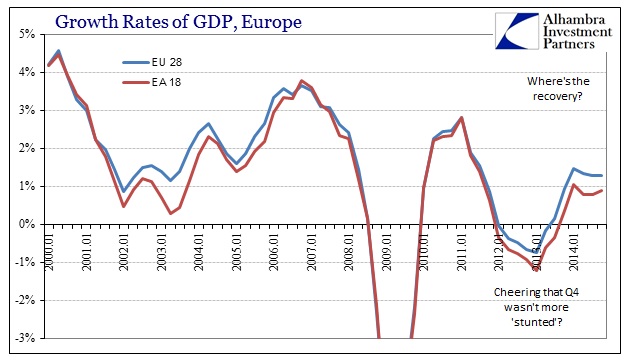

There has been a lot made of the fact that European GDP wasn’t worse in Q4, especially as Germany rallied to the continent’s economic defense. While initially the reactions were unabashedly positive, I think reality set in more so later after fuller digestion. In other words, everything we thought about Europe before today is still a problem, only that Germany pulled forward or “borrowed” some “demand” from Q1.

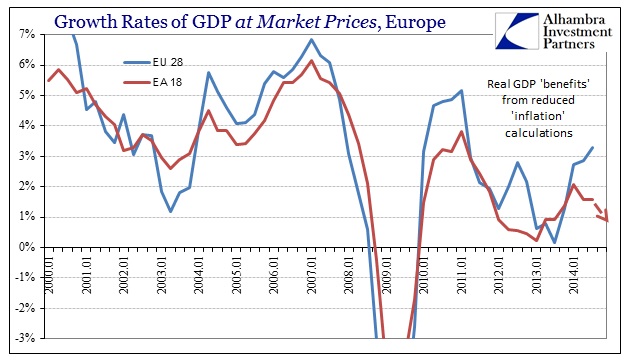

In any case, though Eurostat hasn’t updated its full database yet (this was the “flash” GDP reading, after all), Q4 was undoubtedly “aided” by Europe’s descent into “deflation.” The only question remains to what degree has nominal GDP degraded over previous quarters. Like Japan’s three decade journey, there is nothing about a negative calculated inflation rate that “helps” an economy – only the simple math of how GDP is constructed.

So even in real terms there is nothing to be excited about, only that the stunted nature of 2013’s “recovery” from the prior “recovery” isn’t yet worse. Until we get the fuller updates from Eurostat, we again don’t yet know what GDP looked like in nominal terms, but given the HICP inflation figures for the last three months of 2014 we have a good idea.

I would not at all be surprised if the GDP deflator in Q4 was near or even at 0.0%. The average of October, November and December HICP was just 0.2%, which means nominal GDP fell from 1.6% Y/Y in Q3 to probably less than 1%.

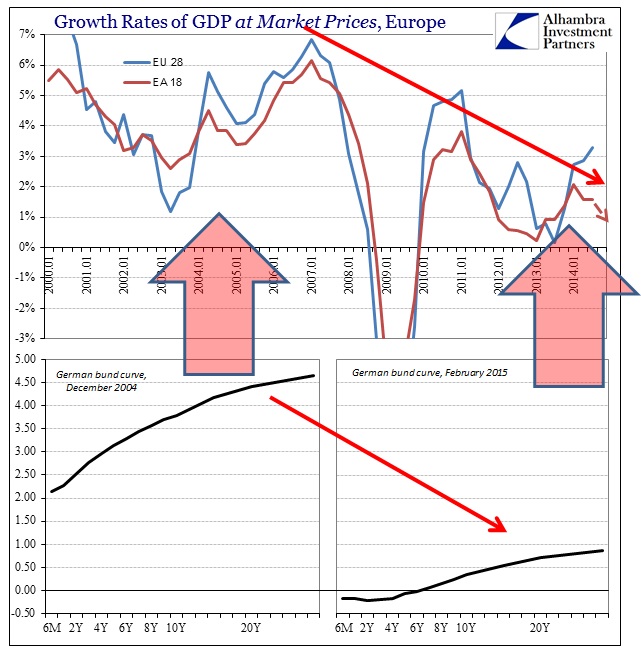

So it is odd to hear economic commentary excited by the decay in nominal GDP especially since orthodox economics spends so much time there. The entire point of monetarism at the zero lower bound (and below it, as in the case of the ECB) is to ensure that inflation expectations, and thus inflation itself, is rising. In GDP terms, everything the ECB has done since the LTRO’s is to get credit flowing and nominal GDP moving upward if not rapidly then at least consistently. As you can see above, it is doing neither, having sunken in 2012 well below the 2001-02 recessionary period and remained there.

