Last month’s retail sales report for May was taken as the definitive sign that the slump had passed and that the conventional view of the jobs market was finally, if surprisingly belatedly, taking shape. It did not matter to economists that the only basis for that interpretation was seasonal adjustments, which had produced a huge disparity with the unadjusted set. I wrote then:

There is a lot about this “cycle” which is totally upside down, but retail sales in May just might represent the apex of the Orwellian transformation; all on the say so of seasonal adjustments. The worst data in years, comparable only to the worst economic experiences in recent history, are now counted as a “surge” in spending and cause for both optimism and doom.

The mainstream interpretation sounded far more appealing despite its rather easily apparent illegitimacy:

U.S. retail sales surged in May as households boosted purchases of automobiles and a range of other goods even as they paid a bit more for gasoline, the latest sign economic growth is finally gathering steam.

With, again, statistical fancy as the only foundation for that recovery storyline, it is decidedly not unexpected that June would find its opposite effect. That is the nature of seasonal adjustments, as what they give alone in one month must be undone the next (when “surges” aren’t really surges but statistical variation only). The decline in the month-over-month retail sales for June thus completes the trip, though the despair in the mainstream is almost psychotic with its “shock.”

A sample of just some headlines:

CNBC: Markets Jarred by Surprisingly Weak Retail Sales

BloombergBusiness: Retail Sales in U.S. Unexpectedly Fall on Broad-based Drop

MarketWatch: Retail Sales Shock Wall Street, Slide For First Time in Four Months

Most of the articles themselves are far more melancholy than has been typical of the repeated and incessant “unexpected” results. As I noted yesterday in viewing same store sales, which almost perfectly pegged this retail sales report, the narrative has decidedly shifted as “transitory” and “lower oil prices” and even the dominant view of jobs has now almost disappeared. There is something greater going on here and even the orthodox economic world is starting to appreciate that, if it is yet unready to fully comprehend what that might mean.

Not all absurdity has disappeared, however, as there has been, as if by coordination, a new flock of excuses. Where weather and some remote port strike were “to blame” for the first part of 2015, June is apparently undone by Memorial Day and, get this, the later end to the school year. Bloomberg:

An early Memorial Day holiday that may have boosted sales in May at the expense of last month, and a longer school year caused by the harsh winter probably contributed to the more subdued sales performance for the quarter. Stronger gains in incomes will probably be needed to give consumer spending, which accounts for almost 70 percent of the economy, a bigger lift heading into the second half of the year.

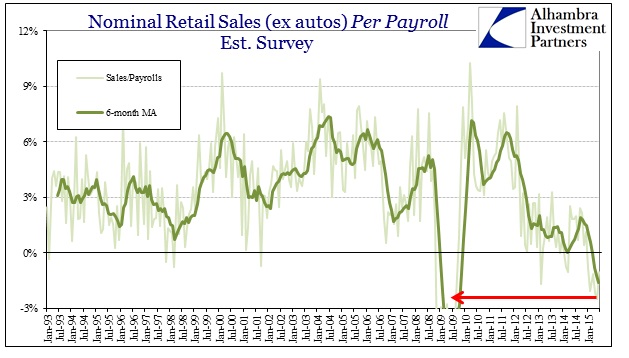

The fact that we are now in June and that new preposterous excuses are being used by economists to rollover old versions is gaining evidence of the US already in recession, especially the consumer. That last sentence quote immediately above is all that is necessary to destroy all forecasts otherwise, as the “greatest jobs market in decades” has been stated as exactly that great for far more than a year now, but yet “stronger gains in incomes will probably be needed”? That jarring dissonance is a real economic phenomena for how a highly adjusted statistical data series (the Establishment Survey and related unemployment rate) may be wholly wrong.

