Last week I gave you a run down on the bad news on European banking system data. Now, for the really bad news, here’s a look at the weak sister countries in the system and some broad data, which shows just how widespread and scary the numbers are. The problem is that Europe’s banking system is the biggest in the world. And QE and negative interest rates (NIRP) have, at best, only stabilized a terrible situation.

That’s the real reason the ECB continues to print money hand over fist. The real purpose isn’t to stimulate the European economy. The purpose is not to trigger inflation. Draghi knows damn well that NIRP and QE can’t do that. Actually NIRP is destabilizing, but that’s a discussion we’ve had repeatedly, so we won’t go into detail on that again. Suffice to say that NIRP doesn’t encourage lending. It drives money out of the system altogether. It does so by encouraging depositors to extinguish deposits by paying off loans. And it motivates institutional depositors to simply move their money out of Europe. Big help to the US–to Europe, not so much. In fact, it’s a disaster.

No the real purpose of the ECB’s desperate money printing is to stave off systemic collapse. Because Draghi knows that if he stops printing Europe’s banks will collapse. And they’ll take everybody else down with them.

And so, ladies and gentlemen, after presenting you with the best of a terrible lot of European bank data last week, I now bring you the horror show aspects.

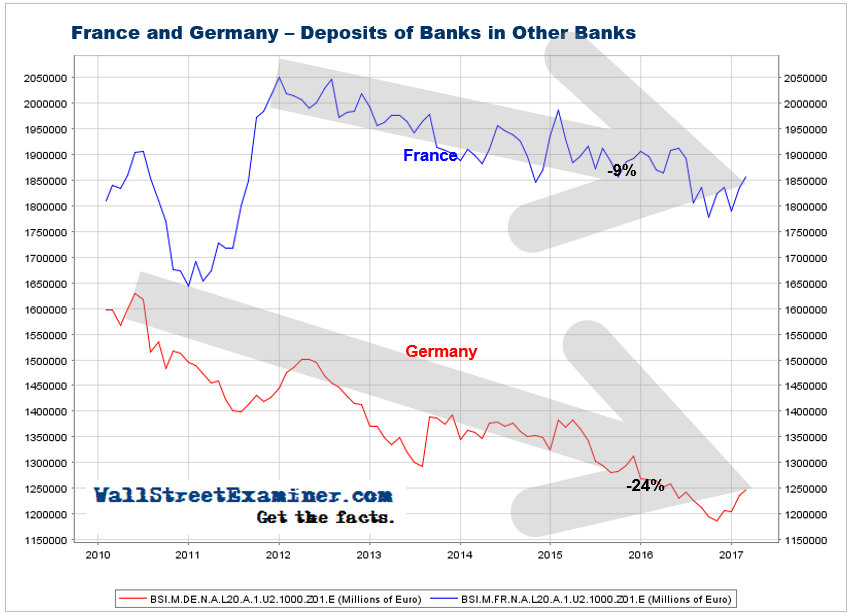

First here’s the trend of deposits of banks in other banks. Just as I predicted they would when NIRP was instituted in 2014, banks have been extinguishing deposits ever since. And where has that trend been strongest? In Europe’s largest economy and banking system, Germany.

These deposits in France and Germany rose in February. It was the second straight uptick coming off a trend low. But this still isn’t close to reversing the downtrends.

