I have referred to the June 2003 FOMC meeting many times before and I suspect that I will continue to do so long into the future. It was one of those events that should be marked in history, truly relevant to the future developments that became panic and now sustained economic decay. It’s as if the committee members at that time anticipated their current powerlessness – yet did nothing about it. Their preferred course from that moment until August 2007 was relieved ignorance.

Despite the fact that the dot-com recession had ended more than a year and half before that gathering, the FOMC voted at that time to lower the federal funds target to just 1%. It was a serious difference in policy and something that nobody at the table seemed able to have imagined prior (not the least of which because they couldn’t ever explain the problem). Not only was the economy seemingly stuck after what was a really mild recession, there was the still looming implication of a slow-motion stock crash that for orthodox economists always conjured images of 1929. The FOMC saw sluggish recovery and were adamant about using monetary policy (as they understood it) to make sure the dot-com bust did no more damage than the first truly “jobless recovery.”

Since this was a paradigm shift in monetary policy, the Committee was forced to confront not just what it was doing but what it might someday “have” to do beyond it. The Bank of Japan had gone into QE as a world’s first just two years before, but until June 2003 nobody thought it would possibly apply to anywhere but Japan. Voting to lower the target to 1% provided that sober realization, suggesting if only for a moment of unusual clarity a non-trivial possibility that their confidence in themselves might not be as deep as they believed.

Chairman Alan Greenspan was blunt in his summation of the prospect, for once (likely because it was private) admitting that what lay ahead of them below 1% was not well understood. He had good reason to be apprehensive given the circumstances of that day:

One is that I don’t think we know enough about how the private financial system works under these conditions. It’s really quite important to make a judgment as to whether, in fact, yield spreads off riskless instruments—which is what we have essentially been talking about—are independent of the level of the riskless rates themselves. The answer, I’m certain, is that they are not independent. But how their dependency functions and how those spreads behaved in earlier periods is something I think we’ll need to know more about. The reason is that I don’t believe, as I said before, that we can construct an effective preemption strategy. Well, we can construct a strategy, but I’m fearful that it would not be very useful.

Greenspan raised this point in response to Dallas Fed President Robert McTeer’s report that banks and businesses in his district were resisting the Fed’s moves before ever getting to 1%. Some of that was associated with what the Committee and Greenspan called uncertainty, but in truth Greenspan (as in the quote above) was not entirely unsympathetic to what “ultra-low” might mean as potentially very different than more normal monetary operations – with good reason.

Unlike Ben Bernanke who was far more assured of himself during that discussion, Greenspan was willing to admit that there was much they didn’t know about the true systemic nature at and around the zero lower bound. Further, in anticipating that there just might be a need to find out, he tasked the Fed at least rhetorically to do just that:

What is useful, as has been discussed, is to build up our general knowledge so that when we are confronted with the need to respond with a twenty-minute lead time—which may be all the time we will have—we have enough background understanding to enable us to make informed decisions. We need to know how the system tends to work to be able to make the necessary judgments without asking one of our skilled technical practitioners to go off and run three correlations between X, Y, and Z. So I think the notion of building up our knowledge generally as a basis for functioning effectively is exceptionally important…Even if we never have to use the knowledge for the purpose of fighting deflation, I will bet that we will find it useful for other purposes.

Did they? Here’s former Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher, McTeer’s replacement, on CNBC today:

Fisher said Fed policymakers did not anticipate the scope of easy money’s impact on the financial sector.

“Bank’s interest margins are being hammered. Money-market funds are trying to squeeze out a return. This is the kind of stuff, to be honest, sitting at the table, we did not foresee at the FOMC,” he said, referring to the Federal Open Market Committee.

Why didn’t the Fed ever do what Greenspan suggested in 2003? The answer is a combination of hubris and institutional/ideological inflexibility. On the first part, June 2003 represented the tail end of both the lingering recessiveness of the dot-com recession and dot-com bust – to which the Fed, as they always do, assigned their own actions as the ultimate saving grace. In other words, they believed that they had protected the world from a worse fate when there is and was every reason to suspect (starting with the already raging housing bubble and “global savings glut”) otherwise. As they saw it, they knew all they needed to know since they had already proven to themselves the monetary genius capable of such precision navigation.

