I was rather content to let the matter lie after devoting a couple of lengthy expositions to it, but the Fed has its own way of confirming every charge. I am writing again about the fact that the assumed monetary agency was quite curious about the dramatic changes in banking and money at one point in the not-so-distant past only to be fixated not long after with only avoiding it. It would have been hard not to notice the eurodollar’s first appearance on the global financial stage given that it replaced the gold exchange standard under Bretton Woods. However, it was safely tucked by monetary orthodoxy into the box of benignity and the Fed went on the rest of the 1980’s and into the 1990’s confident about all sorts of economic and financial control.

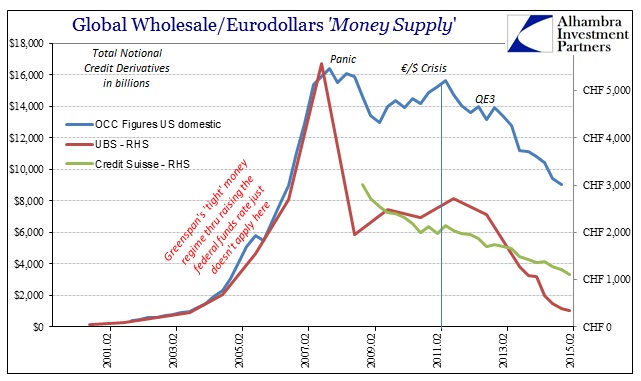

There were numerous reasons to think all that misplaced even as the 1980’s continued on, but by the middle 1990’s it had become undeniable – though still nothing was done about it. I continue to refer to Greenspan’s “irrational exuberance” speech, which is very well-known and persists in lore and legend, because it was actually about his mystification over “some” monetary shift. Given that his thinking within that speech transferred toward asset bubbles with regard to such a question, I cannot fathom as to why the Fed chair or anyone else associated with the FOMC would not revisit the eurodollar notion that was once rather contentious and upfront.

That was the essence of what I have called the Fed’s 1979 warning; that monetary character and banking itself was changing and in ways that were worried not, ultimately, predictable. And by 1996, Alan Greenspan was in high disregard for how money suddenly wasn’t acting predictably (specifically, that economic and money correlations weren’t holding). As if to extend that line from 1979 through 1996 all the way to 2015, sewing up 2008 along with it, San Francisco Fed President John Williams expressed Friday the same wonderment with apparently decreasing understanding. In other words, the Fed knew somewhat of eurodollars in 1979 and has been growing only more ignorant as time has passed:

“I see this as more of a warning, a red flag that there’s something going on here that isn’t in the models, that we maybe don’t understand as well as we think, and we should dig down deep deeper and try to figure this out better,” he said during a panel discussion at the Brookings Institute in Washington.

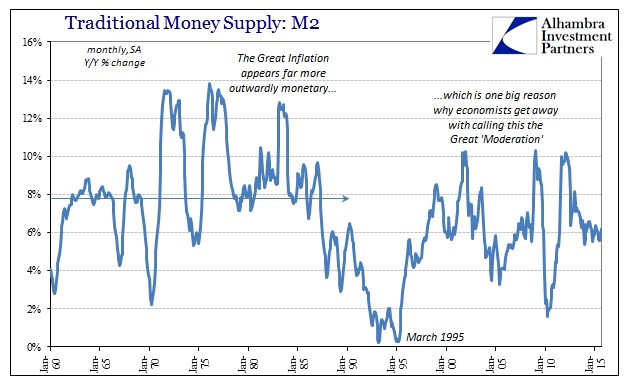

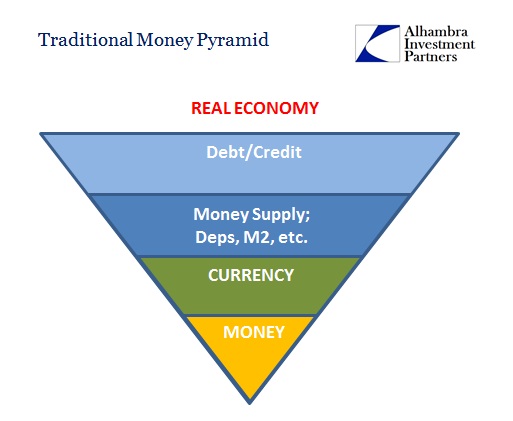

He was speaking about “low neutral interest rates” which is nothing more than orthodox econometrics for an economy that doesn’t respond to the Fed’s prodding. These economists assume that the fault lies in the economy itself (secular stagnation or natural rate theory) rather than in their monetary thinking which still finds some kind of traditional “pyramid” structure; even though the great “clue” about how that no longer applies can be found in how M2 never found the great and biblical housing bubble.

