The face of economics as it currently stands is the central bank. We have been programmed to simply infer that status in almost everything (good) that happens in the economy. In many ways, there are traces of that in the first concepts of central banking, even going back to the reformation in the latter half of the nineteenth century. For its part, the Federal Reserve at its creation intoned those basic principles: good liquidity leads to good banking which leads to good economy.

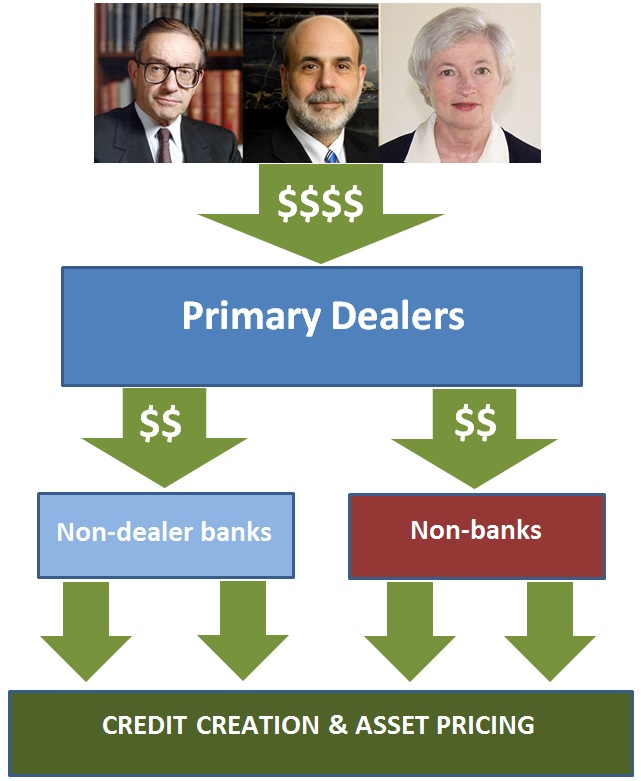

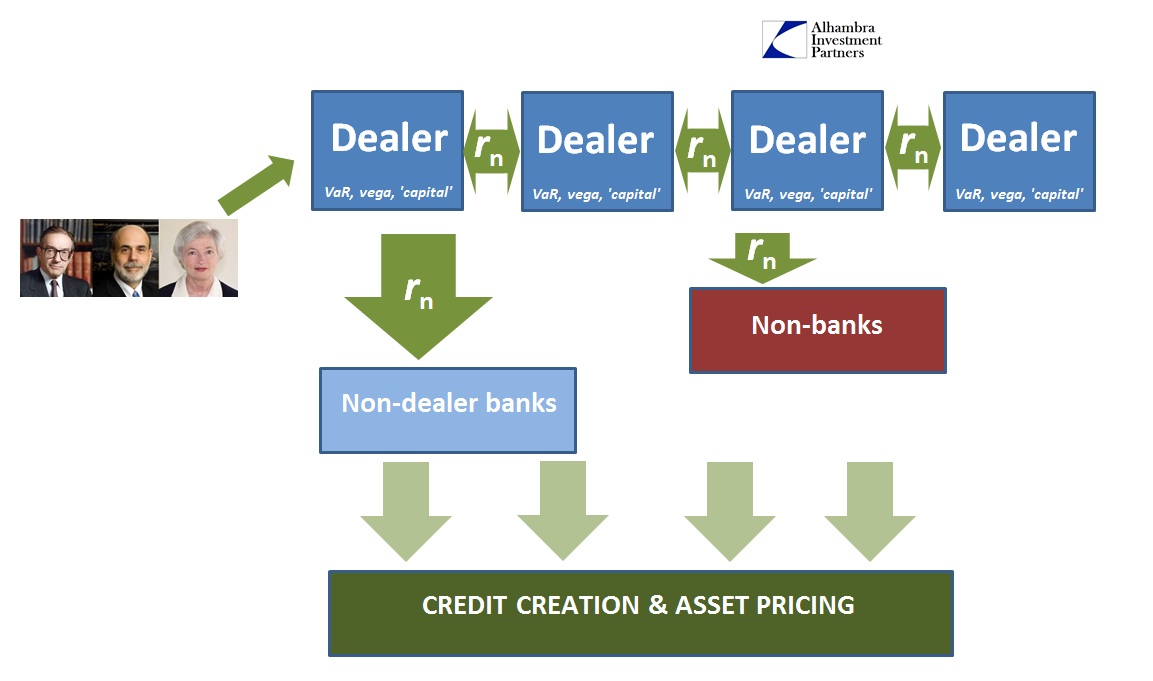

Even a century later that formulation still, somehow, holds for the majority. Economists will talk about central bank policy needing to be “loose” or “tight” as if it were as easy as that: looser policy equals good liquidity which leads to good banking which leads to good economy. And so the framework is presented largely as:

