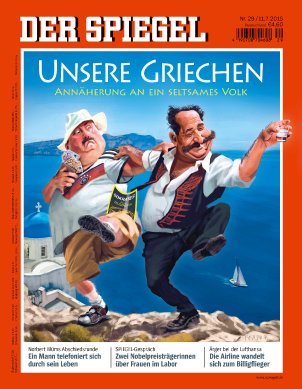

Der Spiegel has a long analysis today on the fate of Greece and the Tsipras/EU pas de deux. The tone toward Tsipras seemed secretly admiring while outwardly scornful and hostile. He comes off ultimately as the bad guy who is completely and solely to blame for the worsening crisis, with Merkel and EU bureaucrats portrayed as earnest leaders who badly miscalculated the situation and misread Tsipras.

Der Spiegel has a long analysis today on the fate of Greece and the Tsipras/EU pas de deux. The tone toward Tsipras seemed secretly admiring while outwardly scornful and hostile. He comes off ultimately as the bad guy who is completely and solely to blame for the worsening crisis, with Merkel and EU bureaucrats portrayed as earnest leaders who badly miscalculated the situation and misread Tsipras.

Spigel simplistically summarized the views of the two sides:

From the Greek perspective, the EU, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the euro zone are all synonymous with poverty and exploitation. From the perspective of most European Union leaders, on the other hand, Greece is little more than a failed state governed by clientelism and nepotism, a country whose economy has little to offer aside from olive oil and beach bars.

Then it blamed the current Greek regime for exacerbating an already bad situation.

But relations between the Greek government and its partners in the 18 euro-zone capitals are deeply impaired. The Greek economy’s slide has dangerously accelerated under the new government and Brussels has lost almost all of its trust in Athens.

The Spiegel team went on to heap a litany of blame on the Tsipras regime.

Tsipras’s leftist-nationalist government has not done much for the economy. In the six months since the election, Greek parliament has done little to simplify the tax code as promised or to streamline the country’s bureaucracy. Furthermore, the man in charge of promoting international business relations in the Foreign Ministry is a cousin of Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras. But instead of boosting exports, he has primarily drawn attention to himself with his rhetoric of class struggle and his chastisements of Europe.

They apparently had little difficulty finding Tsipras critics within Greece.

From the perspective of Athens-based economist Aristos Doxiadis, Tsipras’ policies are akin to an all-out offensive on his own country’s economy. The prime minister, he says, is effectively driving companies and highly trained workers out of Greece…

…In the offices of the German-Greek Chamber of Industry and Commerce, the mood is terrible, almost as though the Grexit had already taken place. One of the chamber’s tasks is that of attracting German companies to do business in Greece. But the chamber’s head Athanasios Kelemis says he can’t, with a clear conscience, advise anyone to invest in his country.

The EU leaders are apparently all earnest, honest statesmen (and woman), faced with dealing with an unscrupulous scoundrel.

The EU heads of government are furious that he came to Brussels without a new batch of proposals. Luxembourg’s Prime Minister Xavier Bettel says that his trust in Tsipras has been destroyed because the Greek premier keeps saying different things in Athens than he promises in Brussels. “I am disappointed,” says Bettel.

Tsipras is confronted by irritation from all directions. Mark Rutte from the Netherlands, Dalia Grybauskaite of Lithuania and Robert Fico of Slovakia are particularly drastic in their choice of words. Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat says that, 14 days ago, he would have been prepared to sign any agreement, but that now he is fed up with Tsipras’ stalling tactics.

Those who placed a great deal of faith in Tsipras in recent weeks are particularly frustrated, chief among them Commission President Juncker. Over and over again, Juncker sat down with Tsipras, spoke to him on the telephone and offered him concessions.

Now, though, he is forced to watch aghast as Tsipras is celebrated like a gladiator during an appearance before European Parliament [as]…he once again launches into a long diatribe, complaining that the austerity measures thus far imposed on his country have resulted in a “spiral of recession and deeper depression.”

Spiegel sees Greece’s international creditors blaming Tsipras and falling into disarray.

They see the situation as follows: Much had improved before Tsipras took over the government, to the point that national revenues had finally exceeded spending. But the Tsipras government loosened up the austerity regime, unsettled the business sector and consumers with contradictory announcements, and refused to privatize state-run enterprises. “The political changes since the beginning of the year have led financial requirements to once again increase enormously,” the International Monetary Fund wrote recently in a report.

A Poisonous Conflict

Now, the country’s budgetary figures have worsened dramatically — and Greece’s creditors have begun bickering among themselves as to the conclusions that should be drawn as a result.

There’s a lot more to this piece, including analysis of preparations for Grexit, and where those poor EU leaders went wrong, including this excuse for Mrs. Merkel.

Merkel’s goal was long that of keeping Greece in the euro zone. And fundamentally, that hasn’t changed. A Grexit is would be extremely risky and Merkel is a politician who seeks to avoid risk at all costs. For a long time, she saw the negotiations with the Greeks as being consistent with the typical decision making process in Brussels: tough negotiations with a room full of vain men capped by an 11th hour agreement. Merkel knows the procedure well, and has often emerged as the victor.

But the chancellor misjudged Tsipras. The man is a gambler and he has little respect for the complicated mechanisms of European consensus-building, without which the European Union cannot function…

…Tsipras’ politics are “hard and ideological,” a frustrated Merkel recently complained in a meeting of Christian Democratic Union (CDU) leaders. He is steering his country into a brick wall “with his eyes wide open.”

With Spiegel, the German version of the New York Times and Washington Post rolled into one, heaping this much opprobrium on Tsipras, it seems to me that he must be doing something right.

Read the Der Spiegel report The Fate of Greece: Decision Time for Tsipras and Merkel