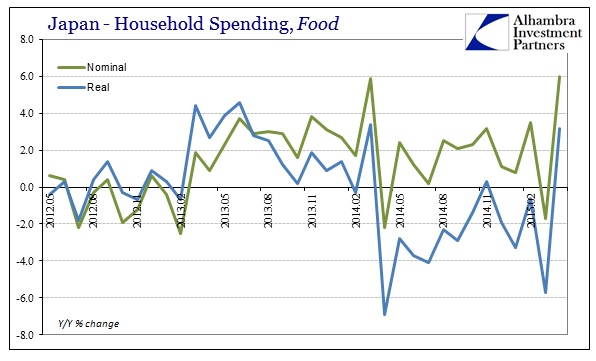

Japanese household spending increased 5.5% in nominal terms in May; 4.8% in real spending growth. That was the first monthly increase since November and since it was a positive number, and not as typically close to zero, it is being hailed as another great sign of QQE success. With Q1 GDP revised up to nearly 5%, economists are back to being confident in the monetary regime despite almost giving up on it just a few months ago.

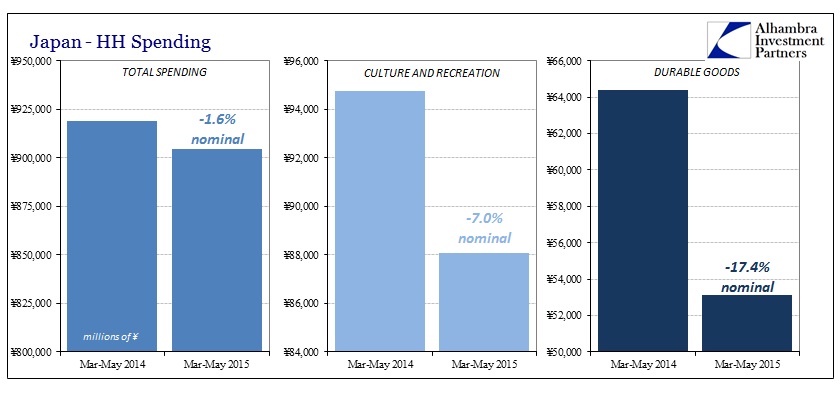

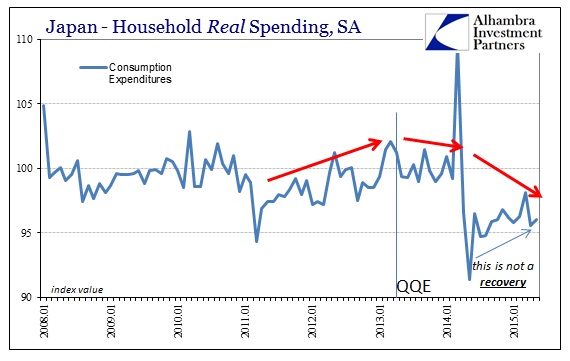

Most of that expressed optimism is still of the cautious variety, with good reason. Spending may have increased in May but that was in comparison to May 2014 and the great collapse in the economy following the tax hike. In other words, just as the -8.1% estimate for March was somewhat misleading via that base comparison, the same is true for the entire three months March to May. So with May 2015’s estimate, we can simply aggregate the entire three month period and compare the whole process in and out.

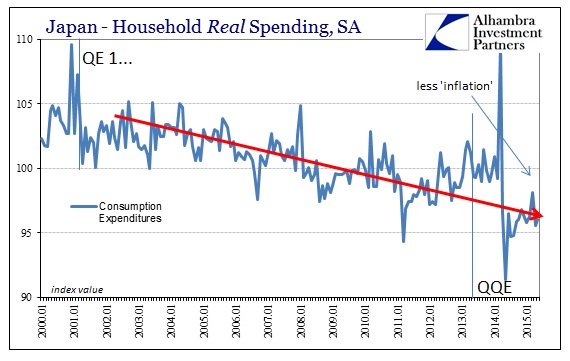

Instead of rising fortunes, household spending actually demonstrates the great hole left in the economy from QQE (not the tax cut). Overall spending in nominal terms is down 1.6% in the three months ended May 2015 vs. the same months in 2014. Even with the CPI estimated down to around 0.7% in May, though 2.8% in March, real spending in 2015 so far is certainly more than 2% below last year, if not closer to 4%. Durable goods, which were greatly affected by the tax hike, have shrunk more than 17% which shows just how much “demand” was pulled forward.