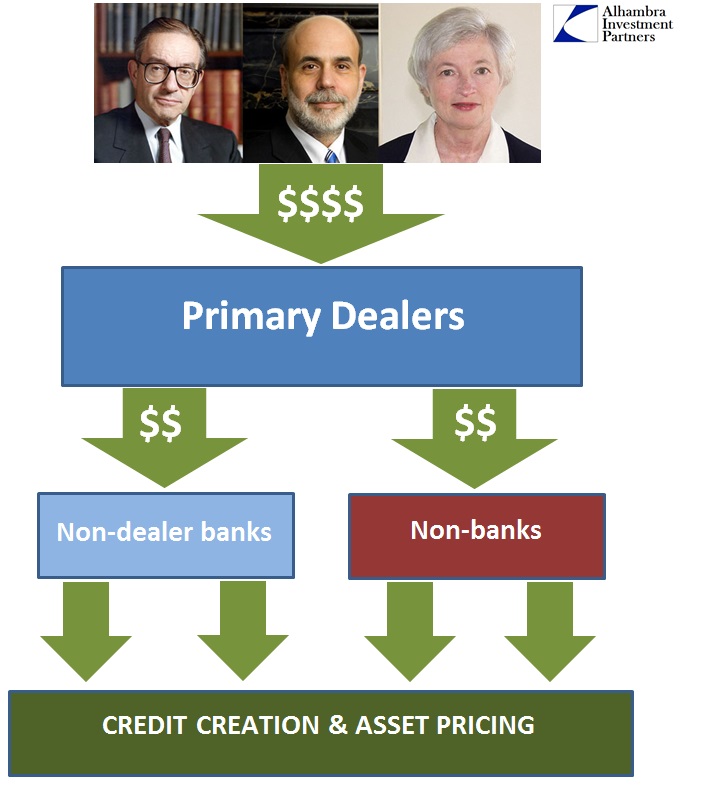

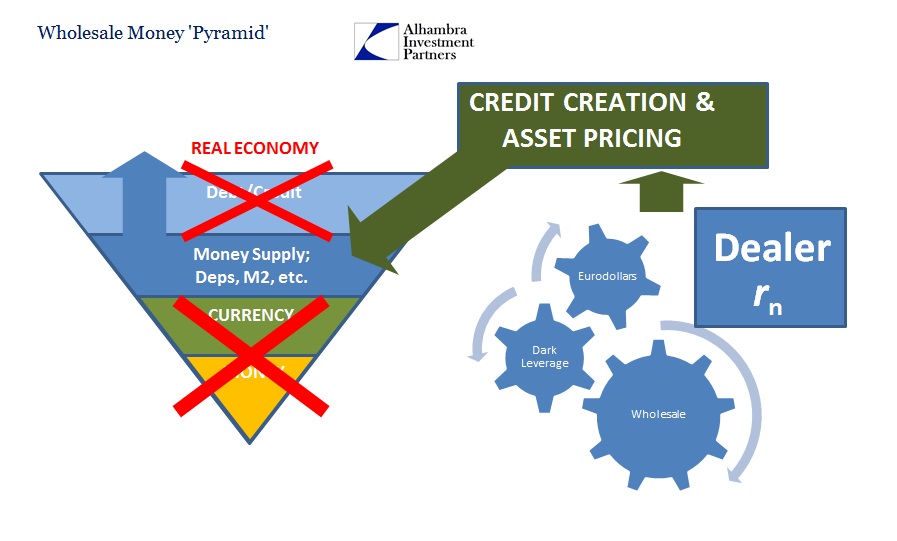

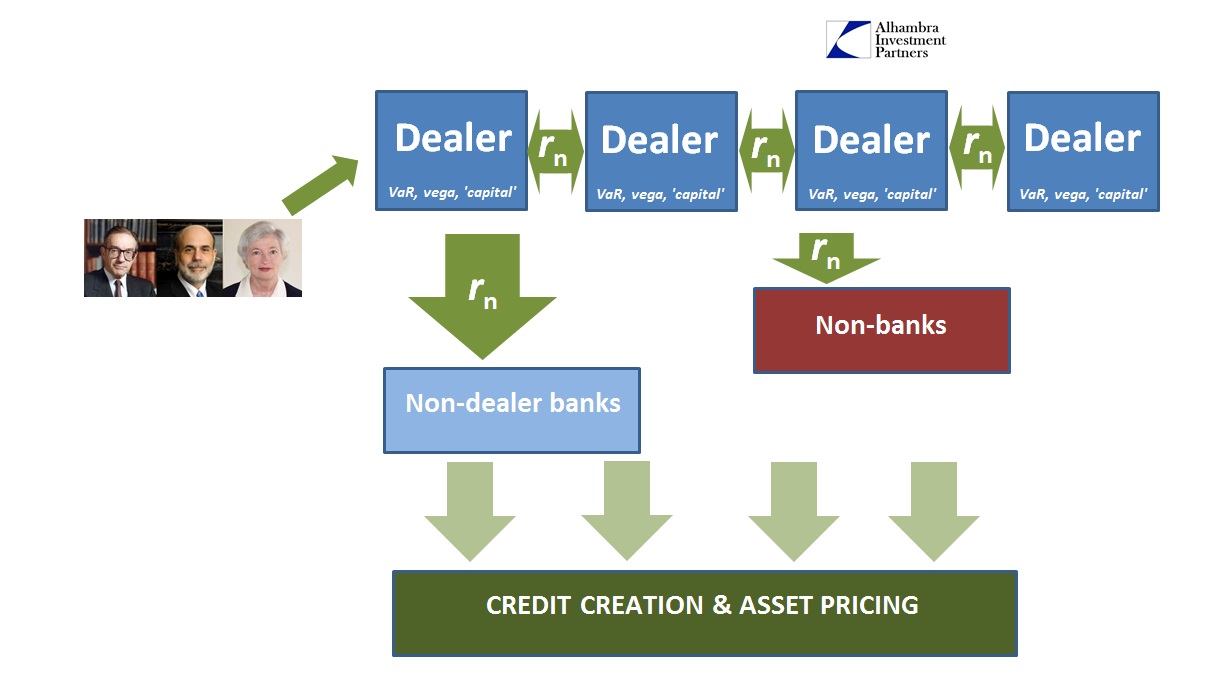

The assume hierarchy of the orthodox foundation stands as John Exter’s inverted pyramid, only with gold and hard money no longer at its founding apex. In less-restrained envisioning, the Fed sits at the top ready to change the quantity and “cost” of reserves, which then is supposed to act on “money supply” including deposit quantities, all leading to regular and direct conditioning of the economy (excluding, notably, asset prices and the full measure of credit creation because orthodox economists take no responsibility for anything outside Fisher’s quantity theory of money).

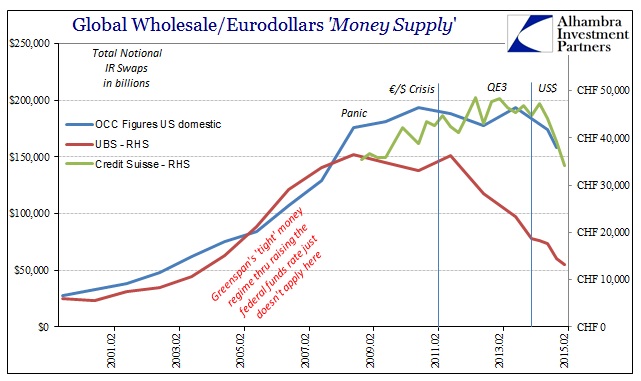

Dating all the way back to at least Greenspan’s irrational exuberance, that relationship clearly shifted as wholesale eurodollars replaced a great deal of the traditional mechanics (which is why it has been referred to as “shadow” banking; not because banks were hiding it but rather economists refused to look for it). Bank balance sheet factors