It was never that simple, as even the Great Depression should have impressed, but as long as that idea held at the wider margins it was taken as a fact of financial existence. In other words, it appeared to work that way for long enough to simply assume that was that.

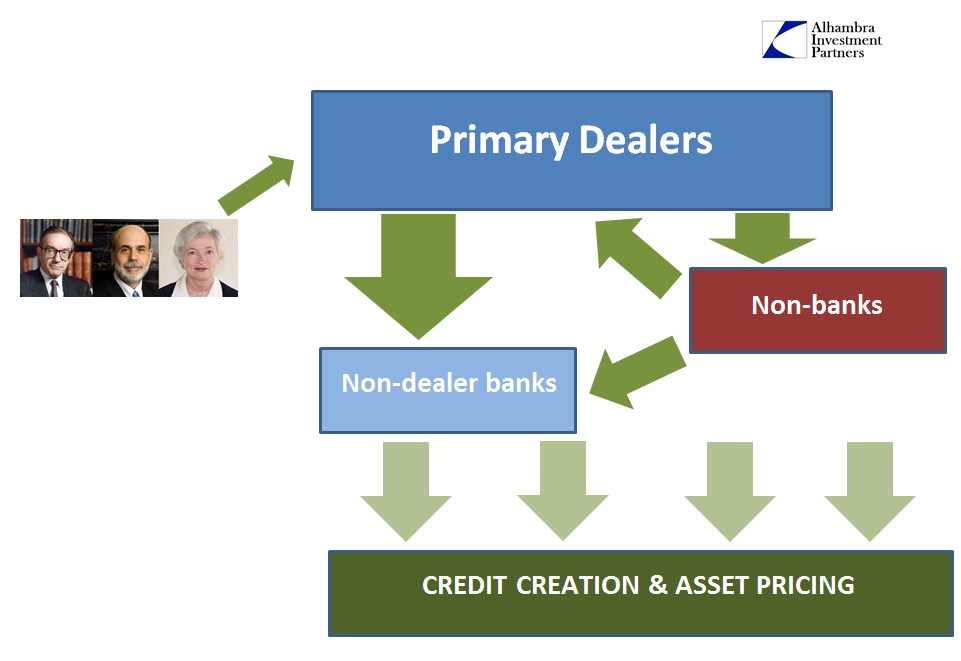

Yet, for all that simplicity, the evolution of banking made it all obsolete. As I noted before in Basic Interbank Math, there is not just some small room between “liquidity” and “reserves” there is a world of difference. In observing that fact the entire financial system needs to be re-ordered whereby the central bank not only plays a smaller role but actually one that is tangential and indirect.

