There is undoubtedly serious stratification in the housing market, as higher end homes have no trouble selling at greater and greater price points. That, in turn, has left those owing homes in the tiers below struggling, supposedly, to do what Americans of past generations have done – move up to bigger and better. Because these middle level home owners are stranded, they can’t or won’t sell despite the so-called booming jobs market and leaving new prospective buyers without any options.

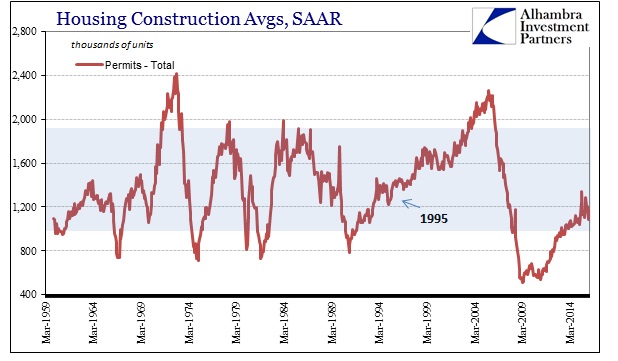

That explanation for what we find in resales leaves out what should be basic economics right at the start. If the jobs market is truly booming then those beneficiaries who should be feeling the (permanent) income effects should be causing another boom in construction. Builders would be crazy not to engage in tremendous new volume if there was all this pent up demand and steady if not steadily higher prices. Yet, housing remains stuck in the bottom of the historical ranges while apartment construction is seemingly just stuck.

U.S. housing starts fell more than expected in March and permits for future home construction hit a one-year low, suggesting some cooling in the housing market in line with signs of a sharp slowdown in economic growth in the first quarter…

Last month’s drop in groundbreaking pointed to a moderation in housing market activity and mirrors other data such as business spending, trade and retail sales that have suggested economic growth stalled in the first quarter.

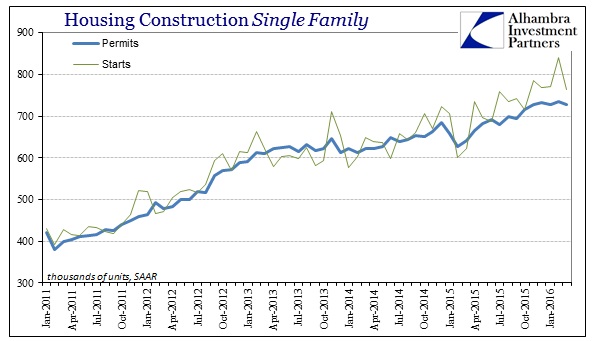

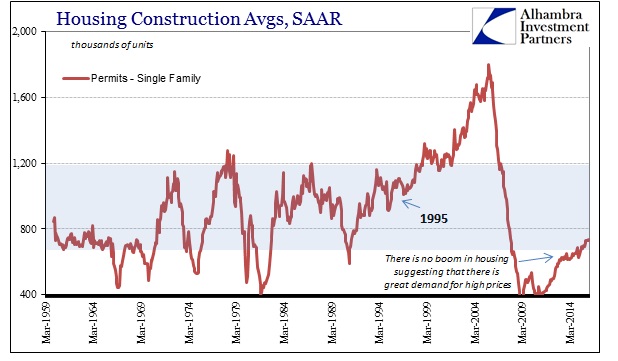

Construction for single-family homes has been relatively good, but nothing like what “should” be occurring if the economy were truly booming and there was a shortage of for-sale units. Permits for new single family construction were 727k (SAAR) in March, showing no expansion going back to last October and only modestly above the ~680k range that prevailed last summer.

Modest remains the key word in all of it. A true pre-bubble “boom” in housing used to be 1.1mm to 1.2mm units, more than 50% above the current level. So where the recent trend might still be positive, there is no indication of an overall rush of economic good fortune from those with new jobs and no place to live. It would suggest perhaps a financial problem of mortgage inequity, but that also reflects upon the true state of national income and wages of what the true labor market is likely far apart from the unemployment rate.

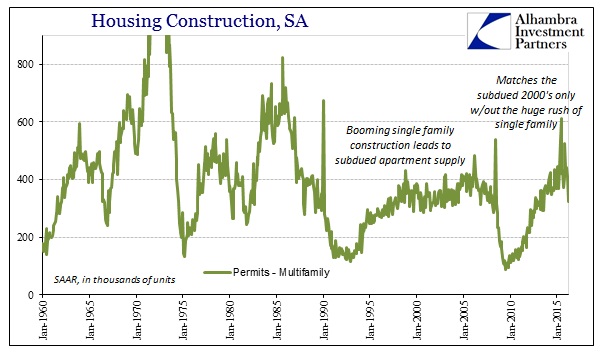

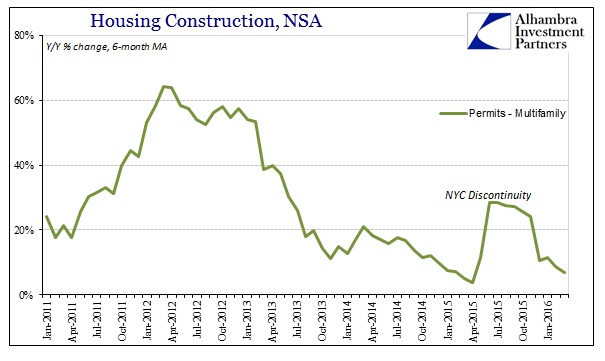

Instead, on the multi-family side, construction remains around 400k (SAAR). The level of new permits in March dropped sharply to just 324k, the lowest level since the summer of 2013. Even last year when overall construction indicated a relatively better pace it was still at the lower end of historical ranges. At about 400k, it matched the consistent apartment construction stride of the mid-2000’s which was artificially depressed by the utter insanity in single family construction. In other words, 400k is not a healthy pace in a “normal” economy but especially one that is now supposed to be “booming” in labor markets and at the same time of a persistent housing shortage as new labor entrants seek to unwind prior cohabitation arrangements.

In the multi-family segment, it seems very much as if there exists relative oversupply of apartments due to the mini-bubble injected by the Federal Reserve’s ill-suited QE interventions. Like stocks, those “investments” were undertaken with the premise of an actually booming economy in the near future where there would be sustained acceleration in demand for new housing units. Instead, we find home construction in all segments that remains rather subdued on its own terms, and quite noticeably so in relation to the supposed acceleration of recovery and growth.

Despite what should be very favorable construction economics, construction instead continues to be positive but not significantly so. As with so many other accounts, it suggests an economy that never really took off where it “should” have and that it was only the huge crash and depression up to 2010 that accounts for even these small positives. More than five years after the crash and given population expansion (+14 million in the civilian non-institutional population since the start of 2011) there is no reason that housing construction should remain so tepid save actual economic circumstances.