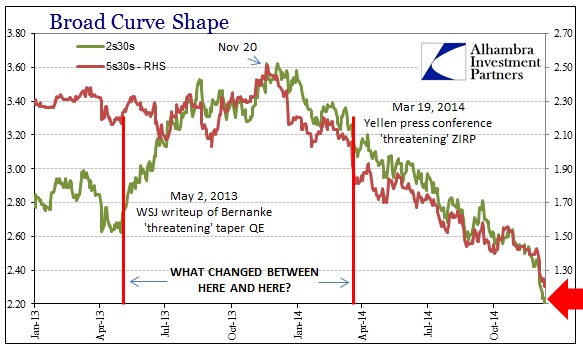

The growing sense of an economic cliff is based on three major factors, all of them in massive markets as opposed to manipulated and ill-suited statistics. The most obvious are oil prices and the UST curve (and related curve mechanics) as they have turned to prices and shapes not seen since the worst of the last crisis. The third, “dollar” balance sheet “supply”, is related to that but far harder to define.

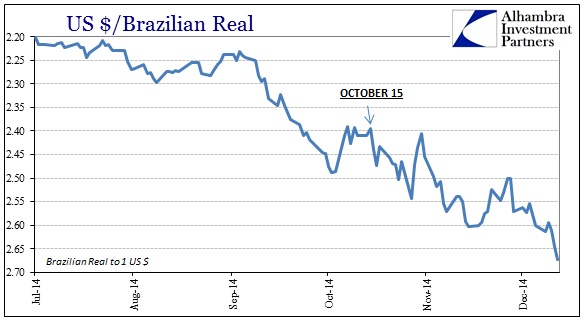

The outward appearance of dysfunction and crisis is often as a discrete event. The UST irregularities on October 15 are a perfect example, as in almost all commentary it is being treated in isolation. That is a highly dangerous mistake and it was a good start that the Office of Financial Research, an agency in the Treasury Department, was quick with a warning about making such an easy mistake. What took place on October 15 was part of a trend stretching back months, but also, more importantly, that is not yet finished.

Crises are ebbs and flows, with these obvious breakouts only showing the “tip of the iceberg.” Underneath this latest illiquidity event, repo markets had been warning of incapacity going all the way back to June (and I am convinced the ECB’s negative deposit rate was the catalyst of all of this).

In the chart above, it looks as if October 15 marked the end of the event particularly as repo fails have been back to “normal” ever since (the 8-week average is now what it was the week of June 4 when the ECB announced its NIRP decision). That would seem to suggest that treasury collateral arrangements have attained a steady state, which I think is the obvious and correct interpretation. However, the implications of that are not benign or neutral.

If we view the months prior to October 15 as a systemic withdrawal of not just evident liquidity but also capacity, then the erosion in collateral arrangements amount to a balance sheet-led “tightening.” If collateral calls were coming in during the first weeks of October, then those caught on the “wrong” side were forced to adjust and settle. That means a lot of different things, but the net effect on the other side is withdrawn risk and less extension of balance sheet positions. If you were long high yield credit, for example, and were hit with a collateral call you had to find “room” to settle that call either by shifting around other positions or selling outright. In either case, the “market”, as these are accumulations of positions that feed on themselves, has less risk extended than before.

There are downstream effects of withdrawn risk that are still playing out, though again appearing from the surface as another period of seeming stability.

Another way to express the idea of “less risk” is a reduced state of balance sheet expansion or offer; i.e., dollar supply. So where treasury collateral has settled out any obvious imbalances, that did not lead to a steady state further on in the global dollar short but rather continued ripples of “tightening.” I think the action in gold shows that perhaps as clear as anything else.

Gold prices were smashed the week after October 15 in what was an unsettling parallel to April 2013. That it would follow so closely to the after-effects of a treasury imbalance and collateral calls all across risky credit (including illiquidity in junk credit) is not surprising. Gold remains highly tied to this “dollar” framework, and thus acts as a depressive aspect of price. The real clincher, however, is the forward rate (GOFO). As the price dropped to its lowest, the forward rate turned negative and then deeply so. That would more than suggest a heavy use of physical gold as collateral (steep price drop) in the days after October 15 and then a mad scramble to replace it (gold “leasing” is “borrowing” physical to be “repurchased” at a later date).

