ludicrous, and ABX indices were already finding irregularity (which was the full part of Bear’s problems). The turn to July 2007 brought with it more specific names, such as Countrywide.

Countrywide had been the target of much speculation but had resisted admitting anything more than what was obvious. That didn’t help, and in fact turned out to be arguable in terms of veracity in amplifying the transition. It had always assured the “market” that though the company was being roiled by “softening home prices” (as it claimed in its quarterly report of July 24) there was no liquidity problem whatsoever. That changed on August 9:

On August 9, 2007, Countrywide issued an additional press release disclosing the Company’s potential-short-term liquidity issues, directly contradicting the Company’s earlier assurances. Specifically, the Company warned of disruptions in the debt and secondary mortgage market that would likely affect the Company’s short-term financial condition and earnings. Upon this disclosure, the Series A Debentures fell another $1.37 per debenture, or 1.48%, to close at $91.00 per debenture on August 10, 2007. The Series A Debentures continued to decline steadily to close at $84.81 per debenture on August 15, 2007, just one week after the August 9, 2007 disclosure, representing a total drop that week of $7.56 per debenture, or 8.18%. The Series B Debentures fell another $0.98 per debenture, or 1.08%, to close at $90.02 per debenture on August 10, 2007. The Series B Debentures continued to decline steadily to close at $81.94 per debenture on August 16, 2007, just one week after the August 9, 2007 disclosure, representing a total drop that week of $9.06 per debenture, or 9.96%.

It wasn’t just Countrywide but a whole host of other “irregularities” that suddenly appeared. “Liquidity” as a concept had been, even for “seasoned” market observers, more fuzzy but here was its primary downplay being acted out in wide scale fashion – liquidity was actually acting out a systemic pricing problem, the first in the general and worldwide cascade.

`The complete evaporation of liquidity in certain market segments of the U.S. securitization market has made it impossible to value certain assets fairly regardless of their quality or credit rating,” BNP Paribas said in a statement.

That was a declaration BNP issued on August 9, 2007, halting withdrawals from three investment funds. Note both the relatively limited exposure of those funds (subprime) as well as the “ratings” (while not forgetting this was a European conduit):

The funds had about 1.6 billion euros ($2.2 billion) of assets on Aug. 7, after declining 20 percent in less than two weeks, spokesman Jonathan Mullen said today. The bank will stop calculating a net asset value for the funds, which have about a third of their money in subprime securities rated AA or higher.

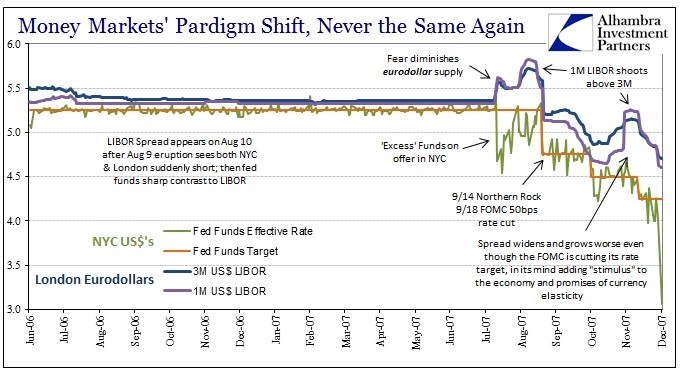

To that point, all this seemed limited to bond prices and not general recoil across “money markets.” One-month LIBOR had been 5.32% for 106 consecutive days dating back to March 2007, increasing a few pips on August 1; three-month LIBOR had been 5.36% of within a few pips of that for 63 consecutive days – all the while “deeper” financial indications and prices were already going haywire. Thus, it was to that point at least plausible that this all could be “contained.”

The shift started on August 8, as both one-month and three-month LIBOR jumped by 2 bps. It doesn’t sound like much, but it was. The next day, the first of the unalleviated downside, three-month LIBOR surged 12 bps while one-month LIBOR spiked 19 and an eighth. It hasn’t been the same, quite literally in money markets, since, so obvious that only the most committed of orthodox ideologues could miss it:

I wrote on the occasion of this anniversary last year a fuller explanation of the “money” side, but the general terms still easily apply:

Why bring all this up, particularly after seven full years now? The first reason is simple, since from then on we have seen an absolute intrusion into market function of historic proportions and all in the name of “stimulus.” To what gain? We got the Great Recession anyway in spite of it all; and nothing like a recovery afterward. The very reasons for total market repression were born that day in August 2007, to be repeated at every questionable instance (like September 2008 when there was no real panic outside of banks).

Second, and perhaps more important with regard to the future, the FOMC demonstrated both a blindspot and a curious ignorance about the systemic weaknesses of “its” financial system. The crisis period shows not just one limited instance of the feebleness of monetary response, but rather the template by which monetarists will fail time and again. When you are captured by systemic ideology, you will never see the cracks in that system from looking inside out.

We are told that the liquidity system has been repaired in the years since, but we know that to be false, not just in the failure to create a durable interbank rate floor, but by the persistent and regular repo market fragility. It is a signal of systemic bottlenecks or weakness that is the very same manner by which the paradigm began to shift the first time.

It was perhaps more arguable last year at least in the sense that continued financial disruption was, like that before August 9, 2007, limited only to those specific circumstances; in 2015, that is no longer the general assumption even if orthodox economists hold out on the still-awaited recovery. The lack of recovery, the feeble and continued responses of central banks the world over, all of it derives from that systemic interruption eight years ago.

The panic in 2008 was a tremendous opportunity to break from the artificial chains of eurodollar socialism (which is what all that really was; breaking the economy down to discrete cases, arranged by redistribution toward finance-first, so that it could all be socialized and thus “managed” from the top-down). In other words, the end of the “dollar” isn’t something to be feared, but only in the case where the end of the “dollar” is once again “accidental.” Every effort, including and very especially TBTF, was made to try to rebuild the system as it was in total ignorance that that was no longer even a possibility. Everything since then has flowed from that one fact.

Had orthodox economics awoken itself to the very evident reality of systemic function, the end of the “dollar” could have been, long before now, celebrated as the liberated global economy, no longer dominated by eurodollar and wholesale financialism, found its own, natural and very likely robust and stable recovery. Instead, we are stuck in another of the serial asset bubbles looking quite seriously at another go around while the FOMC, ECB, and all the rest puzzle about “secular stagnation” as if it weren’t all in them this entire time.