The growing appeal toward unease about the terms of Greece’s ongoing strangulation is more than just a simple, fleeting sense of déjà vu. It is exactly the same process only pushed forward three years. At the height of the “last” challenge that began in earnest in 2010, and nearly re-ignited a global bank run (among only banks) for a second time by December 2011, was this game of chicken between the Greek government and the “troika.” The governments have changed on both sides, but the game remains “unwon.”

Ostensibly, this is supposed to be about a fiscal imbalance in the government redistribution mechanics under the euro. However, I don’t really think anybody actually believes that as the problems are far, far deeper – to the point that banking became all-consuming not just in Greece but all over Europe (what was the point of the LTRO’s, nearly a trillion euros “worth”, if not to grease the skids of any Greek-driven discussions?). Despite the idea that banks operate credit policies under “fundamental” regimes, European banks across the continent “found themselves” ditching US MBS “products” in favor of all manner of “undervalued” (in light of coming central bank activities) sovereign debt – PIIGS and all.

It has always been a problem of financial imbalance. In the closer senses of 21st century financialism, the economy is malformed and therefore doesn’t create enough quality collateral by which to keep the entire plumbing network from disastrous dislocation. The LTRO’s gained much of the attention, but where Greece was concerned it was the OMT’s and especially the “waiver” of collateral rules allowing Greek government debt to remain eligible for ECB funding (a waiver which was just recently revoked as the game of chicken escalates once more) that contained the spread of illiquidity as it sought nothing short of insolvency revelation.

That is what collateral shortage actually means, if you get down to the naked truth of it. Lending that took place against damaged or deficient collateral is essentially the liquidity facet of insolvency. Central banks have aimed, squarely, to circumvent that self-correction by inserting their own balance sheets into that financial “equation” whereby they are no longer the “lender of last resort”, but both dealer and eventually “market of last resort.” The goal is simply to change the “market” price for damaged collateral so that any insolvency is delayed until more “favorable” conditions eventually appear – and then what looked insolvent is hopefully no longer.

The historical and theoretical foundation of that approach is not just the 19th century sense of “elasticity” as argued by Bagehot and others, but rather the span of the 20th century as orthodox economics, especially monetary economics, began to turn totally against markets of any kind. Given the modern role of central banks as to economic commandments, markets are just too messy and the central bankers are tired of “cleaning up that mess” under political pressure. They instead turned to circumvent the process by “filling in the troughs without shaving off the peaks.” Unfortunately, “shaving off the peaks” almost always takes the financial form of impaired prior debt and the eventual and very much related “death of money.”

That sense of powerful entitlement turns everything that happened in the latter decades of the 20th century upside down. And that starts with the end of fixed exchange.

The entire point of floating currencies was to remove any block or impediment to clearing large and dangerous imbalances. By the 1960’s, gold came to be viewed under such terms as it was thought, especially by those in London and Chicago, that the true gold standard was restrictive and therefore not only failed to remove imbalance but amplified it. That sentiment has come dominate monetary thought – which is why gold is so reviled at the official levels.

You cannot speak of floating currencies without appreciating Milton Friedman, who argued most especially in favor of them. That appreciation is a double-edged sword, however, in that there is much to admire in both the position of Friedman’s advocacy and also his scholarly innovation and diligence. That being said, there was far too much deference on the part of Friedman and his fellow proponents toward giving up on markets and how that would be “resolved” by future policy iterations that had little appreciation for them.

The key to understanding this change, and why Greece is where it is, resolves to the various types of floating currency systems. Friedman advocated for either a fixed exchange with discretionary internal monetary policy (as the former would reign back the latter) or the reverse (a fixed internal monetary policy with a floating currency). In his mind, and I think academically this made a lot of sense, there had to be a market mechanism to act as a release against the buildup of unsustainable pressures.