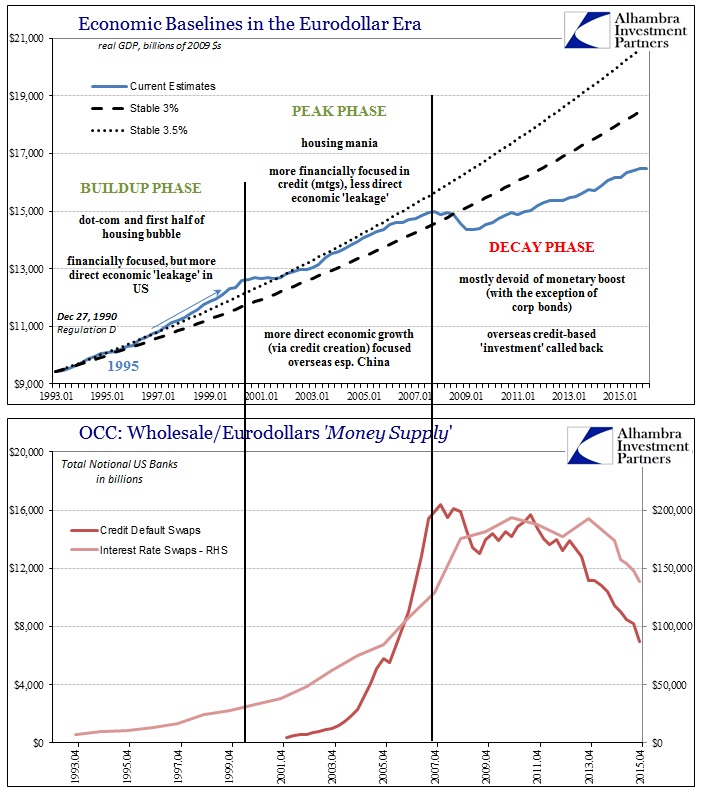

Ideologically, they were never going to undertake a full investigation anyway. It was only two years after that they shut down completely M3 and all official reference to the monetary pieces that actually mattered. Greenspan “got us out of the dot-com’s” using just the federal funds target, so why bother with eurodollars, credit default swaps and repo collateral chains? The waving of the target wand was all they thought would be necessary “next time” while figuring themselves so good there would never be a next time (let alone something far, far worse). Bernanke’s performance in public starting at the housing bust (“subprime is contained”; “worst is behind us”; etc.) was this characteristic put into action.

Because of that intentional, self-limiting blindness the FOMC when confronted in 2007 with nothing they were familiar with did exactly as Greenspan admonished in advance. The FOMC especially under the staunchly unmovable Bernanke was left just making it up as they went (and failing time and time and time again). By the end of 2008, sifting through all the wreckage, what did they do? They followed Japan even though in June 2003 they had once declared everything that was supposedly wrong with Japanese QE.

One lesson that I drew from Japan was that not only did the Japanese get down to zero on the interest rate and not only did they try each new policy and say they were going to take it back, they didn’t give any sense of where they were going. They were lurching from one policy to the next, each time saying that they didn’t think it would work. So I do believe it’s important that we decide before we get to the point where such policies need to be triggered—and I’ll come to that issue next—at least on a very rough sequence of what we will do and how we will talk to the public about it. We don’t need to be very specific; but before we begin to use nontraditional techniques, I think we need to talk about them publicly and create a sense of continuity and confidence in our policymaking, which I believe was absent in Japan.

That was Federal Reserve Board Governor Donald Kohn’s view and despite being adamant about it in 2003 it describes very well Ben Bernanke’s Fed in 2008 (or 2010; or 2012) initiating their “nontraditional techniques.” What the Fed failed to realize in 2003, and even 2007, was that failing to forestall full-blown (interbank) panic removes any possibility of “a sense of continuity and confidence” in any policymaking.

Because they were so unprepared for 2008, we have been doomed to follow Japan, a growing possibility that another Fed President and current FOMC member brings up recently:

Indeed, Mr. Bullard has fretted for years that the United States and other major economies may be stuck with low interest rates for some time to come. In an interview last week, Mr. Bullard said he wants to raise rates. He really does. It just seems as if the necessary conditions keep slipping away.

After pushing to raise rates at the beginning of the year, he voted against a rate increase in April and he said he’s still thinking about June. “If you talk to people in Tokyo, they say, ‘Well, we’ve been through this and tried all these things and you guys are just following us,’” he said in the interview. “I hope that’s not exactly true.” [emphasis added]

It is true and it is something that the Fed unbelievably contemplated almost thirteen years ago, vowing if they ever had to it would be different. So much for that. Wallowing in their own monetary ignorance, instead these “best and brightest” removed all inquisitiveness, leaving for themselves only greater constraint so that long after it was too late their only option was to follow Japan into what they already knew didn’t work. Worse, they did so in exactly the same way as the Bank of Japan they openly criticized in 2003:

Another problem in Japan was that the authorities were overly optimistic about the economy. They kept saying things were getting better, but they didn’t. To me that underlines the importance of our public discussion of where we think the economy is going and what our policy intentions are.

Governor Kohn was apparently unable to imagine how non-Japanese central bankers might also possess (if not only possess) great ability to undermine themselves and their assumed power; especially in situations where they should not be so sure what power they might actually possess in the first place, essentially the central point of this discussion in June 2003. Alan Greenspan’s warning at that meeting could easily be distilled as “make sure you can actually do what you say you can do before you actually have to do it.” Unfortunately, that would require honest assessment, which is something the Fed has demonstrated itself (over and over) never quite capable of producing. Instead, Kohn’s words might very well have been repeated by some other central banker in some other global hotspot criticizing Janet Yellen in 2014, 2015 and still in 2016. Apparently it was better to fail as the Bank of Japan failed then to do something with an actual chance of success – like let markets clear out imbalances while undertaking honest understanding of the actual run of banking and global money (and now its material deconstruction). It’s not like there hasn’t been ample time for this, inching closer every FOMC meeting toward a full lost decade despite that institution years before its start essentially warning itself not to do what it has done.

To date there have been no repercussions for any of this. They really don’t know what they are doing and these people will not stop no matter how far they sink us and how absurd they act in doing so. It reminds us once more why the recovery is now only political.