By Ciara Linnane & Tomi Kilgore – MarketWatch

A year ago, we explained the many ways companies make reading their quarterly earnings reports a miserable task.

We weren’t just whining. We wanted to remind companies that our readers regularly tell us they struggle to understand earnings announcements, and our job is to decode them for investors. Making that difficult isn’t helping anyone.

We noted that some of their tactics — inventing or manipulating numbers, using meaningless jargon, distributing lame executive quotes, and more — can be outright damaging, eroding investor trust and creating skepticism.

We hoped they’d change their ways.

We’re sorry to say that today, as another earnings season draws to a close, things are even worse.

“Companies are definitely less transparent than they used to be,” said Leigh Drogen, founder and chief executive of Estimize, which crowdsources earnings estimates. They are “using accounting schemes that are more specific to … how they want investors to perceive their results.”

Earnings are a crucial quarterly update for investors, as they provide the “best unbiased” view of what’s going on with companies, sectors and the economy, said Karyn Cavanaugh, senior market strategist at Voya Investment Management. “Earnings discount all the noise,” she said.

But today, according to FactSet, more than 90% of S&P 500 companies use their own metrics in an attempt to make their numbers look better. Some conceal revenue and other key numbers in hard-to-access tables. And a recent NYSE rule change has led some companies to report very early in the morning and pushed others to join the posse reporting after the closing bell, creating bottlenecks.

While all this has meant more stress for reporters and analysts, it’s also made things harder for everyday investors trying to do due diligence on the companies they own. Experts say more companies seem to be breaking the most fundamental pact they have with their co-owners: to keep them informed of the true state of their business.

“It’s a holographic presentation bubble distorting underlying operational reality,” said analyst Nicholas Heymann at William Blair. “Companies are working all the angles.”

Mind the GAAP

The growing use of non-GAAP metrics — those that don’t comply with U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles — was one major, and growing, headache we saw this earnings season.

Companies are obliged to present their earnings using GAAP, but are allowed to use non-GAAP measures to supplement the information. Executives typically claim that non-GAAP numbers are a truer picture of their underlying business because they strip out one-time items such as litigation or merger-related charges or the write-down of assets that have lost value.

Under SEC rules, they are obliged to give equal prominence to GAAP and non-GAAP numbers, and must fully explain how they differ.

But companies often use adjustments described in terms that make them sound very similar to GAAP measures, making it difficult for investors to determine a company’s true financial performance; they don’t calculate non-GAAP measures uniformly, creating further confusion; and because non-GAAP numbers are not subject to audit, they are not checked for comparability, consistency, compliance or accountability.

“There isn’t much scrutiny that’s given to those numbers,” said BTIG analyst Brandon Ross. “There’s no government standard.”

“I am particularly troubled by the extent and nature of the adjustments to arrive at alternative financial measures of profitability, as compared to net income, and alternative measures of cash generation, as compared to the measures of liquidity or cash generation,” Securities and Exchange Commission Chief Accountant James Schnurr said in a recent speech.

How much does this matter? Data show that the spread between GAAP earnings per share and non-GAAP earnings per share has widened significantly for industrial companies in just a few years. Non-GAAP EPS was higher than GAAP EPS by an average of 25% in 2015, compared with just 6% in 2013, according to William Blair’s Heymann.

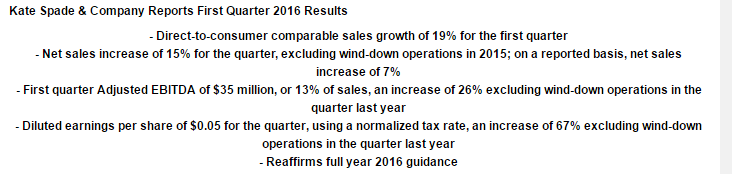

Companies don’t just use non-GAAP figures: They trumpet them. Some put a dizzying array of non-GAAP numbers right at the top of their news release, as Kate Spade KATE, -1.03% did this quarter:

And companies use so many different profit numbers — operating profit, profit from continuing operations, continuing earnings minus currency effects, income from continuing operations attributable to noncontrolling interest — that, as a whole, they can be borderline incomprehensible.