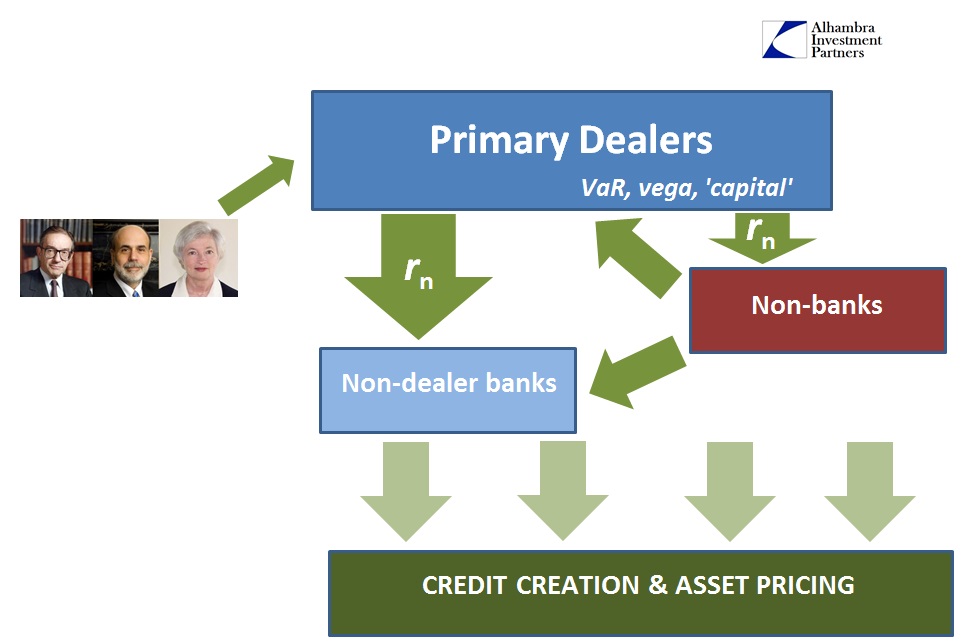

Under this kind of schematic, the behavior and activities of the dealers are the primary essence of finance; policy projection or not. If the Fed cannot influence the dealers it cannot influence anything, a curt and general description of August 2007 forward. A good part of that is due to the geographical divide of the heterogeneous “dollar” system, spread between domestic “dollars” in NYC and eurodollars centered largely in London. Again, dealers play the central role this time in both, with the FOMC and Open Market Desk largely irrelevant until open-ended dollar swaps with foreign central banks (thus too big to fail is literal in maintaining order; which is not to say whether order in this system is preferable to disorder into something that might replace this setup).

The limitations governing the role of dealers is where Basic Interbank Math focused, mainly in the general conception that balance sheet mechanics govern “liquidity” as very much distinct from any policy intentions. Thus the quantity of “reserves” created by the Fed is only an indication of what the Fed wishes the dealer network to accomplish without any direct influence over whether they might. Instead, dealers are subject to “capital” and risk calculations that govern their actions. To that extent, the change in FAS 157 in March 2009 was the greatest influence on balance sheet mechanics as it withdrew mark-to-market pressures from reducing balance sheet capacity (I am not making a value judgment on the appropriateness of the action, only observing that it was by far the most efficacious “monetary” policy available for the very reason that balance sheets, and thus systemic liquidity, were contracting due to marked losses eroding “capital”).

