The amount of credit market fireworks this week is only surpassed by those of October 15. Everywhere you look, credit markets are not just growing bearish but, as I said earlier in the week, bearish in comparison with past crisis periods. The past few days have surpassed even that observation, making credit now a fast-moving indicator of still nothing good.

For most people that makes sense of Europe. The currency bloc that has been strangled by the common euro is living up to that sense of monetary reality. All that talk of recovery only eight months ago has been washed away in a tide of remarkable fear. What was perhaps only unease or mild nervousness as late as September has turned in the past few weeks to what can only be described as growing desperation.

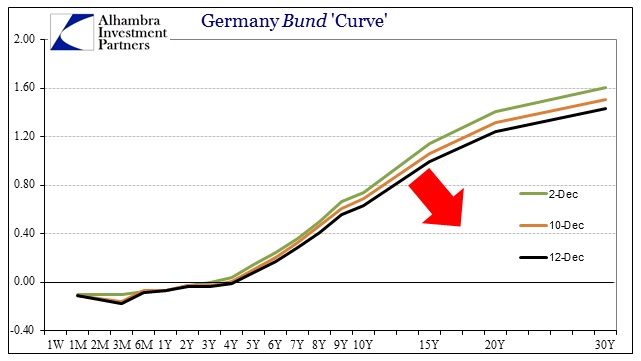

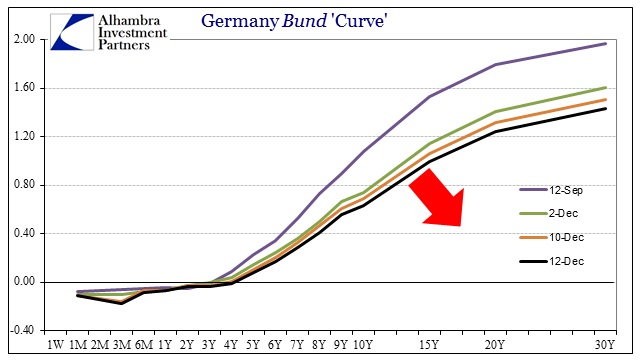

Just this week, the German bund curve at the longer end has dropped 10-15 bps all the way out. The 15-year bund is now under 1%! The benchmark 10-year has fallen all the way to an essentially meaningless 63 bps. That is an astounding drop of 44 bps going back to mid-September.

You may recall mid-September for its break in this bearish action that started back in August. At the time I believed that minor reprieve was related to optimism over the ECB’s ABS plan and covered bond purchases that finally offered something specific apart from the usual bland platitudes of “promises.” Of course, since almost nobody even remembers that now, its total lack of efficacy has been made plain with the ECB looking far worse and even more (if that was possible) impotent for their trouble. So in the midst of what was forewarned as a major monetary “stimulus” credit market revulsion is severe; an exceptional result unlike anything of the past five years, especially the last three.

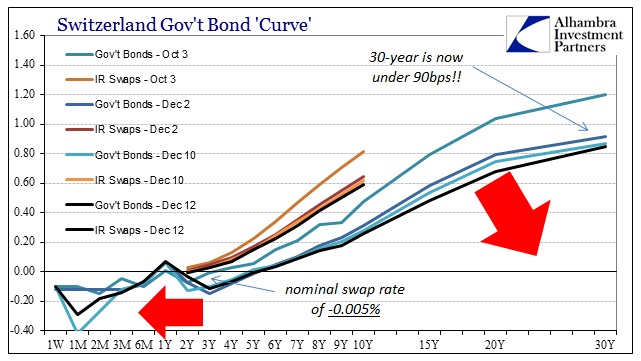

The same has been rendered in Switzerland, as action this week and the great moves since the end of September leave the bond curve there in an obvious signal of distress.

