In what can only be an intentional trial balloon, the Abe government in Japan is making noise about delaying the next scheduled tax increase. Considered to be one of the important “arrows” in Abenomics, this is an especially stark admission that orthodox economics has not (yet again) delivered on its promise. When QQE was started in April 2013, there were no doubts, none, or critical comment from inside the Bank of Japan or Abe’s administration, just as there were no doubts expressed in the mainstream media. If orthodox economists said this was going to lead to recovery, such projection was taken as objective “science.”

Given that Q3 GDP for Japan will be released on Monday, I have no doubt at all that Abe and his cabinet, as well as Bank of Japan officials, are fully versed on the disaster it is likely to be. Working backward, they “had” to leak the tax delay for perceptions that there might still be at least some credibility to it all.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is likely to delay a planned increase in the nation’s sales tax, judging that the economic recovery remains too fragile to weather a further blow, a government official close to Abe’s office said on Tuesday.

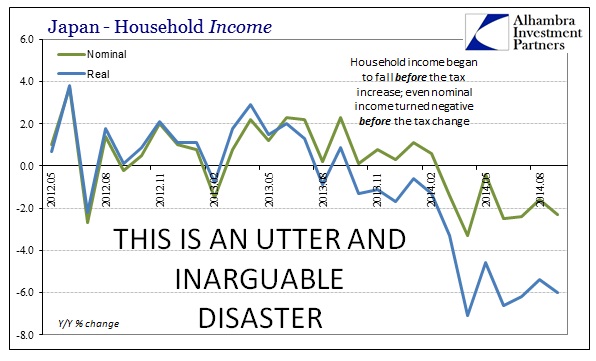

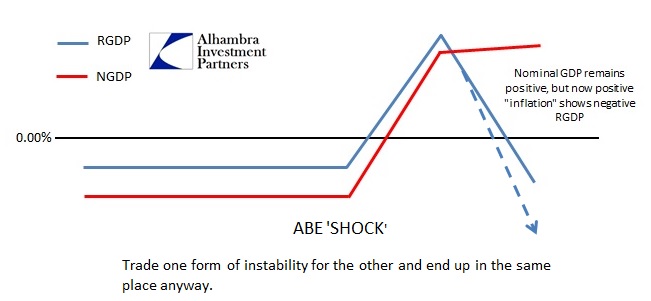

At this point can it even be called a “recovery?” Recent indications more than suggest re-recession based on the very “inflation” Abe and the Bank of Japan were entirely sure they wanted.

While Abe’s support has slipped in recent weeks, the dip hasn’t lifted the opposition and opinion polls indicate his ruling coalition would return to power in a new vote. With the economy struggling to gain momentum and the government considering unpopular measures to contain the world’s biggest debt burden, Abe may be seeking to strike before his support softens further.

“They may think the economy is going nowhere, so better now than later, also the opposition is in bad shape,” Robert Dujarric, director of the Institute of Contemporary Asian Studies at Temple University in Tokyo, said by e-mail. [emphasis added]

To me that confirms the disaster in the Japanese economy, and that even now its most strident supporters are not just expressing doubts but may be outright turning against it. Undoubtedly, Japanese officials are aware of last week’s election in the US and how economic dissatisfaction was the primary concern. In other words, the combined effect of the “possible” delay in the tax increase at the same time as an “unexpected” snap election is an extremely dour sentiment among the very officials that promised nothing but the opposite for two years now.

And we should not forget the Bank of Japan’s recent increase in the pace of QQE, either. The nervousness, even panic, among the orthodoxy in Japan is palpable. The cumulative effect is simply that finally these policymakers have been forced out of their models and into reality. Unfortunately, that may not be enough as BoJ confirmed by expanding its debasement. We can only hope that voters come to their senses and see this for what it is – national impoverishment.

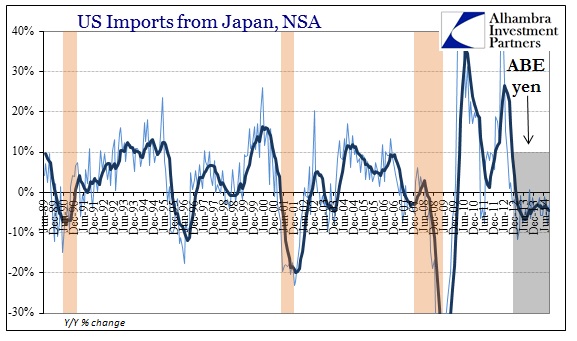

Under Abe, the yen has fallen to a seven-year low, fueling a jump in Japanese exports and a surge in corporate earnings. The benchmark Topix stock index has gained more than 70 percent since Abe was elected in December 2012 and closed at a six-year high today.

That stock prices are at a six-year high says a lot about the growing divergence between finance and the real economy that is actually quite global. It is probably too much at this stage to expect the media to be more factual in reporting, especially as they somehow continue to uncritically assume that QQE has been “fueling a jump in Japanese exports.” Even after all that has happened, orthodox commentary somehow still passes for convention. There is, after all, a world of difference between nominal and real, and that difference is everything that is wrong with the idea that “inflation” is somehow anything other than a negative factor.

If you think demand drives the economy then inflation sounds like it should be a powerful tool toward that idea. That is particularly true when you believe in a simplistic world with all sorts of caveats and of course ceteris paribus. The orthodox version of inflation is simply that people react to expectations of inflation rationally; that is they know prices will go up in the future so they instead buy things today. Better yet (for the orthodoxy, not actual people) they will borrow funds to buy today because rapidly rising prices are supposedly that powerful. However, rationality is not limited to one alternative.

In some respects, that is what happened in the 1970’s especially on the corporate side. Companies borrowed for inventory, and built up huge inventory piles because commodity prices were killing them. That is where this all falls apart, of course, in that economists see that “killing them” as actual growth because a company did something that created generic activity. But what the company actually did was take the lesser of two evils, which means it was still a very negative factor. Keynes destroyed his own philosophy by believing that all that matters is the short run.

It’s no different on the consumer side, as people may want to act as orthodox economists intend and to spend now to protect themselves (Q1’s now long gone “surge”) from this nefarious price instability – but without actual income they simply cannot as demand is not just willingness, it also needs ability. Somehow orthodox economics simply expects that this negative redistribution will all take place at once, so incomes and prices never stray too far. That has never happened before, especially the 1970’s here or Japan right now.

Further, the economy in 2014 is pretty open, so even companies that may have reacted “favorably” to price instability long ago no longer have to. Instead of stockpiling inventory today, a company can move to cheaper labor sources or automation, or use some other method of cost control. So orthodox economics again assumes only one simple outlet to counteracting fears over company profits when the real world opens up so many options for profitability (none of which are truly expansionary). The greater the instability the less favorable labor and income, and therefore the whole of the economy.

You simply cannot encourage sustainable economic growth by “killing them.” The preponderance of negative factors in the orthodox toolkit is all you need to know about its actual effectiveness. And where it does seem to work, that is only either a temporary transition period or bubbles. In either case the net result is to be worse off for having undergone the transition or bubble. Authorities in Japan may not yet be to that interpretation, but they are getting there and not of their own volition.