Unfortunately, these were not the only methods of attaining a floating currency regime and ultimately it was beyond naïve to expect that the temptation would kept at bay for long (and it wasn’t). As the soft central planning of the 1980’s became the dominant factor in monetary activities, neither the currency end nor the internal monetary policy were much apart. I doubt anyone would successfully argue that the Plaza Accord kept with the spirit of what Friedman was searching for as a true alternative to gold that kept at least some market aspects. The true gold standard wasn’t anathema to markets, it was the very means by which they would be respected; something that takes place less and less as yield curves all over the world shrink and shrink.

In other words, political forces infiltrated both sides of the “floating” equation such that financial imbalances were not just evident, they became intractable as a feature!

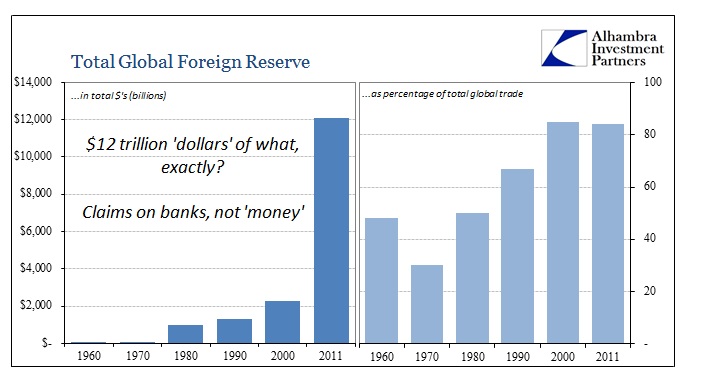

The rise of globally-held “reserves” starting under the floating regime is not the perfect means of protection against any short burst of illiquidity, but a representation of the very means by which imbalance is gaining immensity. “Reserves” are not piles of cash stored in a vault, but a bank liability that is and has been traded endlessly. That means that even global trade has come to be dominated by lending and debt (though the global “dollar” short has shown that even global trade mechanisms under the floating terms were just another outlet for imbalanced speculation).

Greece’s problem is this very setup, as financialism and imbalance ruins the mechanism by which currency fixation would step in; except in Greece’s case, the currency (the euro) was the very means by which financial imbalance must exist. The floating currency as Freidman expected should have dispelled the financial imbalance long before it attained existential status, but the actual and “flexible” design of the controlled monetary economy of current central banking instead actively sought greater and greater financial imbalance as a means of continued operation. It is totally upside down.

Of course, some of this argument about the domestic piece of the floating currency setup is moot to begin with, in my opinion. The ability to hand discretion to a central bank invalidated even the regime Freidman envisioned as most likely to succeed – again, because he saw central banks as agents of “market” activity, perhaps at most intrusively reasserting price “balance.” As we know all too well, central banks have taken this floating currency “flexibility” about as far as it possibly could be stretched, to the point that neither markets nor currencies are respected – or even apply (especially in the case of collateral).

For Greece to succeed, they need to break the ceiling imposed by the euro and the domestic monetarism that makes it a noose. To restore banking would mean to restore true collateral creation which is a real economy factor, not some monetary conjuring. But to gain true acceleration means a break from prior imbalance, which, at this extreme moment, calls for nothing short of a debt jubilee – ironically, something that Milton Friedman himself noted as the historical “cure” for past imbalance.

That is the irony of this “floating” currency regime, not just in Europe but almost everywhere. It was supposed to free domestic financialism from the “shackles” of gold in order to not repeat the Great Depression. Instead, as in Greece and broader Europe, monetary conditions are as tight as they were in the early 1930’s – interest rates and yield curves announce and denounce once again the death of “money.” That is why Greece is locked in place, seemingly at the same point at which all this started despite the passing of almost five years now! That is a damning indictment, as the passage of so much time is not cost-free, instead the opportunity cost of lost compounding of an actual recovery is now far, far greater than any short-term disruption that would be caused by a jubilee or default.

Is it better to take the severe disruption and make your way through the short-term disaster, or to be locked into economic purgatory for economic eternity? Given that Japan has already answered that for us, the choice should be obvious in a logical world. Politics is rarely logical to the extent it seeks the most efficient and broad-based answer. To continue on this path is to continue to repeat historical mistakes, the primary of which was thinking that “enlightened” monetary practitioners were that.