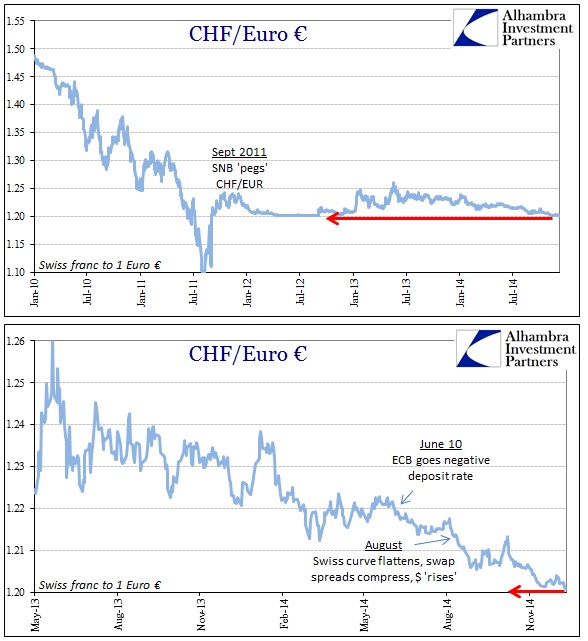

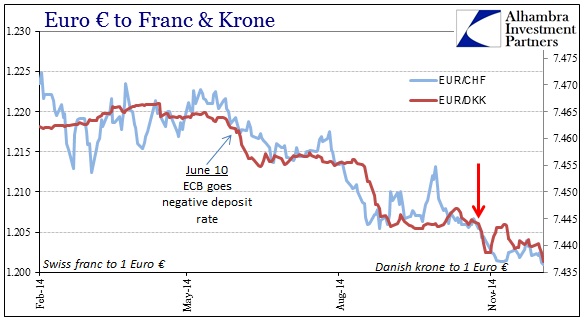

With swap rates falling too, and spreads flattening out, it seems as if the derivative market is almost confused as to what to expect. The cash market is moving quickly and now the franc is seriously threatening the euro/franc peg.

The last time the euro/franc cross was this close to 1.20 was the middle of 2012, when the euro crisis was roiling pretty much everything in Europe (which is why so much similarity now is deeply concerning).

Again, it is not just the franc showing a determined bid for safety from the euro, the Eurozone economy and the ECB, but also the Danish krone. The krone, like the franc, has appreciated to a level not seen since the darkest days just prior to Draghi’s promise to “do whatever it takes.” So everything we see here is related to that still-unspecified and untested remark unwinding without ever having gained much in the economy, or really in financial “normalcy” (see: Greece).

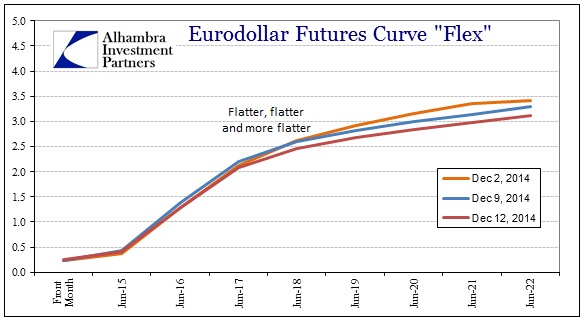

But that is Europe; the US is supposed to be completely different. If you judge by credit markets, the US may, in fact, be in worse shape. Starting with funding markets, eurdollars have traded like German bunds and Swiss bonds drawing ridiculously flatter just in the past week.

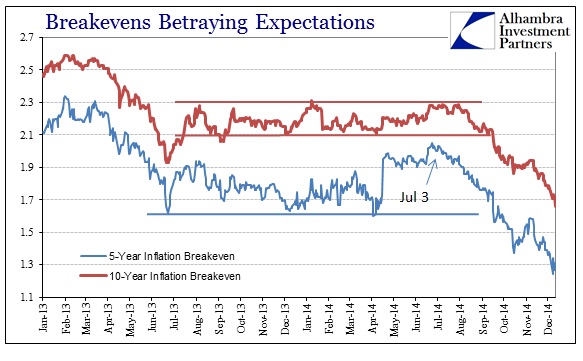

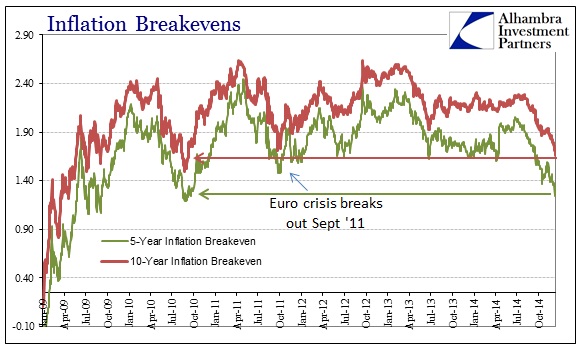

With the front end of the curve essentially cemented by the FOMC’s stated intent on ending ZIRP, there is no “dollar” relief here only continued bearish expression. That reverberates all across “dollar” credit as the worst of everything – no reprieve (from the market’s perspective) on policy and continued downgrading of economic assessments and perceptions. With breakevens having now surpassed the 2011 crisis lows, it won’t be too much longer (if this 13-month trend continues) until they join the flat treasury curve in comparison only with the Great Recession.

Even the FOMC’s preferred measure of “market-based” inflation expectations, the 5-year/5-year forward implied rate, has dropped considerably and now faces the same kind of dreaded interpretations (as in not too enamored with the ridiculous idea of oil price = “stimulus”, but rather in complete agreement with oil price collapse = economic downdraft).

Given all this tandem information spread across vast geographical distance and trillions upon trillions of the largest credit and funding markets ever conceived, it is difficult to come to any interpretation other than the fact that credit markets have declared the recovery as being over, done; dead and buried. Maybe QE5 can entertain a revival, but given that QE3 & 4 are not so far in the past as to be irrelevant to this situation, it may not have that much positive effect next time. At that point a QE5 may only just confirm what credit markets already know, and what perhaps stock investors are starting to gain at least some introductory awareness.