The cratered view of nominal GDP comes exactly during the period where the ECB has been the most active, including Draghi’s promise. So everything the central bank has done has been with that view in mind, one that also proves total failure on their part. If trillions of euros in “liquidity” has so little effect on even nominal GDP (which is constructed to be the most favorable view of an economic system, especially now it has been “updated” to include new methodology) then what are economists basing future expectations on? Take out Germany and everything above is far, far worse.

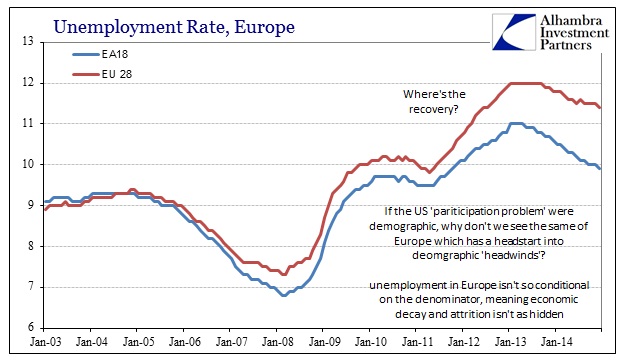

The ultimate point of any economic system is not activity for the sake of activity but rather to foster labor specialization in a broad-based and sustainable expansion – that is, wealth over mere transactions. Like the US, Europe (even including Germany) isn’t seeing any wage growth, but unlike American statistics Europe is not hiding its labor problems in the denominator of the unemployment rate.

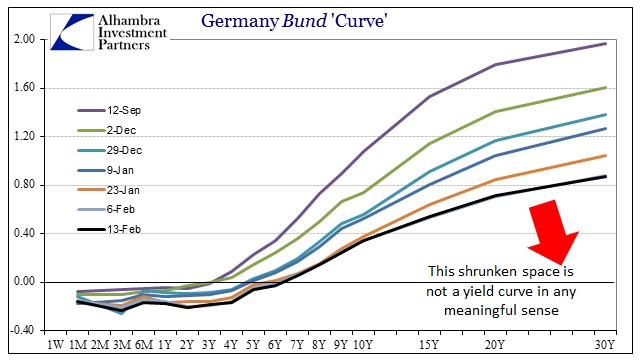

As for reaction, credit markets in Europe were decidedly unimpressed by the numbers. The German bund curve remains mired in its shriveled existence.

Though you can’t see it directly above, the curve this week is almost identical to the curve last week – meaning that German credit is unmoved by all the sudden sparks of “deflation helps GDP.” In fact, given how so many other parts of the credit markets have been in a relief “rally” (selling bonds) it is actually somewhat pessimistic to see German credit, where GDP was supposed to be the best, remain unmoved.

Like so many other things, this all really amounts to just splitting hairs about how bad things really are. The GDP and unemployment charts above show it quite well, as there has been no recovery in Europe in pretty much anything since 2009. The shriveled bond curve is a perfect encapsulation of the age, as the more “money” dies the worse the economy becomes – to the point now where debate centers on whether GDP is just stuck at a recessionary level or sinking once more. That, too, is a reflection of the current debilitated state, where even standards of measurement are as shrunken as these yield curves.

There can be no denying the correlation; the more basic finance is repressed by monetarism the less the economy does even in nominal terms of GDP. You might make a “chicken and egg” argument about whether the economy is to blame and the repression is in response, but the correlation is obvious. In light of how little the European economy has responded to repeated and intensive monetary outbursts, my “money” is on the causative side residing with and around repression. That view and interpretation actually includes the Great Recession, global as it was, since proper analysis actually interprets and incorporates far more than just the most recent periods.