So the first outward ripple of the treasury imbalance after-effect was into gold. Collateral strain was transmitted there in first negative price action and then the tell-tale physical shortage (which must have been quite severe for forward rates to drop as far as they did). That related to the next ripple outward, which is the current state of global currency crises.

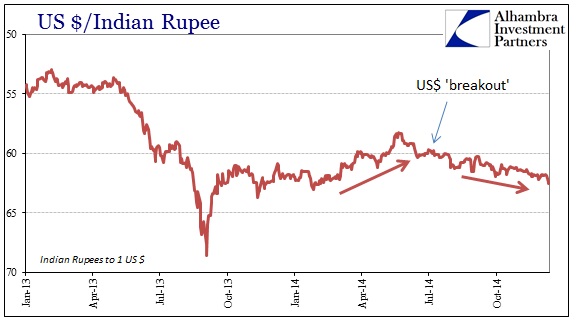

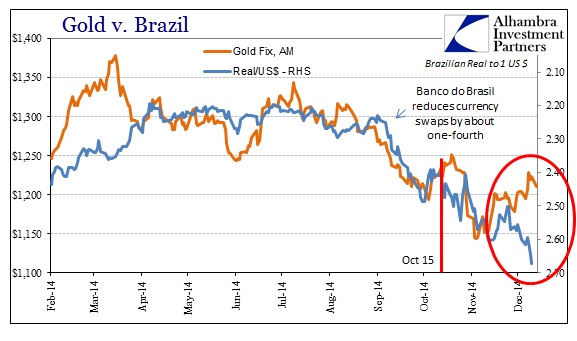

The Brazilian real has been pounded in the weeks since October 15, turning this 2014 “dollar” event worse than even 2013. While most attention has been paid to the “petrodollar” portion of the eurodollar standard, and thus the currencies of the oil producing nations, this after-effect of “dollar” tightening is far broader than that.

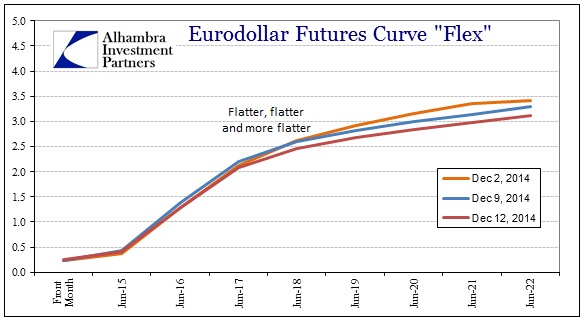

In short, continued “dollar” illiquidity that is not getting better, as the one-time October 15 narrative suggests, but rather still roiling under the surface all across the globe. The continuity of that trend is apace of oil prices and government bond curves as a decidedly dour expression of firming bearishness. “Dollar” expansion would, in all likelihood, continue unabated if global bank balance sheets were entertaining increasing risk; that they aren’t is certainly tied to policy uncertainty (as seen in the eurodollar short end) but also severe economic doubts (eurodollar flattening).

The financial and economic nexus is that credit and funding markets are entirely unconvinced there is anything like an orderly exit for the Fed (despite anything the ECB does to “offset”) and that there will certainly be economic damage from the attempt – that is what, I believe, the entire illiquidity trend has been stating going all the way back to June. And it may even be worse than that inasmuch as “dollar” relations are actually suggesting not distant economic disruption from a distant Fed exit, but rather the close relation of a much nearer global economic retrenchment.

The trade of gold in tandem with the Brazilian real, for example, has been an expression of these ripples of “dollar” illiquidity and global economic pessimism. However, in recent weeks gold has “decoupled” from the real, especially recently where credit market indications have accelerated (as has the devaluation in Brazil).

This has happened before this year as the correlation is not perfect, but not to the extent seen recently. The divergence with gold getting price support may be the beginning of the “fear trade” and gold as “tail risk” insurance, though it is far too early to tell and may ultimately reverse on collateral problems yet again.

So October 15 was not at all the end of the dollar problem but only a transition point where the tip of the iceberg showed itself if only briefly. Funding market bearishness continues both inside and outside the US no matter what the media says about that day.