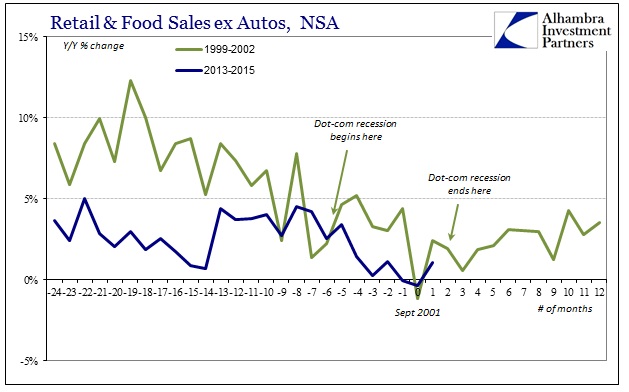

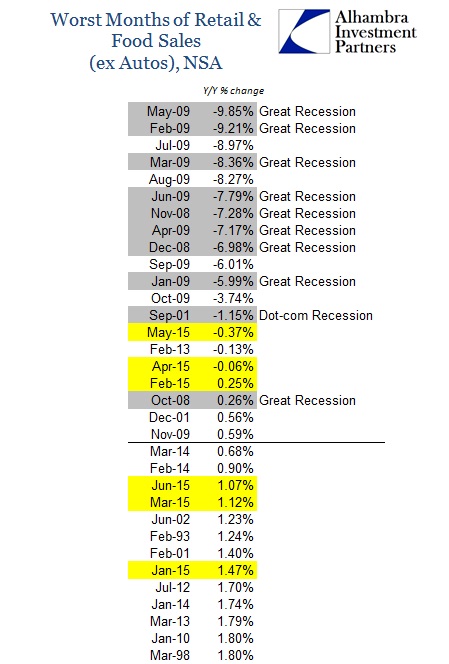

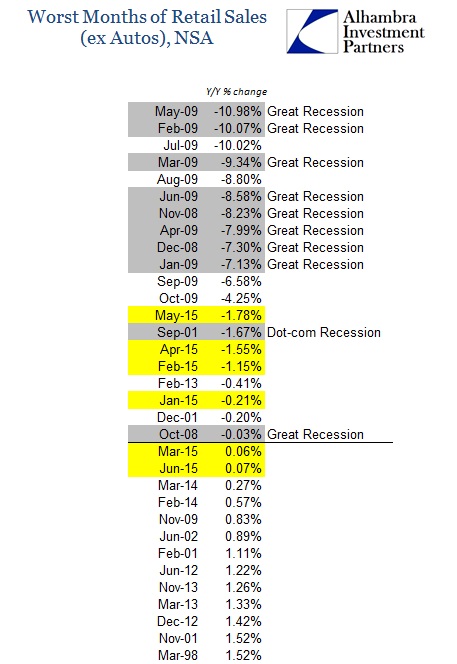

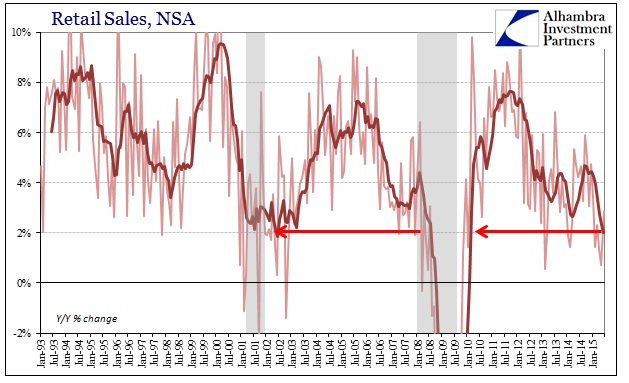

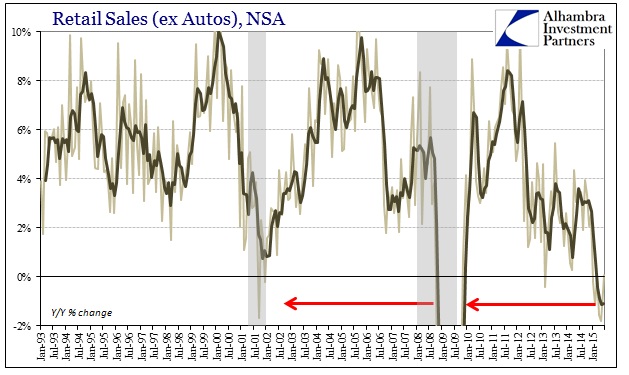

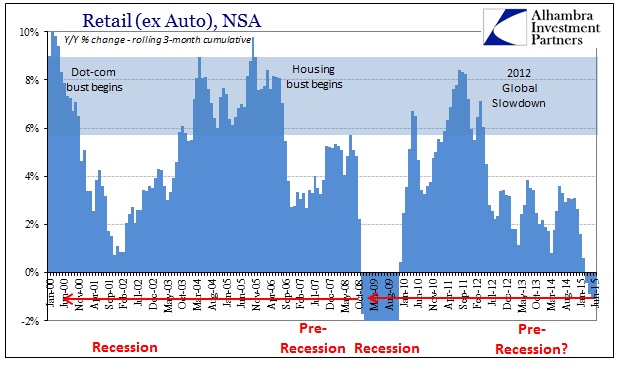

It is reasonable, given the actual spending and even income data, to assert that the US economy might, at this moment, already be in mild recession. It is at least uncontroversial now that economists might begin to actually contemplate that this is a real possibility. Retail sales (ex autos) have now been nearly flat for all of 2015; ex food and autos negative or zero for the full year so far! The drop in retail sales (with food, ex autos) is at least as severe as the whole of the dot-com recession already (“inflation” or not).

As I have chronicled throughout this year, all six months of 2015 for retail sales reside in the lowest echelon of the entire series going back to inception in 1992. The only months worse than now are the collapse portion of the Great Recession and its immediate aftermath, an uncompromising list that suggests far more than trivial recessionary probabilities.

The fact that this decay has lasted six months (and really eight going back to the first interruptions during the holiday shopping period) can no longer be interpreted as a minor and temporary “slump.” I have little interest in the semantics of the word “recession”, but it is not, contrary to popular opinion, two consecutive quarters of negative GDP (not the least of which is because GDP does not get revised of its trend-cycle upward bias until long after recession is obvious and declared). A recession is essentially a serious and sustained deviation from the true potential path (as opposed to the mistaken Phillips Curve projections that pass for the concept).