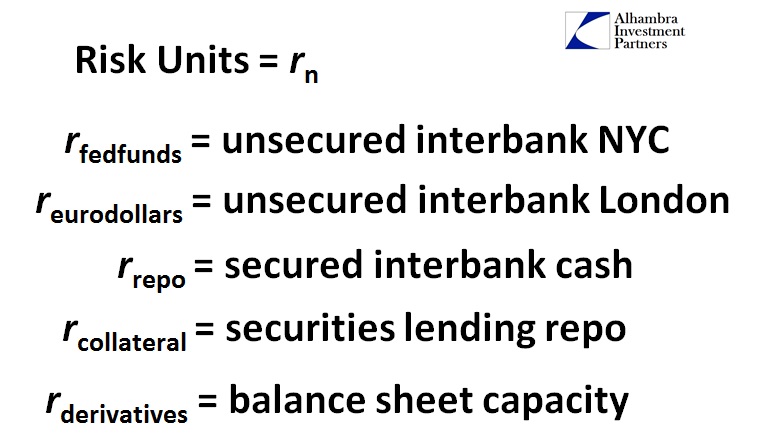

So liquidity as a systemic reality in this wholesale system takes on a complexity that is misunderstood, well beyond the simple idea of “money supply.” In the idea of balance sheet mechanics, the willingness and ability to provide “money like” activities is due to the very complex interactions of all the various parts of dealer finance. That is perhaps the illumination from the panic in 2008 that stands out the most, in that, at times, there were other facets of this modern plumbing that behaved more like currency than currency. The most obvious and understandable aspect was repo collateral, which in the context of the panic showed that true elasticity wasn’t “cash” it was usable collateral at a stable haircut – something the Fed wasn’t setup to provide on a sufficient scale (though it did try in minor programs, notably some weeks after Bear Stearns failed and then again after Lehman failed; notice the tendency toward “after”).

It isn’t just repo collateral that is “money like”, as even the various risk governance factors on balance sheet capacity can be traded and used every bit as “liquidity.”

To use a pre-crisis example, the rise of credit default swaps in the late 1990’s and especially the mid-2000’s was not one of pure speculation as it has been drawn in the conventional imagination. The point of credit default swaps was one of risk management, as in the case of hedging huge credit positions. A financial firm wanting to take on an MBS tranche tied their ability to do so to the amount of “risk” they could lay off in the form of a derivative trade, in this case CDS.

That meant, in terms of market behavior, the ability of the “market” to absorb new credit issues and maintain pricing was tied directly this risk absorption capacity of the dealer network. As long as the dealers were willing and able to take on risk by writing CDS protection, the overall systemic capacity to increase credit production was preserved, and indeed greatly enhanced.

The behavior of derivatives dealers in the bubble period, which included monoline insurers and even ostensibly insurance companies like AIG, tended toward over-speculation simply because the risks appeared (read: calculated) minimal in having to meet contractual obligations of writing protection. And that was due to the Fed’s implicit “put” under asset prices, something that was totally self-fulfilling. Thus monetary policy could project to the dealer system in this case as a balance sheet expansion due to low assumed volatility – a central point at the heart of all of these calculations.

But it wasn’t monetary policy directly providing “stimulus” as it was the dealers taking that cue and mathematically expressing it in their risk management regimes. Thus, they were only too happy to provide and trade balance sheet capacity, in the form of writing CDS, to the wider credit markets which allowed non-dealer financial participants to take on more credit positions at cheaper prices. The fact of risk absorption meant the whole of the credit system could expand rapidly and would not have without it. In that way, the ability to increase balance sheet capacity was like finding massive new gold fields under a gold standard.

The part of “liquidity” being transmitted from dealers was not limited to currency or eurodollars, but something like “risk units” which encompasses the full range of financial operations. The amount of “risk units” dealers can provide to the wider system is governed, again, by balance sheet calculations of “capital”, VaR and bottom-up accumulations of all the various portfolio vegas (which is why banks will offset the activities of different trading desks against each other even though they are not related in any other way). Which form these “risk units” take is derived from “market” demand and utterly complex calculations of counter-factors, feedbacks and, as it should be, profitability.

The “block” of dealers is not homogenous, however, as each has its own characteristics and portfolio constraints that add unique properties to the whole. Furthermore, dealers themselves provide “risk units” to other dealers, especially in derivatives markets. While that could theoretically act as a potential stabilizer should one dealer stumble, past experience suggests otherwise as reduction in tradable balance sheet capacity in one, meaning fragmentation, has been deleterious and amplified toward total and cumulative “risk units” available to the whole.

In short, “money printing” in the modern age is unbelievably complex, touching a whole range of financial factors that have very little to do with the quantity of inert bank “reserves” created by the Federal Reserve, ECB or anyone else. The ability to nurture and maintain credit expansion and pricing is not easily observed, in fact all but impossible directly, made so by this tangled web of modern financial modeling and conceptions.