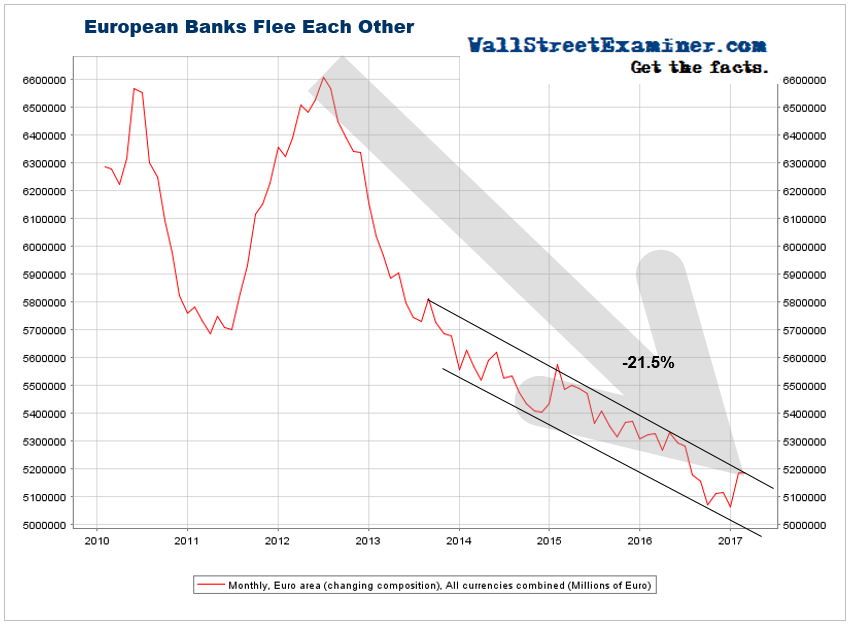

The downtrend total deposits of banks’ own funds in other European banks is still in force in site of a dead cat bounce in January. It died again in February.

Banks in Europe simply don’t want to hold their own funds in other banks. They know just how risky that is.

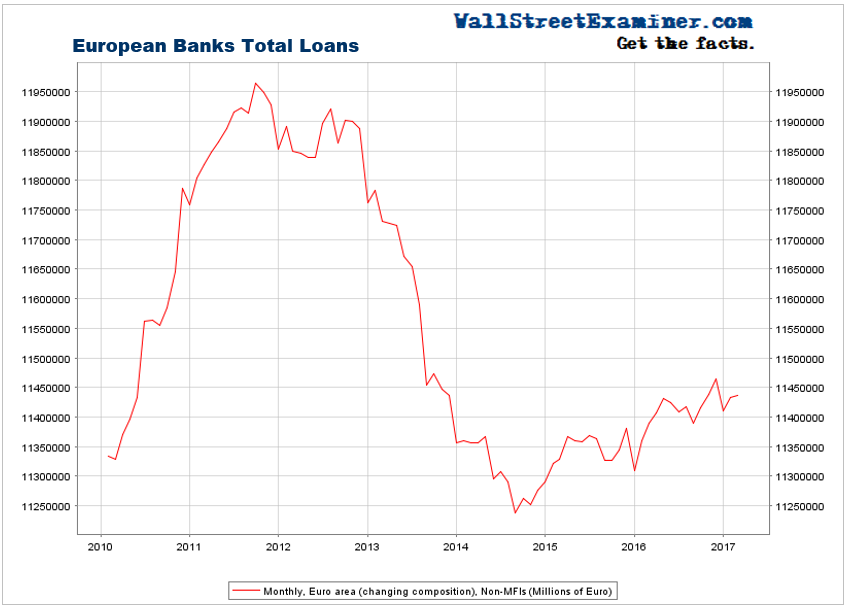

Meanwhile, in spite of all the central bank money printing and crazy schemes to get banks to lend, loan growth is moribund. There’s not much loan demand, and banks don’t trust borrowers to pay them back anyway.

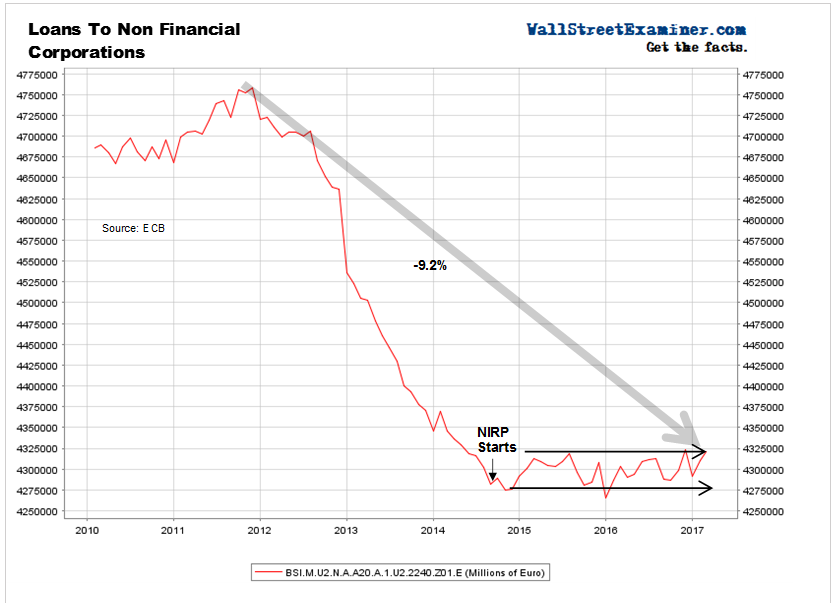

Total bank loans rose by €3 billion or 0.03% in February after rising by €25 billion or 0.2% in January. The year to year growth rate was a rip roaring 0.4%. The total outstanding is still down 4.4% from the 2011 peak. It is also below last year’s peak, reached in November. It has gained only 1.5% since the ECB began imposing negative interest rates (NIRP) in September 2014 (announced in June 2014). The policy has utterly failed to stimulate credit expansion.

