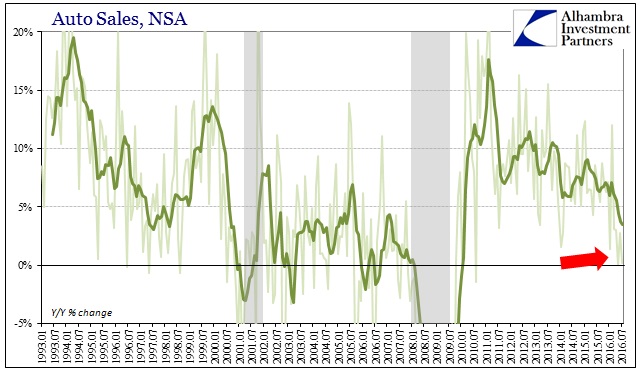

If the labor market were slowing as the wider perspective of the payroll reports suggest, then it would make sense to find increasing difficulties even among the few bright spots in this otherwise anemic economy. Yesterday and earlier it was reported increasing signs of slowing in real estate, both construction and resales of homes (particularly dwindling inventory). In the past few months, that possible consumer strain was also observed in auto sales, the one part of the manufacturing economy that had appeared immune from depressionary forces plaguing much of the rest.

The word “plateau” has been used recently in describing predictions for consumer spending on autos the rest of this year, given to us by Ford officials who remain in their position that sideways is the worst we can expect – at least for now. August auto sales further raise the possible that the plateau may instead be the best case.

U.S. auto sales fell 4.2 percent in August as some major automakers said a long-expected decline due to softer consumer demand had begun, possibly sparking a shift to juicer customer incentives and slower production.

Still, Ford’s management manages to use that word:

“We think sales have reached a plateau, and at that plateau we’ll see some month-to-month volatility,” Ford senior economist Bryan Bezold said.

Ford sales fell nearly 9% in August, which isn’t so much of a “plateau” after falling “just” 3% in July. Overall sales at other carmakers were not as dismal but concerning nonetheless: GM -5.2%; Toyota -5.0%; BMW -7.2%; Honda -3.8%; Nissan -6.5%. The only major manufacturer to manage a gain was Fiat Chrysler, +3.1%.

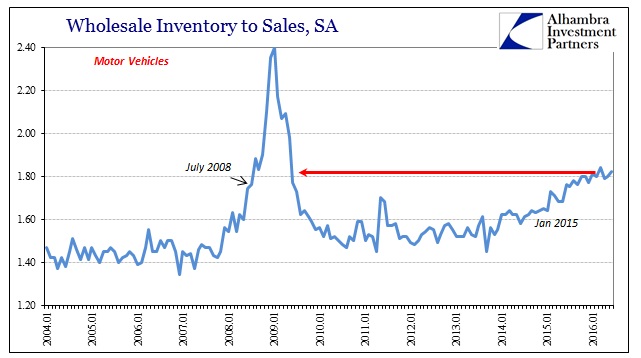

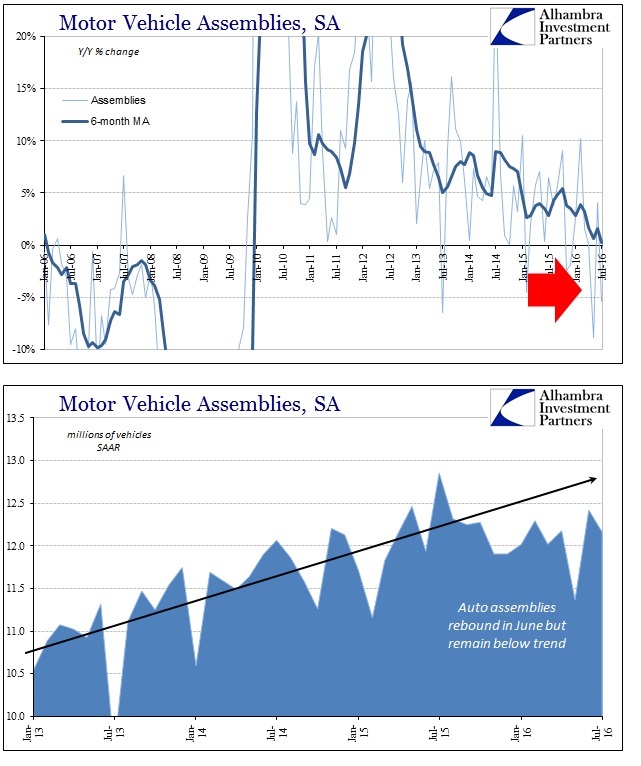

While these results raise serious questions about the demand side and consumers, perhaps the larger and more important economic issue is supply. Ford’s dealer inventory rose to 81 days of supply from 61 last year at this time. That increase on the retail level comes as inventory in wholesale channels remains at Great Recession levels. A sales “plateau” will do nothing to help the inventory imbalance, meaning that there will very likely be negative production adjustments in the near future (more so than there already has been).

“Now the automakers’ focus will shift from simple growth to market share and managing inventories,” said analyst Karl Brauer of Kelley Blue Book. “The use of incentives and fleet sales as a counter to plateauing retail sales will be the statistics to watch going forward.”

With manufacturing overall in the US (and overseas) already gripped by an eerily steady contraction lasting now an astounding two years, what happens in follow-on effects if auto production, perhaps the only steady part of industry in this economy, begins to more seriously pull back as consumers do? It leads even further in the same direction as this economy has been trending, as noted last month when the idea of the “plateau” was first raised.

In other words, the pile up of inventory is quite likely real and to the degree to which it is already suggested and due in some major part to sales not just hugely optimistic overproduction. In macroeconomic terms, it further erodes the mainstream idea of the “strong consumer” particular in comparison to last year which left the economy in a very precarious state despite then far more robust, actual consumer demand for autos (and, I should point out, auto financing). For future considerations, the “plateau” plus a real inventory problem would suggest further that the manufacturing recession may be about to get real.