and math supplanted even currency as the basis for the construction, in no more easy and straightforward pyramid structure. It is that amorphous conglomeration that holds a great deal of difficultly with not just policy but even figuring out which is where and why.

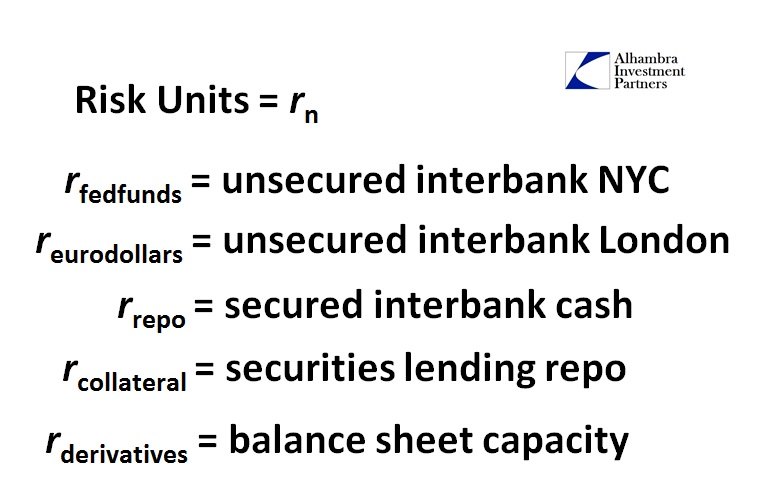

In this structure (which, in reality, is far more complicated than what I have represented above) money and currency are but menu options upon a range of wholesale liabilities, each their own versions of money-like behavior. In this manner, the eurodollar (which actually encompasses other wholesale elements, even federal funds) has totally re-arranged the format of traditional money factors. Credit and asset prices are no longer tied strictly to traditional ideas of money supply, especially deposit balances. Instead, the wholesale model has replaced the pyramid as credit creation is a direct output of eurodollar and wholesale existence; that has the effect of, in our conception here, pulling credit and debt production out of step and placing deposits (the M’s) now after.

