It is never a good thing when official sources either named or unnamed are quoted in the media as denying bailout discussions. For any bank such rumors and denials are harmful because, obviously, they are a reflection of common perception. Furthermore, most people know all-too-well the true nature of any denials, thus reinforcing only that much more the troubling perceptions in the first place.

For Deutsche Bank to be the institution in question is altogether different. When Germany’s Commerzbank, for example, was forced to request a capital injection from the state’s bailout fund SOFFIN in November 2008 that was a sign of the times. It was just another bad sign in an ocean of them. Should Deutsche Bank even get connected to something like that is perhaps a sign of renewal of those times.

Deutsche Bank is not Commerzbank; in many ways Deutsche is the last remaining remnant of what is left of the reigning wholesale, eurodollar system. Where other banks long ago saw this depression for what it was (all risk, no reward), DB was siding with central bankers and deploying “capital” into EM’s and junk bonds. The bank was reticent to reject its derivatives book, once a source of nearly all its power and strength. And it was dreams of reclaiming lost grandeur that drove the bank into its currently perilous state. When the firm first announced estimates for its coming loss in October last year, I wrote:

The net result of this toxic stew of bastardized banking is a highly negative return (revenue) environment for CB&S in 2015 beyond all scale of 2013, while its efforts to reduce assets (especially risk weighted calculations) continue to fly against its “dollar” activities. The firm managed to take the worst course possible by thinking the shrinking eurodollar system particularly post-May 2013 was an opportunity to replay lost pre-2007 financialism glory. To do that, the bank kept up its leverage and then went after the junk and EM bond bubbles with enthusiasm.

All that is forgotten in the mainstream media that wants to frame a systemically important bank’s troubles on once again regulation, or at least government action intruding into what it is supposed to be an otherwise stable and healthy environment. This weekend it was reported that Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel denied that the state would consider a rescue of Deutsche, even though the bank’s name literally means Germany’s bank.

Deutsche Bank AG shares fell sharply Monday morning on investor concerns about the German lender’s capital position ahead of an anticipated legal settlement with the U.S. Justice Department.

Any settlement with the US on fraud charges will not help, of course, but this is so much more than a legacy issue of the “dollar’s” role in the housing bubble/debacle. Lest anyone forget, it wasn’t strictly legal charges that pushed the bank into a tremendous loss and capital preservation mode last year. The media refuses to admit these facts because they fatally damage (yet again) both sides of QE – as a recovery “stimulus” and as a massive liquidity buffer denying any possibility of a global “dollar” shortage. The mainstream convention still views quantitative easing as “money printing” when Deutsche Bank shows quite clearly it wasn’t.

My own interest here is less about Deutsche Bank than it is the continued trajectory of the eurodollar system. I wrote not long ago about my thinking with regard to Deutsche Bank’s central role in the “dollar” run that started July 6 or so; today’s announcement is pretty bad, and likely just the beginning without some miracle turnaround, which adds up to nothing good about the “dollar” moving forward. Whatever negative effect Deutsche may have been having already in eurodollar liquidity, these results will quite likely speed that up.