Outstanding loans are just one misstep away from outright contraction.

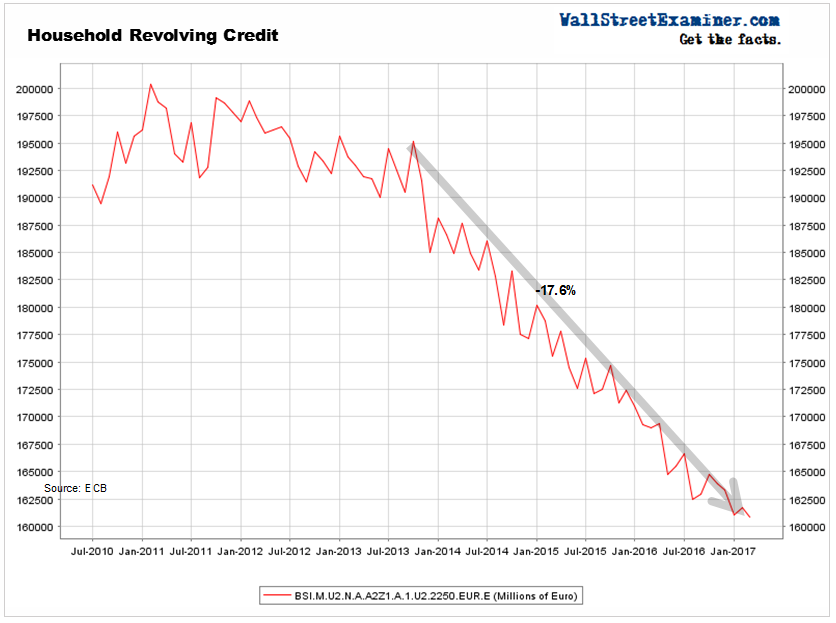

The gains have been entirely in household borrowing. After being flat in December and January borrowing rose 0.3% in February. It was up by 2.2% over the past year and up by a total of just 5% since bottoming in May of 2014. An annual growth rate of 2% has held steady since October of 2015.

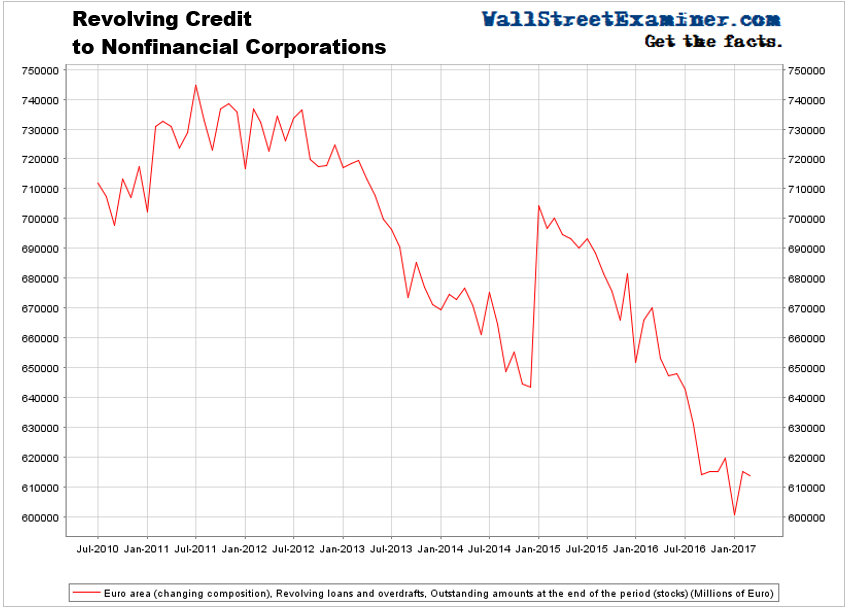

This is weak growth, indicating that few Europeans want to borrow regardless of how low rates are. Europeans have no confidence in their economies. Household revolving credit remains in a death spiral, falling 0.6% in February to a new low. The year to year decline is -4.8%.