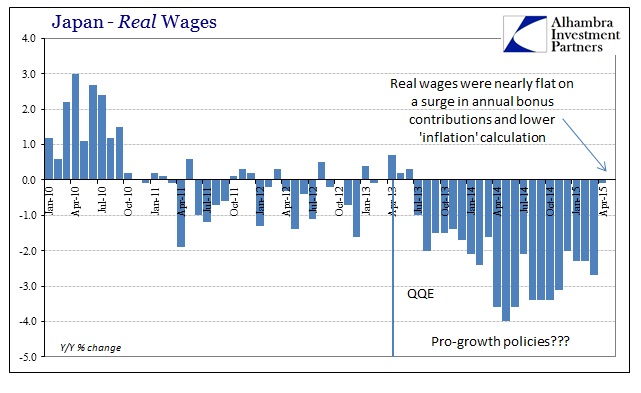

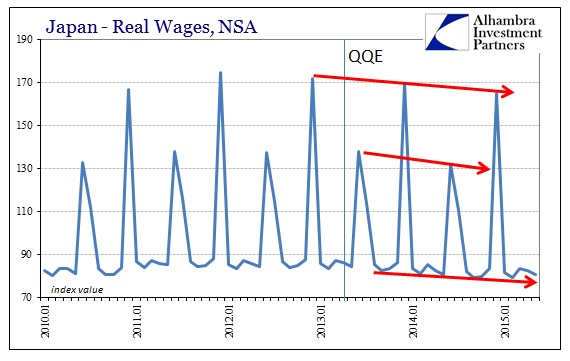

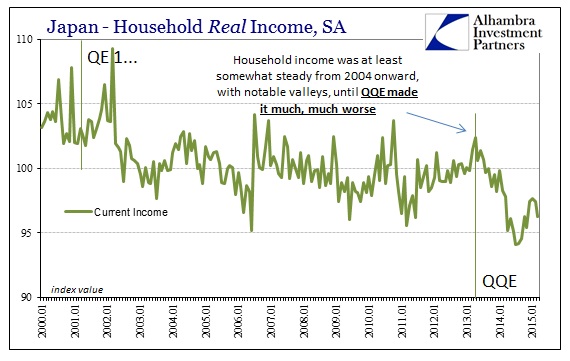

The basis for the negative redistribution is the fact that wages continue to sink. Despite almost record bonus payments in both April and May (with May’s figure revised up today to +25.2%), real wages in Japan still contracted. Real wages have not increased since the early months of QQE, which does not suggest but actually demands QQE and its intended “inflation” as responsible.

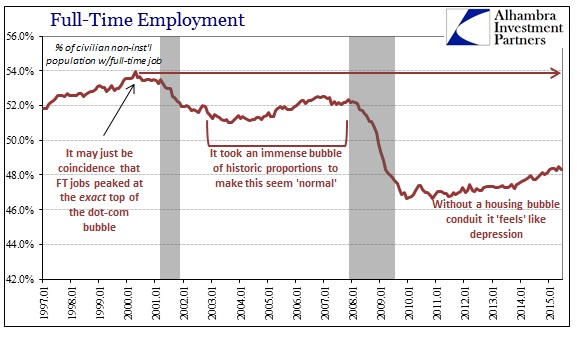

Since November, when this recovery supposedly began, total hours worked have contracted in all but two of the months; total hours in May were 1.3% below November and 2.2% below the “cycle” peak of May 2014. The yen monetarism is nothing but an illusion intended to create generic transactions as if those were the key to unlocking “idle” potential.

That is the common factor of all these monetaristic interventions. The aftermath of each is called a recovery by the standard of nothing but non-contextual positive numbers. Household spending may have risen by 5.5% in May, but that by itself is absolutely meaningless, even if there were no base effects to consider. It is not a recovery or even resembling the stirrings of one since it takes no account of the direct devastation in the economy left by QQE in the first place.

There is very much a broken windows element to all this, as these central bank interventions blow apart the economy and then take credit for the agonizingly slow rebuild. In Japan, it is so obvious that it takes only a committed ideologue to ignore it.

The reason the tax cut was such a drastic limitation was because of QQE’s depression of wages as the yen-driven cost of living immediately impoverished the Japanese. If QQE had even begun to work by that point, the tax cut would have been largely a non-factor, but, as the durable goods estimates show, only a year into the experiment Japanese households were already at the mercy of a small marginal tax increase and thus reacted violently (in an economic frame) to it against all expectations. A truly strong and fortified economy would have weathered the tax change, which was what every economist and policymaker thought would occur.

You see it in spending, income or almost whatever economic account; QQE destroys the economy and then is quick to credit any upswing in its aftermath as “proof” it actually worked. If there is proof in there, across all these observations, it is how much monetary instability of this type really is the modern version of Bastiat’s warning:

With Japan, the demarcation of QQE makes all this very plain and observable, but it is no less true anywhere else monetarism dominates. The Great Recession itself was of similar construction, as monetary redistribution in the form of the housing bubble led to massive American impoverishment that we still, five years after its declared end, are enduring (and maybe not so much lately). Just as Japan is now, the smoldering ashes of the US economy was directly related to that redistributive monetarism and financialism but central bankers have only given themselves account for the minimal positive numbers that have followed thereafter; and almost exclusively without any context to them (as context ruins the narrative).

The entire theory of monetary and fiscal “stimulus” is that it is better than nothing, to at least try to force transactions out of “idle” assets (whether real or financial). The assumption isn’t just wrong it is tragically so. It is not better in any case to try to force economic growth through redistribution, a very negative and disruptive factor, even when measured against doing nothing (the assumption on its face is a bastardized understanding of an economy to begin with, as if a recovery cannot occur of its own accord without some statist “push”; that actually gets to the heart of the matter, as if the recovery came and was robust all its own it would greatly diminish and curtail the power of economist central planners and central bank socialism, therefore they only “allow” a recovery of their own choosing, all or nothing). Almost like a black hole, we can see monetary redistribution by the damage left in its exposure. Further, we can actually measure the size of the monetary experiment by the amount of that damage as Japan seems intent on further and further establishing.