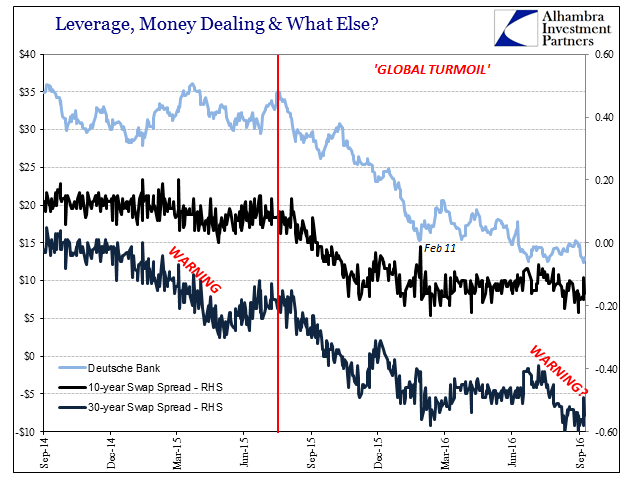

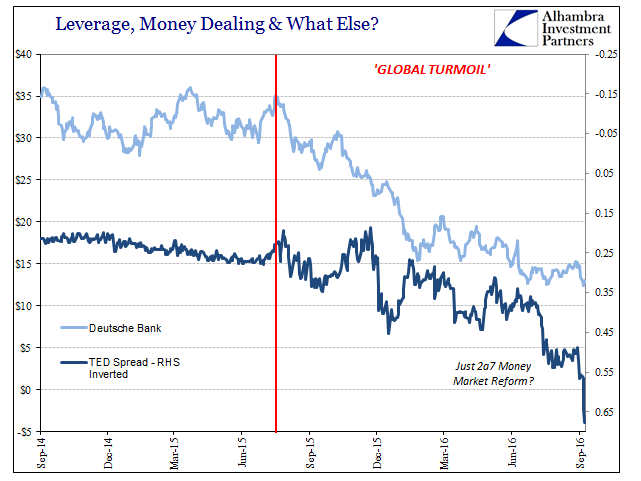

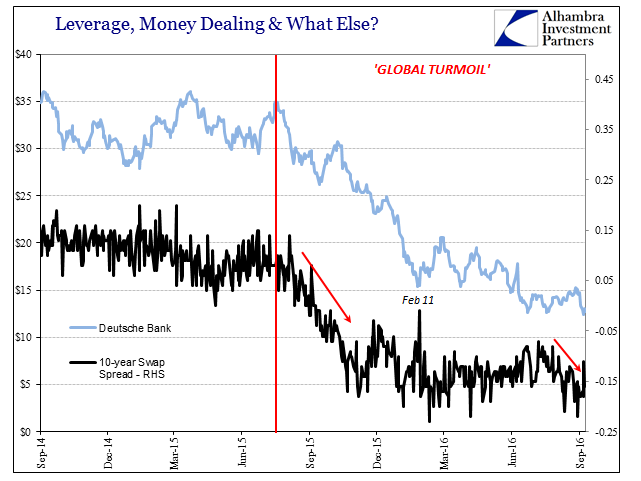

In general terms, eurodollar liquidity is the ease or hardship of balance sheet capacity; the “bank reserves” that are a byproduct of quantitative easing whether dollars, euros, or yen just don’t factor all that much (I would write “not at all” except that there is some limited value to central bankers in perpetuating the myth’s effects on expectations). As balance sheet capacity goes, so does the whole global system. And though the eurodollar is often impenetrably complex and obscured, there are a few pieces of evidence that unambiguously substantiate its increasing illiquidity.

The close correlation of “global turmoil” and negative swap spreads is not some accident of nature. Both are symptoms of the same chronic money disease. Given Deutsche Bank’s status as the largest single purveyor of balance sheet factors through derivatives and FX, we would expect such a close relationship with its own share price. It isn’t a bank run at least in the manner the general public or economists might recognize, but the processes are remarkably, dangerously similar – especially how they become self-reinforcing beyond some unknowable tipping point.

In a traditional bank run, perceptions of the bank drive depositors to withdraw from the bank’s vault of money and cash rather than trust that the bank can meet all withdrawals, sticking the depositor with some unknown scale of loss. The intensity of the run, really illiquidity, is driven by further rumors about the bank’s position. At some point, the withdrawals themselves just confirm the negative perceptions, thus locking the bank into a downward spiral toward failure.

This process recurred in 2007 and 2008, only wholesale in nature and interbank in format; it was the rare occasion that depositors were involved (Northern Rock in September 2007 being most prominent). Liquidity providers in all kinds of eurodollar formats would react to “capital” loss perceptions by withdrawing liquidity to the point that the act of liquidity withdrawal (rather than losses by the target) itself was the agent of destruction – just as in the traditional bank run scenario. That is what ultimately took down Lehman, Bear Stearns, AIG, etc.

As has been the typical mainstream reaction, Deutsche Bank is being written about right now in a vacuum as if the actions and behavior (and losses) of last year were left only to last year. When global illiquidity first popped up (again) in the second half of 2014, it was regarded in the same way – a series of purportedly random, unrelated events. They had to be strung together in a benign chain of distinct actions because convention still holds QE to be money printing. Ditching that convention has the effect of connecting all these dots as a logical and ongoing progression of a “rising dollar” that is really a euphemism for “dollar shortage.”

And it really doesn’t take too many dots to connect. This isn’t to say that Deutsche Bank is in danger of a wholesale liquidity run, only that the bank is perhaps far closer to it than anyone in the mainstream will ever admit. As I wrote last year, it really isn’t even about Deutsche Bank.