Business loans to nonfinancial corporations are similar to the Commercial and Industrial Loans stat for US banks. They rose by 0.3% in February, growing at the same rate as in January. The annual growth rate is 4.2%. However the total outstanding is still within the range of the past 2 years. Since NIRP was instituted, the total of these business loans has grown by €33 billion on a base of 4.29 TRILLION. That’s an increase of 0.8%. Not a lot of mileage for 2 ½ years of negative interest rates and a couple of trillion in QE.

Business revolving credit downticked slightly in February after a dead cat bounce in January. That came after a plunge to a new low in December.

The total loss since the data was adjusted at the beginning of 2015 is now 12.8%. It’s a sign of just how little confidence European businesses have in the economy there. As the European banking crisis flares up, credit liquidation accelerates, destroying capital. That’s a bad thing, not just for European markets but for the US as well.

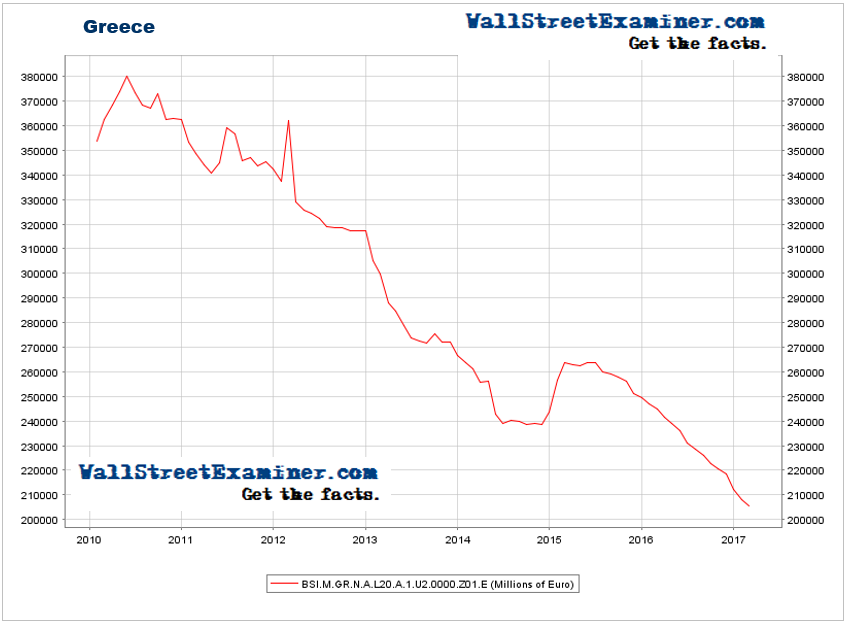

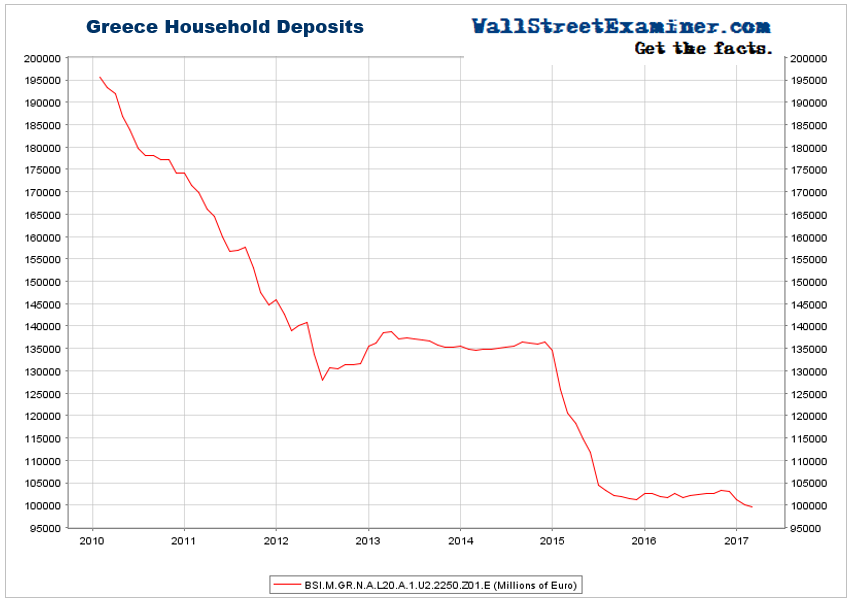

Following is a review of total bank deposits in the most troubled European national banking systems. Dwindling bank deposits are evidence of weakening economies, declining population, and just plain people getting poorer. They are also evidence of people moving to “black money”–cash trade, to avoid punitive taxation, particularly in Greece. Having spent 3 months in southern Europe in both 2016 and this year, I’ve seen the hardship first hand. I see no reason for hope that these trends will reverse.

