This week the Fed will add $35.7 billion in cash to Primary Dealer Trading Accounts. How can that be, you ask? The Fed ended QE in early 2015. It has kept the total of the assets it holds flat at about $4.5 trillion since then. The Fed isn’t pumping cash into the market… Or is it?

This is one of those, “It was a dark and stormy night” stories. In other words, it’s a bit circular. I’ll do my best to straighten it out for you, and tell you what it means for the stock market.

Under QE (Quantitive Easing) the Fed purchased two types of securities, Treasuries and MBS (Mortgage Backed Securities). The Fed did not purchase those securities from just anyone–not the US Government, not just any bank, and certainly not from people like you and me. The Fed only purchases securities from a select, and very lucky, group of investment banks called Primary Dealers.

There are currently 23 Primary Dealers, handpicked by the Fed. Almost all of them are subsidiaries of the world’s largest multinational bank holding companies, like Goldman Sachs, JPM, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, Nomura, Royal Bank of Scotland, Royal Bank of Canada, and others both domestic and foreign. If you get the idea that most of them are foreign, you would be correct. Only 8 of the 23 Primary Dealers are US based. The Fed is really a central bank to the world, as are the ECB and BoJ. But that’s a story for another day.

The Primary Dealers are selected by the Fed for the privilege of trading directly with the Fed in the execution of monetary policy. This is essentially the only means by which monetary policy is transmitted directly to the securities markets, and then indirectly into the US and world economies. To put it bluntly, the only means which the Fed uses in the transmission and execution of monetary policy is via securities trades with the Primary Dealers.

The Primary Dealers are also “tasked” with the privilege of making markets of US Government securities issued by the US Treasury. When the public bid is not large enough to absorb an issue, the dealers are required to step up and buy the balance. That’s never been a problem, especially in recent years, as the worldwide demand for “safe and liquid” US Treasury securities has seemed insatiable. That and the fact that the Fed was a buyer of a large, previously revealed quantity of Treasuries from 2009 until 2015. For the dealers it was a gravy train.

Since the advent of QE in 2008, the Fed’s monetary policy has resulted in a one way trade with the Primary Dealers. The Fed has been a buyer, an immense, constant buyer of a known type and quantity of certain securities. The Primary Dealers have been only sellers in these trades with the Fed. The Fed pays for the securities that the dealers sell to it by simply crediting the trading accounts of the Primary Dealers with newly conjured up cash that didn’t exist before the trade. The dealers are cashed out of the securities positions they held. They then can releverage that cash to buy more Treasuries, MBS, or whatever they so choose, including equities.

With their accounts constantly overflowing with the Fed’s newly created cash during QE, the Primary Dealers essentially became the conduits of a Fed permabid for bonds and stocks. Hence we have been witnesses and parties to the most rigged, artificially driven bull markets in the history of finance. Nothing else comes close. It has worked as long as confidence in the central banks’ ability to pull it off has been strong. That’s a condition unlikely to last forever.

The Fed ended outright purchases of Treasuries at the end of October 2015. However, it is a little known fact that it continues to purchase MBS. It does that because every month some of its MBS holdings are paid off. In the housing finance business, buyers of homes get new mortgages which are used to pay off sellers’ mortgages. Also, people refinancing their existing mortgages get new mortgages to pay off the old one. Old pools of MBS shrink in size when the mortgages within the pool are paid off. That includes the Fed’s holdings of MBS. Every month the Fed’s MBS holdings shrink as a result of the constant flow of payoffs of old mortgages.

To keep its balance sheet level, the Fed buys more MBS from the Primary Dealers every month. That brings the Fed’s total assets back to the amount it was, keeping the balance sheet level. But on the other side of the MBS purchase transaction, the Primary Dealers are still getting cash, just like under QE. It’s not as much cash as before, but it has been sufficient to goose the market from time to time. That permabid, while much smaller is still there. It’s the Fed’s way of trying to keep a floor of sorts under securities prices.

