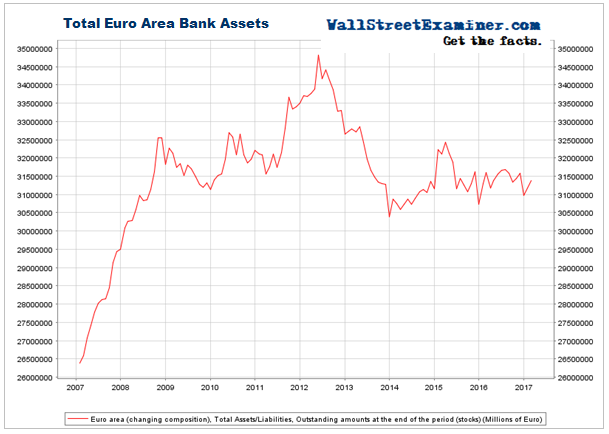

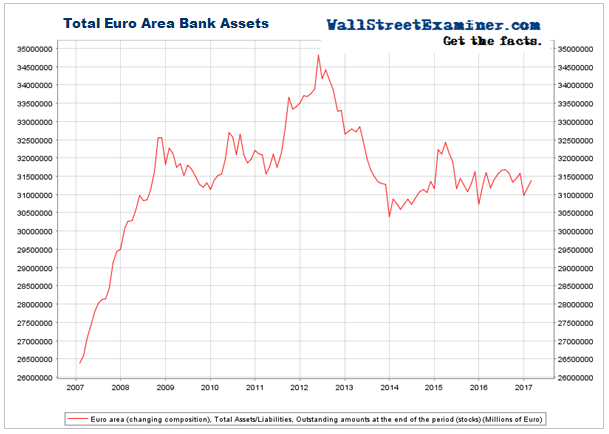

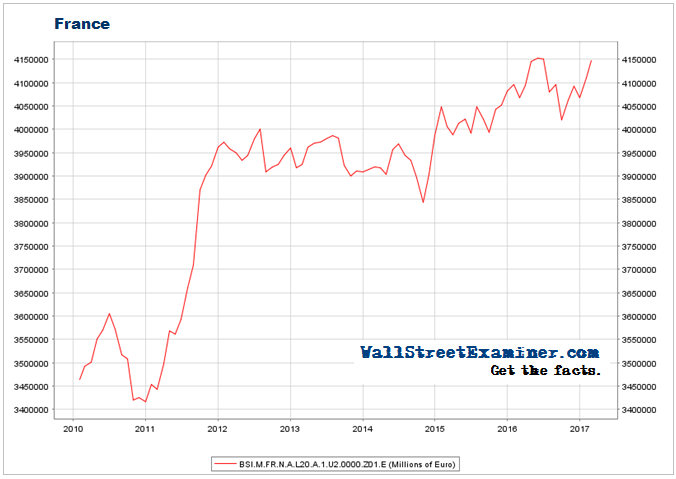

Total assets in European banks rose by 0.7% in February after a 0.6% gain in January. However, those assets are still down by over 10% since mid 2012. They remain within the same range they have been in since December 2014.

Bank loans haven’t grown at all since NIRP (Negative Interest Rate Policy) and QE were instituted. Loan growth has been stagnant even though the ECB was adding €1.9 trillion in assets to its balance sheet, which began in September 2014.

The ECB continues to buy €65-70 billion in bonds from the European banking system. Over the past month it bought €69 billion.

It also just added a couple of hundred billion last week in the form of new TLTRO loans. We don’t know the exact amount yet because it came after the weekly statement closing date. Some older LTRO may have been paid off.

The LTROs are 4 year loans to the banks for the purpose of stimulating new lending. The banks get paid an interest bonus by the ECB if they increase their lending. If they don’t, then they must pay interest on the money (a very low rate, of course). Since loan demand is virtually dead, the banks must have had something else in mind when they took down so much of the TLTRO. Maybe it was an attempt to shore up their own cash as the banking crisis in Europe deepens.