Household deposits in Greece have now fallen below €100 billion.

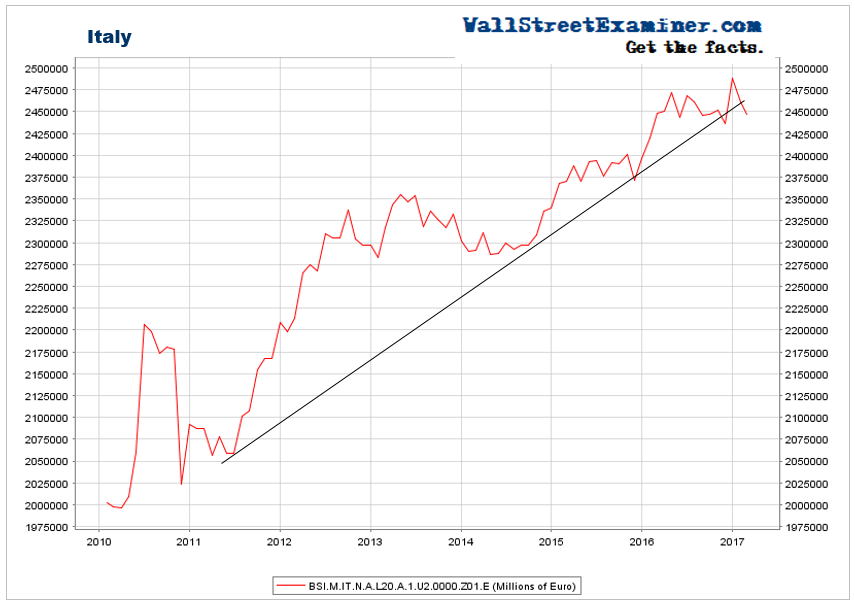

Deposits in Italy pulled back in February for the second straight month. They are now on the verge of breaking a 6-year uptrend. They had broken out to new highs in December. That breakout was immediately reversed. The ECB has been aggressively buying Italian bonds and pushing the money into banks there but it has done little more than stabilize the situation.

If any country must kick the can down the road, it’s Italy. As their bad loans have grown to gargantuan proportions, so have the deposits back by those worthless loans. Italy has over €2.4 trillion in deposits. Deposits in Italy pulled back in February for the second straight month. They are now on the verge of breaking a 6-year uptrend in spite of the ECB buying massive amounts of Italian government bonds.

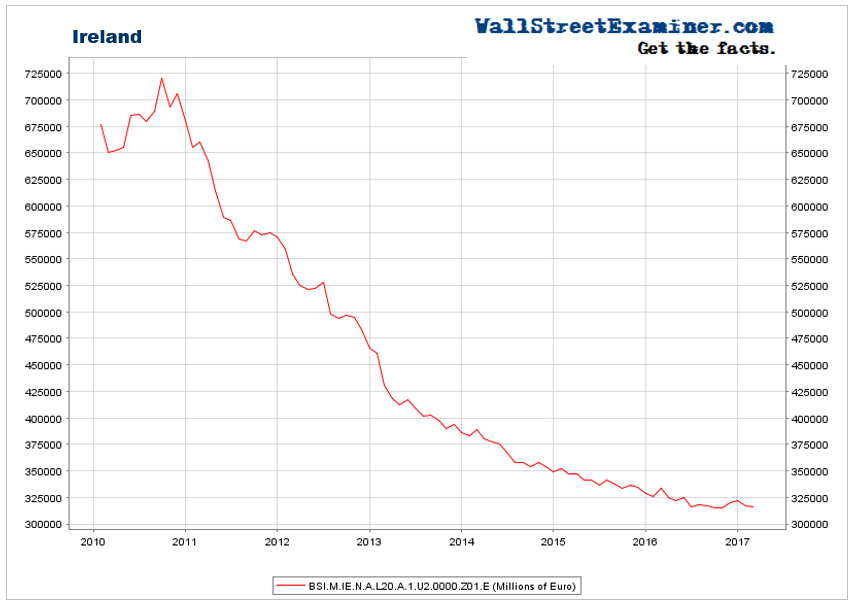

Deposits in troubled Ireland have stabilized since May. But there’s no sign of recovery.

