The other day we talked about how single family housing starts suggest that the winds of change are beginning to blow. The growth in single family starts has come to a near stall. And there’s reason to believe that things could get very bad, very quickly when mortgage rates rise.

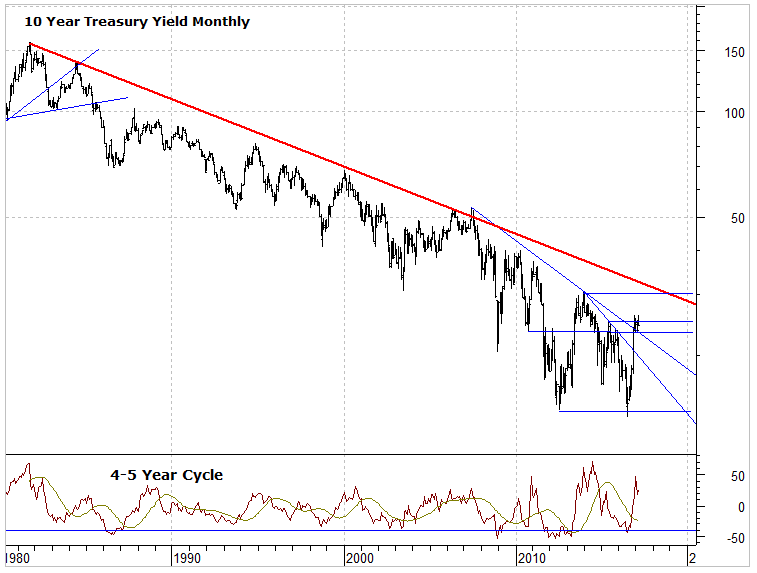

For now that rise in rates has been temporarily forestalled. Mortgage rates are tied to the yield on US Treasury notes. The yield on 10 year notes nearly broke out above the key resistance level of 2.6% last week, but they have since pulled back from the brink. The charts suggest that when that breakout happens, the 10 year Treasury yield is likely to vault to 3% in the short run. That should be enough to choke off homebuyer demand and send starts plummeting.

In the short run however, the market is likely to get a respite from the unique market dynamics. Those unique conditions result when the US debt ceiling results in a moratorium on issuance. Because government debt is now up against that wall, the Treasury can’t issue new debt. Normally the Treasury issues new debt in most months. I say most, because in months when the government collects quarterly estimated taxes from businesses and individuals, it has enough revenue to pay its bills and even pay down some debt. But in 7 or 8 months of the year the Treasury needs to borrow mass quantities, often $100 billion or more.

Dealers, banks, and investors use some of their cash flow to buy that paper. This is a built in feature of the market. But what happens when there’s no new paper to be had? The market players suddenly find a shortage of supply and a surfeit of cash. So they direct their cash to buy already outstanding government bills, notes, and bonds. That pushes long term yields and short term rates down for the duration of the debt moratorium.

While the debt ceiling is preventing the issuance of new Treasury supply, mortgage rates should move down with Treasury yields. The housing market will get a break. But this will only last until the debt ceiling is lifted and the Treasury begins issuing new debt.

While the Treasury isn’t allowed to do any new borrowing, it must still pay the bills. It does that by raiding government employee pension funds and whatever off-budget funds are available. Eventually those are depleted and then the real negotiations start in Congress. At some point there will be a deal. The current situation can only last a couple of months. Then something’s gotta give.

The last time we were under a debt moratorium, the markets rallied sharply. But once a new debt ceiling deal was done the Treasury started borrowing had over fist. When a new deal is done, the first thing the Treasury must do is to replenish all of the pension funds and other accounts it borrowed from.

At the end of the last debt ceiling crisis, on October 30, 2015 Congress and the President agreed on a suspension of the debt ceiling until March 16, 2017.

With the ceiling lifted, the Treasury immediately began to replenish the funds it had borrowed internally. From October 30 until December 3, the Treasury issued an astounding $296 billion in new debt. That supply pressure had a direct effect on the Treasury market. Bond prices plunged and yields skyrocketed. The 10 year Treasury yield soared from 2% at the end of October to 2.35% in early December.

Back then Treasuries were still in a secular bull market. Today, that proposition is questionable. A 35 basis point rise in the 10 year yield would be sufficient to break through resistance at 2.60, and possibly signal an end to the long term secular bull market. A move above 3% on the 10 year could be the beginning of a long march higher in yields.

We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it. For now we’ll look for the scenario of lower yields to play out for as many months the Treasury is not issuing new debt. In turn, we can expect a temporary respite from a meltdown in the single family development market. Any rally in homebuilder stocks or ETFs, especially one that moves back to a resistance level should provide a good short sale entry.

Multifamily starts obviously also involve land development and construction, but the multifamily market is a fundamentally different business. Buyers are not owner occupants. They are investors. They are driven by investment fundamentals, particularly rental demand.

The user/occupants of the properties are tenants. The investors who buy the properties are fundamentally interested in user demand. And that depends on tenant income dynamics. It is a complicated field of inquiry. I happen to know something about it because I spent 15 years appraising multifamily investment real estate. As with the single family market what I see today in multifamily isn’t a good harbinger for the future of this industry. Apartment REITs are likely to fare poorly.

Rents have seen a tremendous wave of inflation over the past 6 years. Over that time, rent inflation has mostly been 5-6% per year. Over the past year it has slowed to around 3-4%. Meanwhile the earnings of workers who are tenants have only been growing at about 2% per year. Tenants can’t keep up with that 8 ball. What happens? Zero growth as “The rent is too damn high!” for an ever increasing number of tenants.

In November 2015, monthly rent as a percentage of monthly worker earnings rose to a near record level. It set a new record in January 2016. Tenants were stretched to the limit. That stopped the growth of multifamily development in its tracks. But multifamily unit development continued to run at an average rate of 100 units per million people per month. Considering tenants’ ability to pay, that’s too high.

Rent inflation slowed in 2016, easing the affordability problem a bit. But industry reports show rent inflation in recent months beginning to heat up again. The problem is that the trend of more children setting up housekeeping in Mom and Dad’s basement, or vice versa, isn’t likely to change without earnings inflation beginning to catch up to rent inflation. In addition, the retirement income of retired people isn’t likely to increase in any appreciable way. So more older people are likely to be setting up housekeeping in their kids’ basements.

Likewise the trend of shacking up 2 people in a single apartment isn’t likely to go away without big increases in worker earnings. These entrenched demographic trends will work against the multifamily development business. Meanwhile it continues to produce new units at a breakneck pace. As rents inflate, the oversupply problem will lead to a bust. Or rents could drop, causing property income to fall below the level necessary to service debt. That would lead to a financial crisis and a multifamily housing bust.

As a result of these forces, both the single family builder market and the apartment REIT market look like good places to look for potential short sales.

Lee first reported in 2002 that Fed actions were driving US stock prices. He has tracked and reported on that relationship for his subscribers ever since. Try Lee’s groundbreaking reports on the Fed and the Monetary forces that drive market trends for 3 months risk free, with a full money back guarantee. Be in the know. Subscribe now, risk free!