QE and NIRP have been a gross, unmitigated failure at achieving what they purportedly were supposed to do. The ECB’s solution? Do more of it.

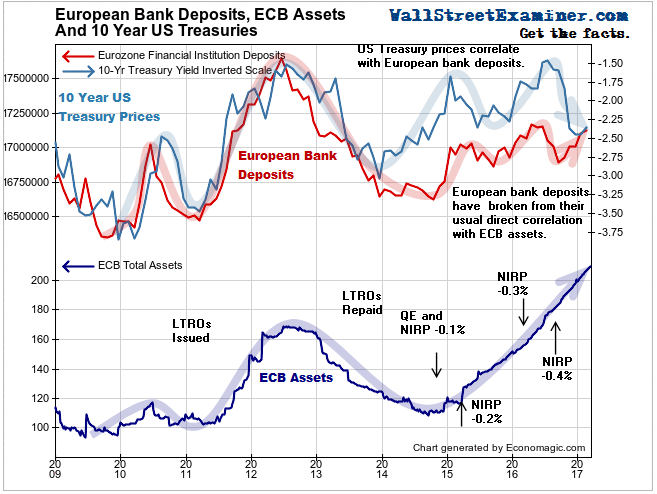

Total Deposits

Total deposits in European banks rose by a whopping 0.1% in February. That comes on the heels of a slightly more impressive 0.6% gain in January. These gains continued a rebound from the September 2016 low.

Why are more Europeans keeping their money at home? Could it be…? Satan? Or Trump? The rebound really picked up steam after the election and then again last month, which coincided with the inauguration.

I’m just speculating of course. But I have seen the negativity toward Trump in Europe first hand. I would not doubt that many Europeans are pulling money out of US securities investments, particularly Treasuries.

Deposits have declined by €47 billion since they peaked in April 2016. Considering that the ECB added €888 billion to the banking system over that time, that means that €935 has either been extinguished or has been transferred out of the European banking system, probably mostly to the US.

I wrote in the beginning of March that, “I would speculate that a breakout in European deposits above the April 2006 peak would be a bearish sign for the US. Cash inflows from Europe have powered much of the US rally. If European investors and businesses decide that it’s less risky to keep their cash at home, then European demand for US stocks and bonds will diminish. It hasn’t shown up in the lagging European bank data yet, but it’s something to watch for.”