Billionaire Warren Buffett, viewed by many as the most successful investor in history, ranted in his latest letter to shareholders about how the reported earnings of some companies can be a “charade” and “phony,” particularly as companies try to “non-GAAP”-away the real costs of doing business.

“If real and recurring expenses don’t belong in the calculation of earnings, where in the world do they belong?” Buffett asked.

Non-GAAP disclosures have caught the attention of regulators. SEC Chairwoman Mary Jo White and SEC Commissioner Kara Stein, among others, have wondered whether there is sufficient oversight of how companies report earnings.

The media, too, has been criticized for reporting non-GAAP measures without referencing the GAAP numbers or identifying the adjustments.

Apple Inc. AAPL, +0.32% which has typically produced a clean report, joined the fray this earnings season, highlighting a non-GAAP adjustment to its services revenue in supplemental information posted to its website.

This was only the second quarter Apple has presented a non-GAAP metric, according to research firm Audit Analytics; it hadn’t done so since 2009. Apple did not respond to a request for comment on its use of a non-GAAP metric.

Experts agree that non-GAAP disclosures that shed light on underlying business trends are useful.

“The point of non-GAAP is generally to give a better understanding of that longer-term trajectory versus something that could have been a one-time issue that won’t have an impact on the future,” said Drogen from Estimize.

But, he, too agrees the system is too open to abuse.

Wait — where’s the news release?

Another pain point: The growing number of companies that no longer put their earnings into a tidy news release, instead distributing a link to their website, which links to a “shareholder letter” that is often a confusion of tables and charts.

Netflix Inc. NFLX, +0.46% is known for irking reporters and analysts, who must click away even as the site slows due to increased traffic, in this fashion. This season, it was joined by blue-chip General Electric Co. GE, -1.53% which linked to a release full of numbers it deemed important, but that might not be understood by investors who aren’t privy to measures followed by insiders.

At the top of its release, GE highlighted first-quarter GAAP EPS from continuing operations of 2 cents, but the real bottom line — a loss of 1 cent a share — wasn’t visible until the financial table on page 5.

The number best compared with analysts’ expectations, “GE industrial operating + verticals EPS” of $0.21 per share — which FactSet used for its comparison — wasn’t listed as non-GAAP, adjusted, core or even pro forma EPS, terms investors have learned to recognize.

A GE spokesperson explained that the shedding of GE Capital assets — $166 billion of asset sales signed as of the end of March — was such a transformative move that it required a unique way of reporting the performance of the businesses it was keeping.

Companies say publishing material on their own sites lets them offer detailed and robust disclosures, including charts and graphics, that a text-only format wouldn’t allow. And some analysts have said they don’t mind clicking through to other sites, or reading “supplemental” tables filed with the SEC to provide numbers excluded from the original release.

“We always appreciate companies that are transparent, and give us as much information as possible, to help us do our job,” BTIG’s Ross said. “But sometimes, it’s more about the presentation than about the quality of earnings.”

Some analysts say that rather than earnings per share, which can be manipulated by such things as share repurchases and investment income, revenue would be a cleaner metric for investors to follow, because actual sales can’t be masked. But some companies make even figuring that out difficult.

Large oil companies, which have seen revenues tumble with oil prices over the last year, prefer to highlight other metrics, such as capital and exploration expenditures, cost cuts and production capacity.

Chevron Corp. CVX, -1.30% reported sales in the second paragraph of its earnings news release. But Exxon Mobil Corp.’s XOM, -1.19% first mention of revenue is in the financial table, marked as “Attachment 1,” below all the company’s disclosures.

“Exxon Mobil communicates its quarterly earnings in a way that meets or exceeds regulatory requirements,” a company spokesperson told MarketWatch via email.

Early birds

Another trend that may be making it more difficult for investors to gauge a company’s earnings is a shift toward earlier reporting, which makes it harder for some investors — particularly those on the West Coast — to review and trade on the results.

