The problem with Brazil is that its central bank has done everything the monetary textbook requires of it. Setting aside that Banco itself is a literal mishmash of public and private interests (what central bank isn’t?), the freefall in the Brazilian economy of late is simply puzzling to the mainstream. Unlike the US or Europe, at least the descent is being recognized openly, no weather excuses or residual seasonality here, but even that has been shocking in now both the scale and perhaps more importantly the time.

The latest figures from Brazil paint a Great Recession kind of picture for the country, except that this massive depressiveness has been working up in steadily gaining contraction well over a year now. By orthodox “rules”, that isn’t supposed to happen especially where the central bank follows so closely monetary direction. No matter what Banco has tried, the sinking plane of economic reality remains unrelenting. The proportions now in the latter part of 2015 have become staggering:

The Central Bank of Brazil’s IBC-Br index, a monthly proxy for gross domestic product, showed economic activity fell by a 6.2 per cent in September from the same period a year earlier.

That’s the biggest year-on-year drop on record, according to Capital Economics, and points to a third quarter contraction of nearly 5 per cent.

Economists simply don’t know what to do about it. An economic system is not supposed to undertake a slow motion collapse.

A quarterly contraction would be the third in a row for Brazil. The economy shrank 0.7 per cent in the first quarter and another 1.9 per cent in the second.

With Brazil’s economic and political crisis showing little sign of abating, economists have been busy revising down their already gloomy forecasts for Brazil’s economy in recent weeks.

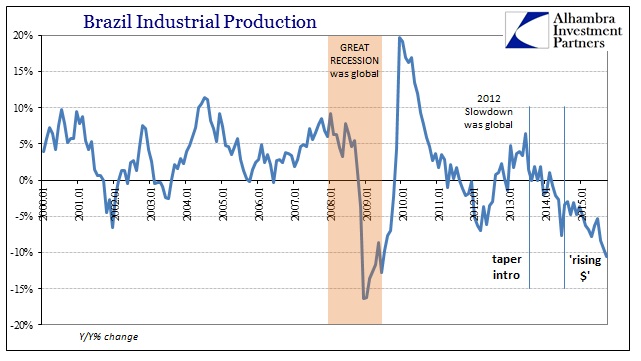

Recent economic accounts apart from GDP have set those expectations. The data is well beyond grim; industrial production has contracted for 19 consecutive months and 21 out of the past 22. Year-over-year IP fell almost 11% in September which isn’t distinguishable by proportion from the worst of 2009.

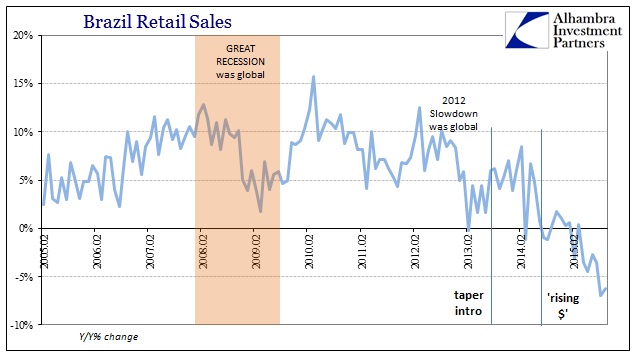

Retail sales fell by 6.2% Y/Y in September after subtracting almost 7% in August. The 6-month average is now almost -5% marking already a much worse retail circumstance than any of the Great Inflation.

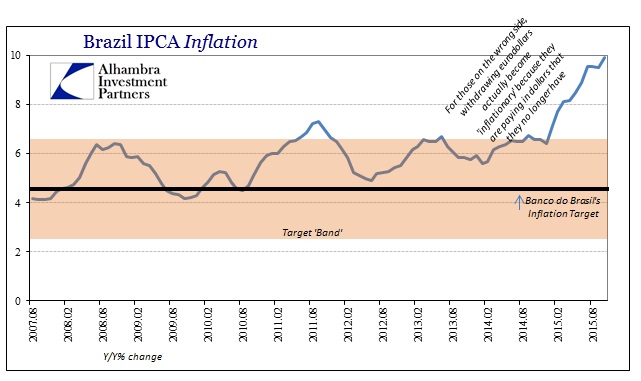

While economic transactions and production volume are in total freefall, “inflation” is out of control and only getting more so. The latest IPCA estimate for consumer price inflation for October was 9.93%, and estimates for November are already running at 10.5% if not 11%. With “demand” supposed to be the heavy component of inflation, the contradiction is glaring leaving only finance to fill out the explanation.