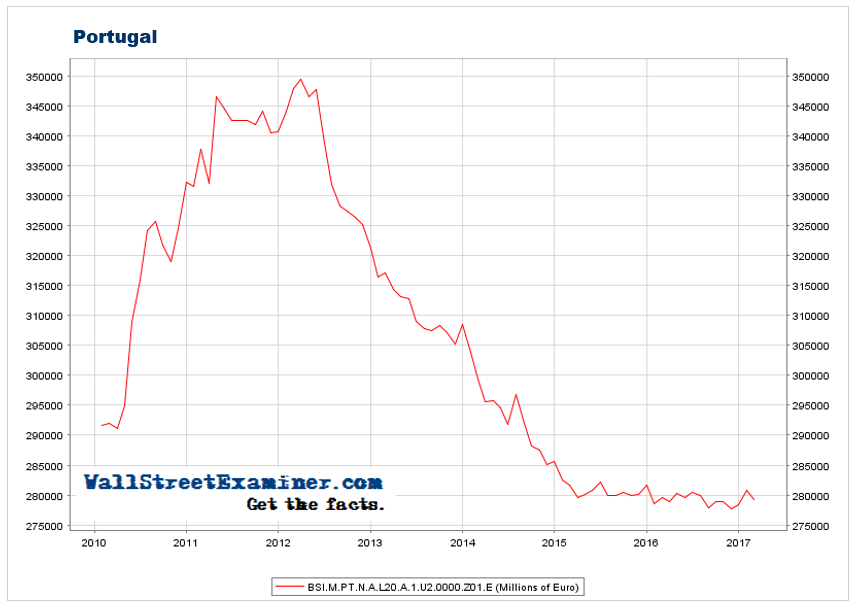

Deposits in equally troubled Portugal downticked in February. The trend is still dead in the water. Here again, there is no sign of recovery.

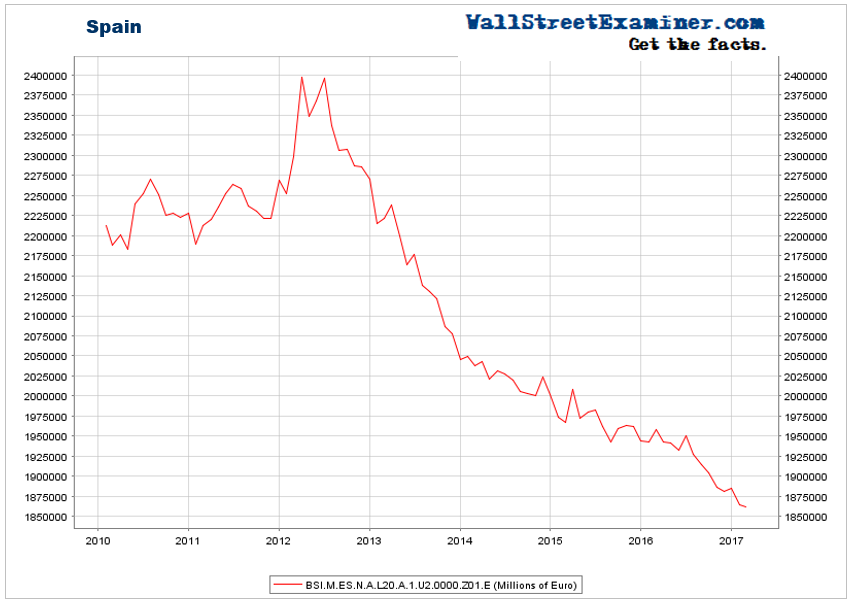

We’ll end this tale of woe with the Eurozone’s fourth largest economy, Spain. It has lost a quarter of its deposits in the past 5 years and there’s no sign that the trend is even softening.

The data makes it clear that Mario Draghi’s desperate attempts to shore up the system aren’t working. But he keeps buying. My question is this. What happens when the ECB owns all of the fixed income paper in Europe, and European banks still have no money? That’s a lot of printed money down the drain. It has either been extinguished or it has left the continent.

I’ve heard some pundits talking about putting investment money to work in Europe because it’s cheap. I’d rather spend my money in Europe, than invest it there. Investing there still seems like a fool’s errand. I wouldn’t invest a dime there until there’s light at the end of the tunnel. All I see is darkness.