OK, I don’t see a whole lot of comprehension out there, so let’s try and link the obvious: employment to shale to plummeting oil prices to the debt the shale industry was built on (and which is vanishing). I know, people look at the US jobs report today, and at the stock exchanges (Europe up some 2% across the board), and think salvation has landed on their doorstep, but the true story really is very different.

The EU markets are up because of US job numbers + the expectation that Draghi will launch a broad QE in January. But US jobs are far less sunny than meets the eye at first glance, and the Bundesbank will not all of a sudden do a 180º on ECB stimulus options. Ergo: a lot of European investors are set to lose a lot of money.

Anyone notice how quiet Angela Merkel has become about the QE debate? That’s because she doesn’t want to be caught stuck in a losing corner. Even if the Bundesbank would give in to Draghi, and chances are close to zero, there would be multiple court cases in Deutschland against that decision, and chances are slim the spend spend side would win them all. That’s the sort of quicksand an incumbent leader like Merkel wants to avoid at all cost.

But let’s leave Europe to cook itself, and its own goose too. What’s happening stateside is more important today. First, Marc Chandler has a good way of putting what I have said for as long as oil prices started testing ever deeper seas: the danger to the industry is not even so much falling prices, it’s financing both existing and future endeavors. Shale is a leveraged Ponzi, that’s its most urgent problem. Even if shale could break even at low prices, financiers and investors would still leave the building.

Both shale oil and gas have two big problems: 1) projects are based on highly optimistic returns, and 2) they are financed with very large and leveraged debt loads. With WTI prices now at $66 a barrel, and the first Bakken prices below $50 a barrel having been signaled, the entire industry starts resembling a house of cards, a game of dominoes and/or a pyramid shell (pick your favorite) more by the day. Chandler:

[..] Marc Chandler says the energy sector has just suffered its own Minsky moment. And while he doesn’t expect it to take down the stock market, the slide in oil could have a serious impact on the high-yield bond market. Minsky moment is a term coined by Pimco economist Paul McCulley in 1998, and it refers to a point when a period of rapid growth and risk-taking leads to a sudden turn lower and a crisis. Chandler, global head of markets strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman, says that is precisely what is happening in crude oil. “Many people a couple years ago, a year ago, were saying that oil prices could only go up – ‘we’re in peak oil’ – meaning that we’re running out of the stuff. So a lot of things were leveraged based on oil prices that can only go up. Sort of like house prices—’they can only go up.’ So what happened is, because people held this as a deep conviction, they leveraged up,” Chandler said.” [..] “The big risk now to our shale is not going to be that the price of oil drops so far that it’s not going to be profitable,” he said. “The weakness, the Achilles’ heel, is that they don’t get the cheap funding anymore.”

Even Nature magazine this week gave it a shot, and tried to lend scientific credibility to a certain view of shale. Here’s the editorial:

[..] The International Energy Agency projected in November that global production of shale gas would more than triple between 2012 and 2040, as countries such as China ramp up fracking of their own shale formations.

[..] Academic journals are filled with earnest projections about future energy dynamics, which usually turn out to be wildly inaccurate. Even worse, governments and companies wager billions of dollars on dubious bets. This matters because investment begets further investment. As the pipework and pumps go in, momentum builds. This is what economists call technology lock-in. [..] Nature has obtained detailed US Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts of production from the nation’s biggest shale-gas production sites. These forecasts matter because they feed into decisions on US energy policy made at the highest levels. Crucially, they are much higher than the best independent academic estimates. The conclusion is that the US government and much of the energy industry may be vastly overestimating how much natural gas the United States will produce in the coming decades. [..] The EIA projects that production will rise by more than 50% over the next quarter of a century, and perhaps beyond, with shale formations supplying much of that increase. But such optimism contrasts with forecasts developed by a team of specialists at the University of Texas, which is analysing the geological conditions using data at much higher resolution than the EIA’s.The Texas team projects that gas production from four of the most productive formations will peak in the coming years and then quickly decline. If that pattern holds for other formations that the team has not yet analysed, it could mean much less natural gas in the United States future.

And then an article:

Natural Gas: The Fracking Fallacy

When US President Barack Obama talks about the future, he foresees a thriving US economy fuelled to a large degree by vast amounts of natural gas pouring from domestic wells. “We have a supply of natural gas that can last America nearly 100 years,” he declared in his 2012 State of the Union address. [..]

Over the next 20 years, US industry and electricity producers are expected to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in new plants that rely on natural gas. And billions more dollars are pouring into the construction of export facilities that will enable the United States to ship liquefied natural gas to Europe, Asia and South America.

All of those investments are based on the expectation that US gas production will climb for decades, in line with the official forecasts by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). As agency director Adam Sieminski put it last year: “For natural gas, the EIA has no doubt at all that production can continue to grow all the way out to 2040.”

But a careful examination of the assumptions behind such bullish forecasts suggests that they may be overly optimistic, in part because the government’s predictions rely on coarse-grained studies of major shale formations, or plays. Now, researchers are analysing those formations in much greater detail and are issuing more-conservative forecasts. They calculate that such formations have relatively small ‘sweet spots’ where it will be profitable to extract gas.

The results are “bad news”, says Tad Patzek, head of the University of Texas at Austin’s department of petroleum and geosystems engineering, and a member of the team that is conducting the in-depth analyses. With companies trying to extract shale gas as fast as possible and export significant quantities, he argues, “we’re setting ourselves up for a major fiasco”.