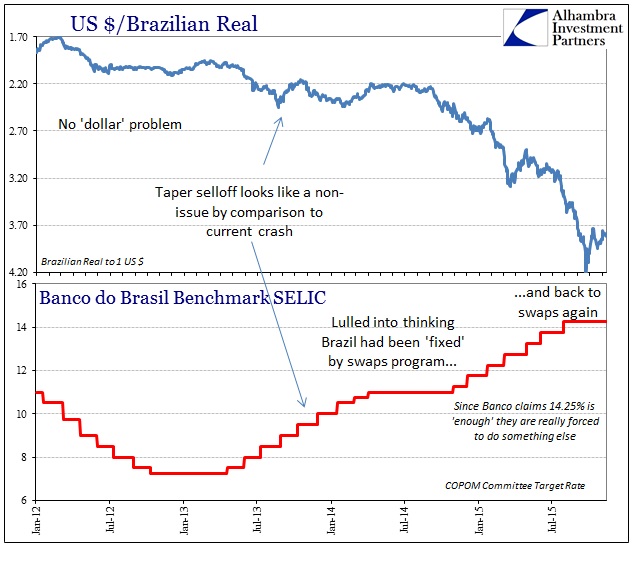

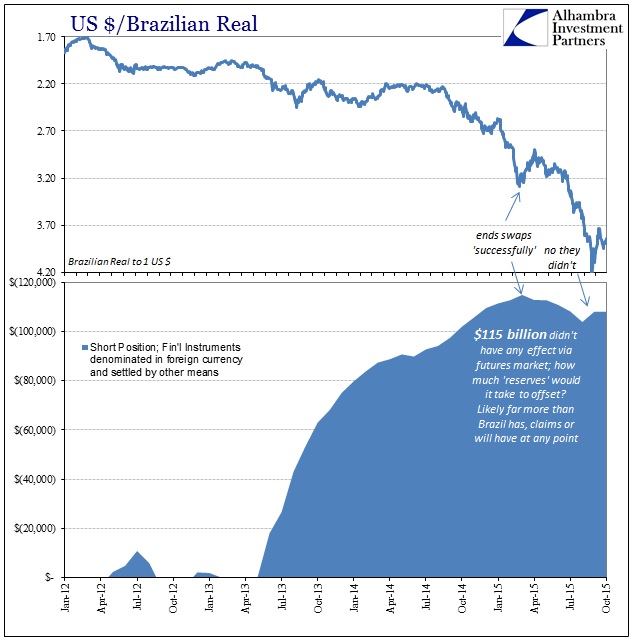

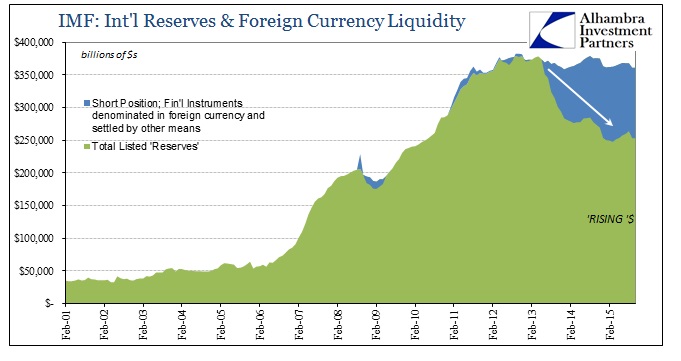

By the book, Brazil’s central bank has done everything that economists demand, attempting to stop the currency’s devaluation with interest rates and “swaps” references. They have threatened to mobilize the nation’s dollar “reserves” (even though the “swaps” already did), and still nothing has stopped the wholesale currency destruction.

In fact, the accumulation of a huge short liability from Banco’s wholesale interjections starting in 2013 forced the central bank to earlier this year give up on the program altogether – but not before declaring it a glowing success even though the real had by then sunk unthinkably below 3 to the dollar. It was $115 billion in activity for a huge and costly collapse anyway. With another massive wave of devaluation again in the summer, Banco has performed a reflexive rethink and has re-entered the wholesale manipulation.

Having already “eaten” through almost a third of their “reserves” and with the benchmark repo rate, SELIC, already above 14%, what else can they do? Despite all that, the economy remains as the currency, both hurtling along to obliteration. There is great difficulty in overstating the economic chaos from that, as industrial production, for example, having suffered this extended and accelerating decline is now at levels seen more than a decade ago! Unlike then, however, debt levels over that decade had blossomed with what was viewed conventionally as a permanent accretion of wealth and economic status.

The basis for that financial devolution was never actual, sustainable economic gains but rather as a byproduct of the wholesale “dollar” running freely throughout the globe. The Brazilians were borrowing “dollars” they didn’t have in order to fund production based on “dollars” (largely, but not exclusively, running through China). The circularity was mistaken for organic progress because nobody wanted to reveal the canard; economists themselves were only too happy to ascribe that “success” to their own great intellectual feats. It was nothing more than dramatic impoverishment at the hands of the eurodollar.

When you pay for something with money you don’t have, you are risky to begin with. When the money you don’t have becomes suddenly less freely available, you have to pay up for the ongoing privilege; and when paying up leads inescapably to more visible difficulty you have to pay up yet again, the inexorable downward spiral being what we see now in Brazil. The real is just such an indication of the cost of attaining “dollars” in order to remain economically active in the global “dollar” system. This is the difference of a credit-based global reserve currency regime, only in 2015 the magnitudes have expanded even from 2009.

Thus, the real is only different from renminbi and even francs in its leading edge position. To varying degrees, this is the fate that awaits without some paradigm alteration to pick up the “dollar’s” weight.

Economics doesn’t see it, but despite all the complexity, jargon and foreign if not counterintuitive concepts of wholesale finance, in general terms this is nothing that we haven’t seen before. It is fractional lending being practiced globally only without anything specific at its core as a matter of base convertibility; a bank run without the traditional bank; a money squeeze without any money; a popular wave of irrationality, sort of, without any people to do it, only institutions themselves. In short, it is a run with all the dirty and disastrous economic consequences of it. The fact that you cannot pin down exactly what is being run and for what convertibility chain (balance sheet factors freely and relatively cheaply offered, but which ones?) only makes it unnervingly difficult to suggest how to stop it; the unmistakable character of it, by contrast, leaves little to the imagination about how it ends.