That definition would actually count for almost all our economic experience since the 2012 slowdown, but it has taken new emphasis just this year in direct violation of the payroll interpretation. Any economic anomalies so far since that slowdown are not the “winters” and “unexpected” weakness but rather anything to the higher side – the repeated and almost permanent use of “unexpected” as an apology these past three years demonstrates that fact quite well. Where 2014 might have been a “slump”, and thus a grave warning, 2015 is so far, to my view, mildly recessionary.

That distinction, owing in great part to the time factor, is actually more ominous that it sounds. Lingering dissociation with good economic behavior is itself a problem, but so far we have yet to see and experience the usual recessionary forces act upon other economic areas; severe inventory correction and other massive cost-cutting moves on the part of businesses, leading up to a sharp revisit of negative employment (we may have already and actually experienced a minor dip in employment already, though hidden amongst the trend-cycle bias of the payroll reports). In short, we may have a mild recession already without yet close to the full extent of a recessionary downswing.

I have attributed that to attrition, the protracted and unsatisfied weakness of what really appears to have been an extended and elongated “peak” cycle. In that view, what becomes more relevant is not groping for somehow the removal of that attrition, trying to further and further excuse the immediate weakness, but rather to begin searching the spectrum of possibilities about the length and ultimately the depth of this process. The fact that consumers, especially, had not experienced much if any recovery since the Great Recession more than five years ago already pushed toward an even more drastic downside likelihood. Combined, there are consumers whacked by no recovery and now again into what may be a mild recession, and all before the real and nasty stuff actually starts.

The bizarre and increasingly detached excuses from economists and the mainstream media (redundant) is simply that they cannot yet fathom that possibility, but they are starting to as a matter of real economic intrusion into the dominant statistical mirage or fantasy. Six months, half a year, of atrocious, recessionary consumerism should do that: