The problem with the employment report is not just about how it is calculated but more so that it is taken as the definitive measure of economic performance. The notion itself, conceptually at least, isn’t assaultive as the modern economy is entirely about the division of labor and specialization, so anything that deals in that subject matter is already in the right place. This particular brand of economic account, however, isn’t so definitive as to have earned such blind faith, especially during this “cycle.”

As it is, the Establishment Survey and unemployment rate are lagging indications, not forward-looking. The unemployment rate, at its best, may be able to say something about what just happened but is far less intuitive about what will happen. That point really gets lost in the shuffle, especially from the “establishment” that is clinging to anything that might suggest there will never be any economic refutation to monetary “magic.”

March’s bad jobs numbers plus a slew of other bad economic data — which combined for a pathetically slow GDP growth number for the first three months of the year — had some worried that the reasonably strong jobs and overall growth of 2014 had come to a halt. The good news is that March, and the first quarter, may have been a bit of a blip — today’s report also indicated that February’s numbers were even stronger than expected, adding 266,000 jobs.

That’s some sure selective reading about the economy, not the least of which is the internals of the payroll report itself. The economy has “come to a halt” in terms of both big and small; the big being in late 2007 as the level of actual and beneficial employment since then has shrunk in even absolute terms, and in relative terms it is something of a depression. In the “small”, there is the matter of the “dollar.”

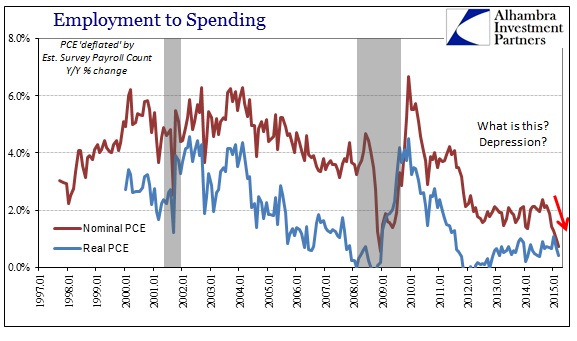

Just as the economy, via the Establishment Survey, was taking off, the rest of it did the opposite. That much is clear from the spending figures all over the place, from PCE to retail sales, that show this sinking nature is much more the baseline and anything high and “great” the deviation.

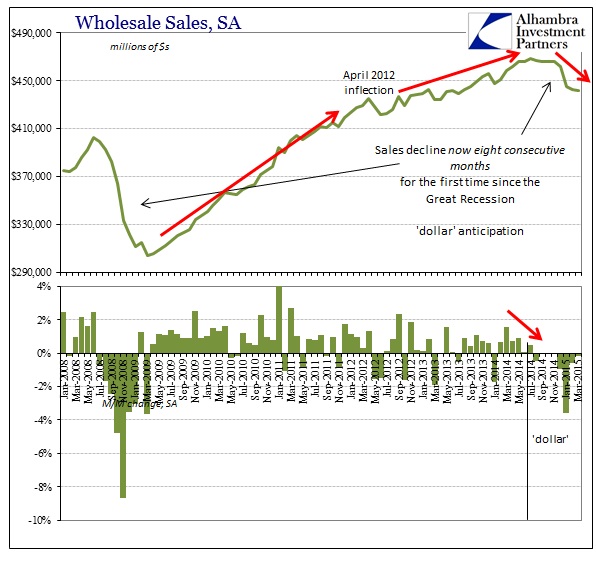

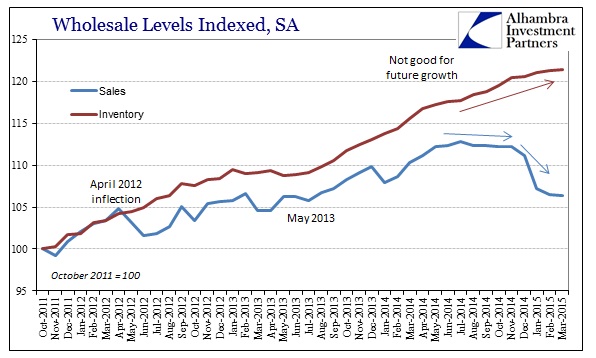

It is not consistent with a booming economy, recovery or anything else that the count of employment should so rapidly increase but nothing else does in association. Not only is household spending declining at the retail level, wholesale sales continue to fall off too. And we have yet to see inventory turn lower with sales, meaning the twin (potential) disaster of overcapacity and overproduction simultaneously.

The latest estimates from the Commerce Department show that wholesale sales for March were down again by 1.3% year-over-year. In seasonally-adjusted terms, sales have declined now for eight consecutive months.

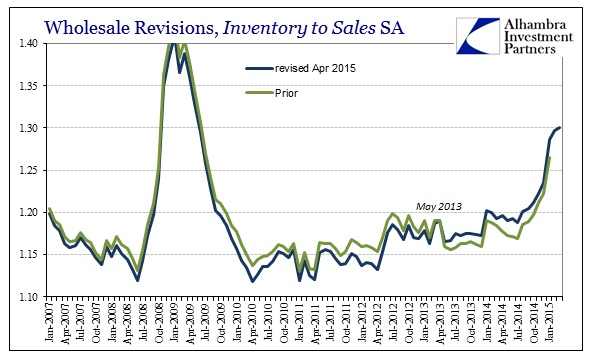

Balanced against those declines is inventory still rising. Y/Y in the unadjusted set, wholesale inventories were up again, this month by 4.9%. That has left inventories split from sales to a degree not seen since the worst days of the Great Recession. You can make the argument that conditions now are far better than those, and that businesses will hold on to high levels of inventory in anticipation of the turnaround everyone has been talking up incessantly, but businesses have been told that story before (notably just last year) to no avail and the particular conventions of business have not been repealed as monetary faithholders would have everyone believe. Inventory is inventory, and it must be dealt with when it gains these kinds of extremes.

While sales have tailed off, there is no sign of that in the inventory part. The common defensive instinct is to write that off as a matter purely of petroleum, but the fact is that non-petroleum inventories have gotten way out of hand in relation to non-petroleum sales; and they have done so in coincidence to all this great job creation.

In seasonally-adjusted terms, wholesale sales ex petroleum are down 3% since so far in 2015, showing no net growth since July of last year. Again, that is the same period as when the Establishment Survey shows the greatest gains since the late 1990’s. The incongruence is astounding, yet for all economic commentary it is the raw job count of the highly adjusted BLS figures that stands in for what might actually be happening; and then worse, those same, dubious “payroll” figures are used for forecasting where the economy is going next.

From that, you can begin to see why the recovery economists are so sure is right around the corner never is. What we can reasonably assume here is that the economy was bumped in a manner not seen since the Great Recession, and that we still don’t know how that will be resolved. The inventory problem is enormous and it at least suggests far more humility about assured rebounds that have never yet arrived and to which are based on arguable figures that at best are backward facing.