By Anjani Trivedi at The Wall Street Journal

HONG KONG—Central banks in some emerging markets are stepping up efforts to flood their financial systems with cash, highlighting the pressure that they face from rapid capital flight.

The moves amount to a collective turnabout from months of interest-rate cuts in 2015 that helped send emerging-market currencies down by as much as 20% to 30% over the past year against the U.S. dollar.

The shift in approach was on display last week when India’s central bank left its key policy rate unchanged at 6.75%, after slashing rates by 1.25 percentage points last year. But now, the central bank is pumping more money into its financial system than at any point in the past year by snapping up government bonds and giving banks cash via short-term loans known as repurchase agreements.

Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan said the bank would “use the entire gamut of liquidity instruments” and continue to inject “plentiful” cash into the country’s financial system to counter any perception of a liquidity shortage.

Emerging-market central banks have been increasingly avoiding mainstream policy steps like rate cuts, which can signal deeper concerns about economic-growth prospects, triggering additional capital outflows and more currency weakness.

“Central banks are balancing on a tightrope between keeping monetary conditions accommodative to support growth, but without risking pressure on currencies,” saidSameer Goel, head of Asia macro strategy at Deutsche Bank in Singapore.

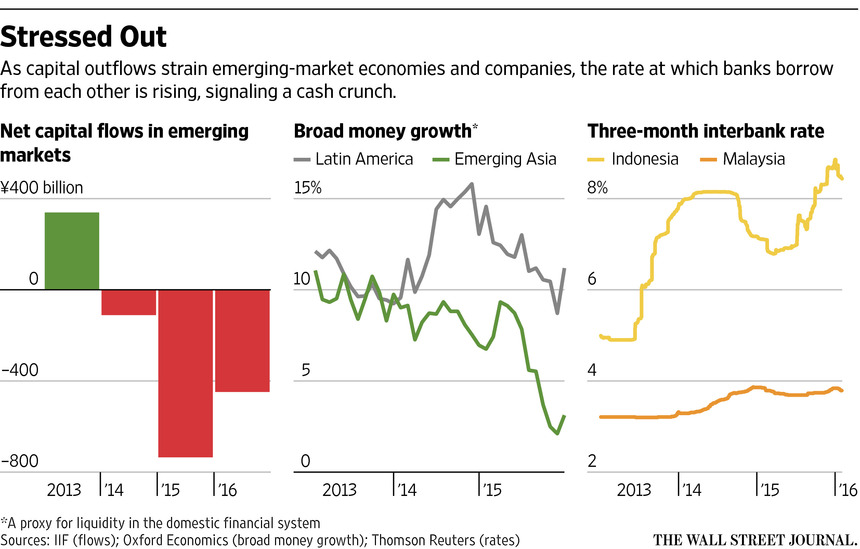

The pressures on these central banks aren’t likely to ease. Over the past two years, a net of more than $846 billion has exited emerging markets and an additional $450 billion could flow out of developing countries this year, according to an estimate from the Institute of International Finance.

Between 2010 and 2014, an average of $1.2 trillion worth of foreign private capital flowed into emerging markets each year, according to the IIF. Last year, these countries collectively saw their first net cash outflows since 1988. In many emerging countries, government revenue from earnings on exports has also fallen—especially for economies reliant on commodities—while deposit growth in banking systems has waned.

Broad money growth, a proxy for liquidity in financial systems in emerging Asia and Latin America, dropped by 3.8 percentage points and 3.4 percentage points over the past year, according to Oxford Economics.

As cash levels dwindle, the rate at which banks lend to each other in some countries has risen. That could threaten the health of already shaky economies as higher costs for banks could spill over to consumers and businesses by pushing up borrowing rates.

The buildup of domestic corporate debt—especially in emerging Asia, where nonfinancial corporate debt to gross domestic product has risen sharply since 2011 to 125% from 100%—is starting to weigh on banking systems. In Asia, companies grappling with declining economic growth and falling commodity prices have seen their ability to service debt fall over the last five years as their debt levels have risen. These conditions have made it more expensive for banks to lend to each other.

In Malaysia, the three-month interbank borrowing rate at which banks lend to each other has spiked to their highest levels in more than a year. Analysts say heavy capital outflows and weak bank-deposit growth there are sapping cash from local financial markets.

Yet with the Malaysian ringgit down by more than 20% against the U.S. dollar in the last two years, it is difficult for the central bank to lower benchmark interest rates further without risking additional currency depreciation. Bank Negara Malaysia spent much of last year defending its depreciating currency by drawing down its foreign exchange reserves.

Earlier this month, the country’s central bank instead cut the ratio of reserves banks must hold at the central bank to 3.5% from 4.0%, in an effort to free up capital for more lending. In the past, it has used this tool only at times of heightened global stress, like in early 2009, during the global financial crisis, and also during the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s.

Policy makers are addressing rising funding costs in the banking sector on an ad hoc basis. “It’s been a lot more reactionary than proactive. You’re seeing capital outflows so they’ve come out with these measures,” said Rahul Bajoria, a regional economist at Barclays in Singapore, referring generally to emerging markets in Asia. “There’s very little monetary policy room in these economies.”

The International Monetary Fund’s Christine Lagarde on Thursday called for “a stronger international monetary system” that would include a more robust set of tools for authorities in times of crisis.

China’s central bank has also been trying to lower the strain on its financial system without further rattling investor nerves about its economy and currency. The People’s Bank of China injected the largest amount of cash into its financial system in nearly three years last month.

The Wall Street Journal reported last week that the PBOC recently decided not to use a traditional credit-easing tool that would require banks to hold less cash in reserve for fear it would send too strong a signal that it was easing policy. Instead, the PBOC injected about 1.8 trillion yuan ($274 billion) into the country’s banking system in the last two weeks using short and medium-term loans to banks.

Late last month, National Bank of Hungary Vice Governor Marton Nagy said the bank would likely keep its main rate—which is already at a record low of 1.35%—unchanged for several months. Instead, Mr. Nagy said the central bank would likely fine-tune other policy tools, including by adjusting the rates at which it lends and takes in deposits overnight from banks.

“In normal times, when we see central banks cutting reserve ratios and conducting open market operations, we equate them with easing,” said David Hensley, head of global economic research at J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. in New York. “In times of stress like these, he says such measures are “merely an attempt to maintain the status-quo.”

Source: Emerging-Market Central Banks Battle Capital Flight – The Wall Street Journal