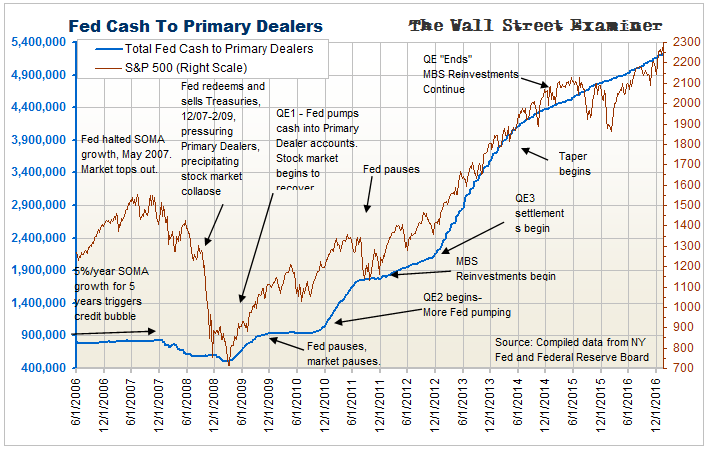

This chart shows the effect of the Fed’s purchases from the perspective of the impact on dealer cash, and thus the impact on the stock market. You can see that stocks have closely tracked the direction of dealer cash. But there were breaks in confidence in August 2015 and January 2016 that probably represent the wave of the future.

The Fed purchases forward MBS purchase contracts throughout the month, in a previously published quantity. The Fed settles all of its MBS purchases around mid month and then leaves the markets to fend for themselves at the turn of the month. In view of that pattern, the markets should tend to be rockier at the turn of the month than at mid month. Markets should strengthen at mid month during the period when the Fed settles its prior MBS purchases.

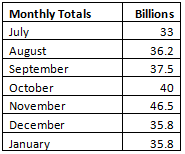

The Fed’s purchase settlements for January begin this week on Wednesday, January 18, and will run through January 24. They will total $35.8 billion. The December total was the same, but these are down from $46.5 billion in November.

They should continue to diminish in the months ahead. That’s because mortgage refinancing activity declines as mortgage rates rise. The flow of refinancing, and thus MBS paydowns, has slowed radically as a result of the recent rise in mortgage rates. The Fed only needs to buy $31 billion of MBS replacement purchases in the current month. That will result in smaller purchase settlements in February and March.

The bottom line is that that permabid under the market will shrink in the months ahead, especially if mortgage rates continue to rise. If refis dry up, the amount of purchases could fall to as low as $15 billion per month, which is the typical amount of new purchase money financing each month. Even at current amounts, the stock market isn’t getting much help. Any shrinkage of the Fed’s MBS purchases could turn the effective support for the market from semi-porous concrete into quicksand.

The increase from July to November was due to increased refinancing because of falling mortgage rates. Borrowers refinanced and paid off existing mortgages when rates fell. These payoffs resulted in larger paydowns of MBS held by the Fed. The Fed then replaced those in the following month. This cash kept the Fed’s balance sheet level while cashing out the Primary Dealers who sold the paper to the Fed. They had more cash to play with then than they do now. And they will have less in the months ahead.

Lest we think that less cash from the Fed will create a vacuum, remember that both the ECB and BoJ are still pumping money into the world liquidity pool. 13 of the US Primary Dealers are also Primary Dealers for Europe and Japan. That’s why I say QE anywhere is QE everywhere. Much of the cash pumped into the accounts of the world’s biggest banks by the ECB and BoJ finds its way to the US markets. That’s partly responsible for what seems to be a permabid for US stocks and bonds.

On the other hand, the markets can destroy money whenever confidence is shaken. We saw bouts of that in August 2015 and January 2016. Significant foreign sovereign fund liquidation appears to have played a role in the weak bond market since July of last year. There’s no real sign, nor any reason to think, that this will turn positive any time soon. Confidence is wavering around the world. China seems to be a ticking time bomb. Sooner or later, that could turn into a tsunami of liquidation that destroys money faster than central banks can print it.

The liquidity basis for the recent rise in stock prices is not clear. It may be short covering or rotation from bonds to stocks. It’s not due to a broad or strong increase in total liquidity. Therefore it is probably not sustainable over the intermediate and longer term.

The MBS purchase schedule and results can be found here.

This report is derived from Lee Adler’s Wall Street Examiner Pro Trader Monthly Macro Liquidity Report.

Lee first reported in 2002 that Fed actions were driving US stock prices. He has tracked and reported on that relationship for his subscribers ever since. Try Lee’s groundbreaking reports on the Fed and the Monetary forces that drive market trends for 3 months risk free, with a full money back guarantee. Be in the know. Subscribe now, risk free!