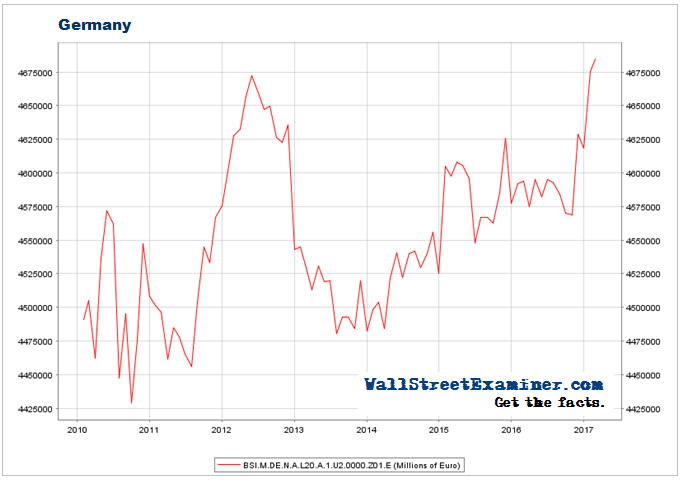

National Banking Systems in Europe – Some Still Grow, Others Contract

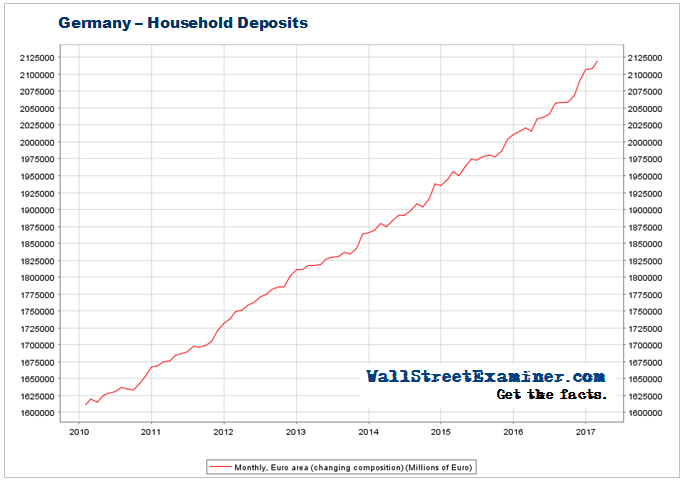

Deposits in Germany rose in February after surging to a new high in January. This is the big driver of the increase in total deposits in Europe. But it is a pattern we have seen before from the German banks. Spikes are usually largely reversed within a few months. Also, the chart scale makes this rebound look bigger than it is. The annual growth rate is now still just 2% after this “massive rebound.”

Again I would speculate that if this continues, Germans are pulling cash out of the US, largely by selling their US investments.

After the completion of the LTRO paydowns in 2013, German bank deposits bottomed at €4.48 trillion euros. They’re now at €4.68 trillion, a gain of 3.5% in 3 1/2 years or about 1% per year.

That compares with the growth of US deposits slowing from around 10% in late 2012 to 3.5% at its lowest point in 2016. Currently the growth rate of US bank deposits is now around 5.4%. If US deposit growth slows as German deposits rise, I would take that as a bearish indication for the US.

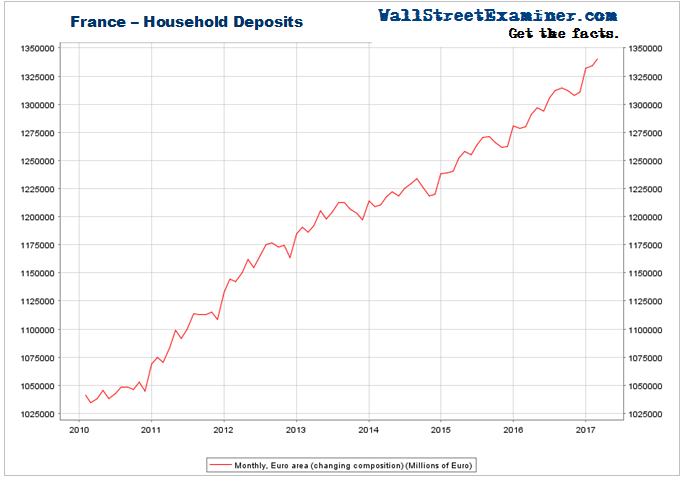

French bank deposits rose in February, but are lagging Germany’s recent growth spurt. Total deposits have yet to clear last years peak. The stop start path of deposits in both countries is a sign of central bank interventions, not intrinsic economic growth.

Unlike total bank deposits, household deposits have gone only one direction–up.

While total deposits have had hardly any growth, German (and other European) households continue pouring money into German bank accounts. Why they are doing that is a mystery, but the simplest explanation is that they have no reasonable alternatives, especially for depositors in basket case countries like Portugal, Spain, and Greece.

But also, in recent months I suspect that there has been a wave of repatriation out of the US. European news media portray Trump as the jackass that he is. That’s not good for foreign investor confidence in the US.

We see the same dynamic in France. Household deposits in French banks surged to another new high in February, rising by 4.7%. Here again, households have fewer options than big business and institutions about where to keep their cash. By the same token, total deposits in French banks only grew 2%. That means that like in Germany, commercial and financial depositors are fleeing their banks.

I will continue with other countries that are basket cases, the flight of banks from one another and loan data that shows no growth in a forthcoming post.