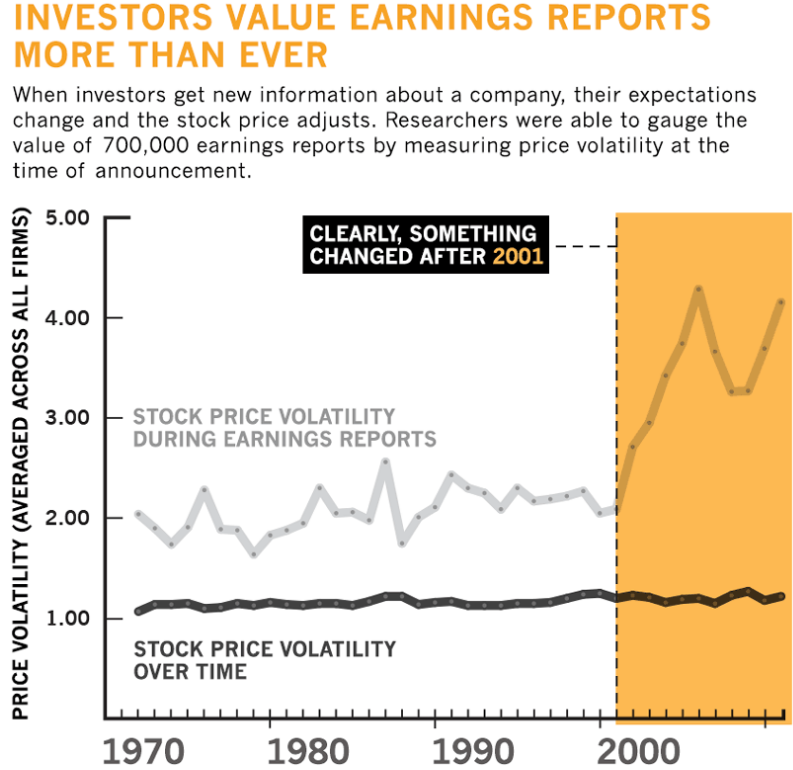

The earlier the release, the fewer people there are trading and therefore, meaning less liquidity for traders. Studies show that market liquidity during earnings reports has become increasingly important, as this chart from a recent Stanford Business Graduate School study illustrates:

A NYSE rule on disclosures, amended in September, says that if a company releases news of “a material event or a statement dealing with a rumor,” between 7 a.m. and 4 p.m. Eastern, it must notify the exchange by “telephone” at least 10 minutes before the announcement is made. The rule was adopted to match a similar rule used by the Nasdaq.

Some companies have shifted their reporting times to avoid that requirement. Xerox Corp. XRX, -2.00% spokesman Sean Collins said the fact that the company now releases results at 6:45 a.m. Eastern is related to that rule.

And Johnson & Johnson JNJ, -0.53% now releases results at 6:40 a.m., rather than at 7:45 a.m. as it did in the past. The company said analysts had been requesting earlier releases, to give them more time to study the results before the usual 8:30 a.m. time for its conference call; the NYSE’s new rule helped push it to do so.

What’s to be done?

As the use of these practices has expanded, the ones we wrote about last year — such as listing last year’s results in tables before this year’s, rather than the other way around as is customary; burying important information in piles of paragraphs or videos that should be written clearly; and leaving key calculations for readers to do themselves — have stuck around.

Experts agree that earnings season would be easier to navigate if companies were obliged to conform with some kind of template that presented numbers in a standard way. At present, the SEC has no recommendations, outside of GAAP and non-GAAP reconciliation and rules for the timing of filings.

The SEC’s White told a Silicon Valley audience in March that the regulator is questioning whether the use of non-GAAP measures has “gone overboard.” Non-GAAP metrics are especially common among tech startups, that may not yet have income or revenue and rely on other measures to show their business is moving forward.

“It’s something we’re looking at as to whether we need to actually rein that in a bit, even by regulation,” she said.

Accounting experts say there are already enough examples of companies stretching the rules to make regulatory intervention almost inevitable.

”Given all the saber-rattling by the SEC over the deficiencies in earnings releases these days, I’m surprised that some companies continue to be careless in this area,” said Broc Romanek, editor of TheCorporateCounsel.net.

Others agree it’s time for change.

“It’s about time this conversation took place,” said Drogen, who lamented that the rules are looser in the U.S. than in some emerging markets. He would like companies to be obliged to meet their quarterly filing requirements with the SEC at the same time as they publish their earnings news release, ensuring that all the information is immediately available to all parties.

“This is the way it’s done in other countries — even China, for God’s sake, and their market is the wild west,” he said. “It’s ridiculous.”

Source: Here’s How Investors are Duped Each earnings Season – MarketWatch