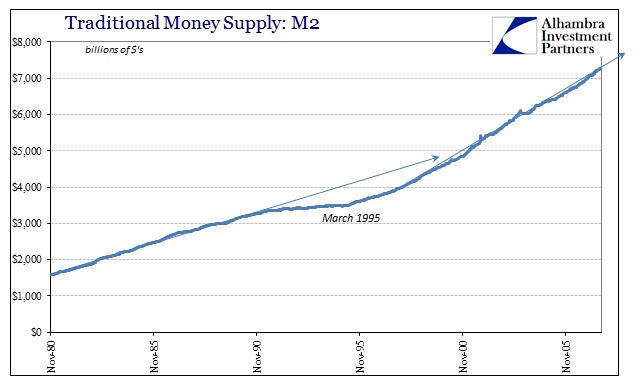

Thus, as noted in my last post on this topic, deposit balances (traditional money supply) don’t show any of the asset bubbles but rather just the byproduct of wholesale credit creation and the vast financialism that accompanied it. In that regard, credit default swaps were far, far more of relevant “money” than anything the Fed believed then and, apparently, now.

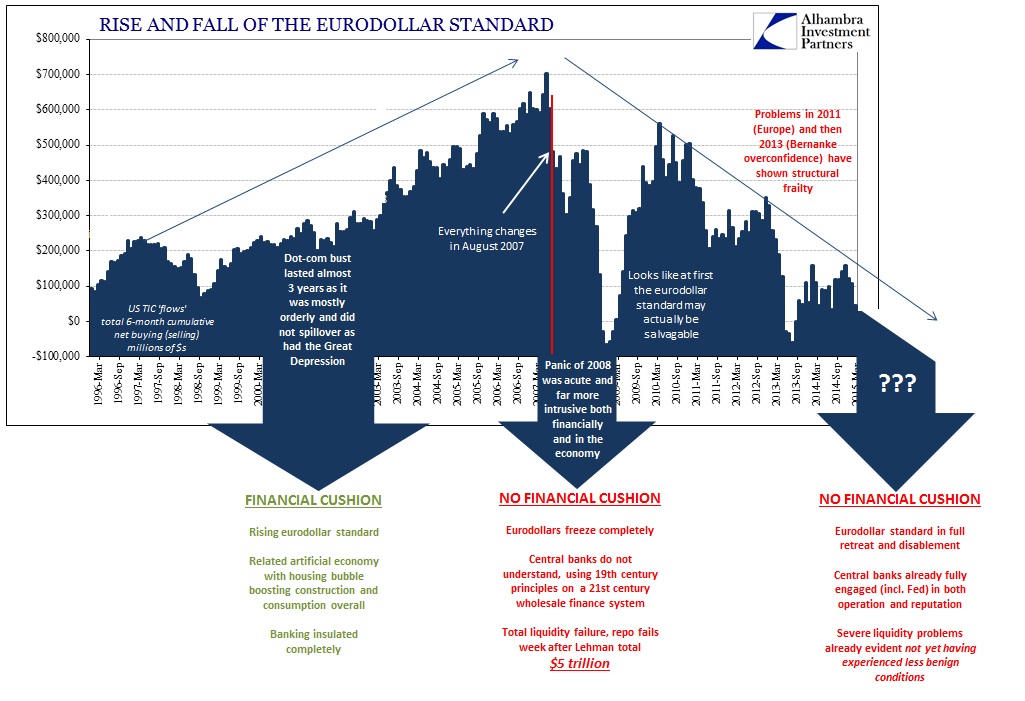

John Williams’ confusion over a “low neutral interest rate” is really just restating the Fed’s impotence in this highly-altered wholesale arrangement. Bank balance sheets are under extreme and unending pressure, which has the very practical effect of “clogging monetary transmission.” Like it or not, the Fed is finally coming face-to-face with the eurodollar’s decay even after taking (unexpectedly) an acute and almost fatal dose of it starting August 9, 2007; though coming to terms with the eurodollar is also a highly relative statement, as it consists of these economists planning to run some regressions to see if how they can instead retain their worldview.

The institution was keenly aware of the eurodollar throughout the 1970’s (far more than just that 1979 warning) but now it’s as if they have never heard the word before. That the entire global banking and monetary arrangement was altered by it long ago makes such a position beyond negligent. It is, however, instructive that the head of one of the major Fed branches comes right out and says that they really don’t know what they are doing. Figuring out why is but a slight jog back in history.