The scientific ring to it is commendable, but this misses quite a few things. They cite David Hughes, but leave out the work of Rune Likvern, without whom in my opinion no true – scientific or not – view of the shale industry is complete. But okay, they tried, in their own way, and their conclusions may be a bit softened, but they’re still miles apart from those of either the industry’s PR, or the EIA.

And then we move to the next link: that between shale and jobs. Because that’s where falling oil prices start to go from joy for the whole family to something entirely different.

What happens if the US shale industry crumbles under the weight of its own leverage? Most people will probably think: we’ll just start buying from that oversupplied world market again. But it’s not that easy, that leaves out one big issue. American jobs.

And we can take it straight from there to today’s hosannah heysannah BLS report. Which, however, has issues that don’t show up at the surface. Tyler Durden:

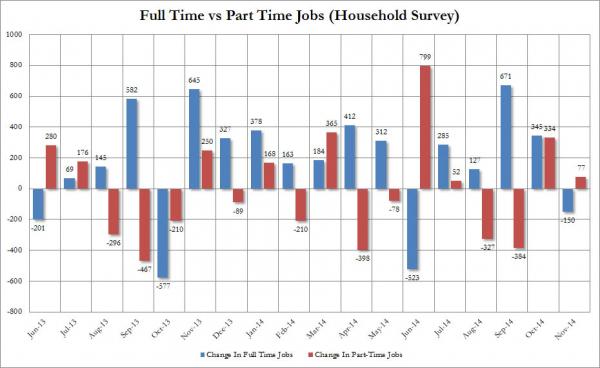

Full-Time Jobs Down 150K, Participation Rate Remains At 35 Year Lows

While the seasonally-adjusted headline Establishment Survey payroll print reported by the BLS moments ago may be indicative of an economy which the Fed will soon have to temper in an attempt to cool down, a closer read of the November payrolls report shows several other things that were not quite as rosy. First, the Household Survey was nowhere close to confirming the Establishment Survey data, suggesting jobs rose only by 4K from 147,283K to 147,287K, and furthermore, the breakdown was skewed fully in favor of Part-Time jobs, which rose by 77K while Full-Time jobs declined by 150K.

And then for those keeping tabs on the composition of the labor force, the same adverse trends indicated over the past 4 years have continued, with the participation rate remaining flat at 62.8%, essentially the lowest print since 1978, driven by a 69K worker increase in people not in the labor force.

So according to the BLS Household Survey, the US lost 150,000 jobs, while the Establishment Survey, prepared by the same BLS, shows a gain of 321,000 jobs. Yay! pARty! But we’ve been familiar with all the questions surrounding the jobs reports for a long time, so that’s not all that interesting anymore.

Still, when you see that again most of the jobs that were allegedly created are low paid service jobs, and that wages are not going anywhere, you have to wonder what is really happening. Well, this. The vast majority of new US jobs since 2008/9 have come from energy- and related industries, which makes them a dangerously endangered species now oil prices or down 40% and falling.

Tyler Durden ran the following on Wednesday, and I think this is very relevant today:

Jobs: Shale States vs Non-Shale States

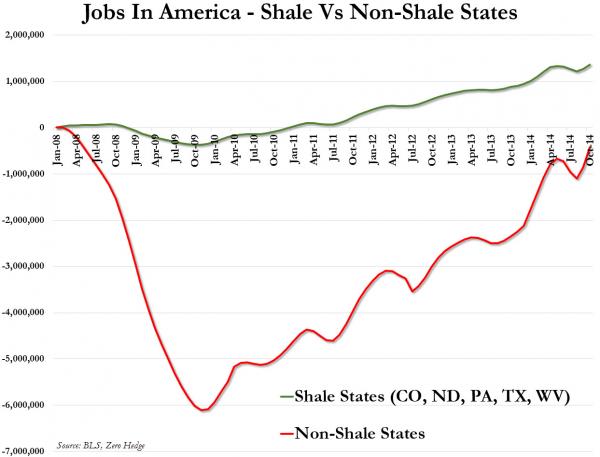

Consider: lower oil prices unequivocally “make everyone better off”, Right? Wrong. First: new oil well permits collapse 40% in November; why is this an issue? Because since December 2007, or roughly the start of the global depression, shale oil states have added 1.36 million jobs while non-shale states have lost 424,000 jobs.

The ripple effects are everywhere. If you think about the role of oil in your life, it is not only the primary source of many of our fuels, but is also critical to our lubricants, chemicals, synthetic fibers, pharmaceuticals, plastics, and many other items we come into contact with every day. The industry supports almost 1.3 million jobs in manufacturing alone and is responsible for almost $1.2 trillion in annual gross domestic product. If you think about the law, accounting, and engineering firms that serve the industry, the pipe, drilling equipment, and other manufactured goods that it requires, and the large payrolls and their effects on consumer spending, you will begin to get a picture of the enormity of the industry.

Simply put, this means 9.3 million, or 93% of the 10 million jobs created since the recession/depression trough, are energy related.

I’ve been saying for weeks that lower oil prices would not be a boon but a scourge for the US economy, for several different reasons, and this is a big one. The losses to investors, the restructurings and bankruptcies, and perhaps even the bailouts, are a very much interconnected and crosslinked other. There’s no resilience – left – in a system like this, it bets all on red, and that makes it terribly brittle.